Fri 11 Dec 2009

Ugh. Day of Finish paper, Take nap, Sleep through Whitman party, Wake up, Post paper late, Go back to bed.

I hate exam week.

Fri 11 Dec 2009

Ugh. Day of Finish paper, Take nap, Sleep through Whitman party, Wake up, Post paper late, Go back to bed.

I hate exam week.

Thu 10 Dec 2009

That’s why he’s using a nom de plume.

First line: “Ten years ago I was permitted to run my hand through the beard of Walt Whitman.”

I thought this article spoke to our class too well to not share it. In case the link doesn’t work, the article is “A Professor and a Pilgrim” by Thomas Benton, published in the Chronicle of Higher Education Vol. 52 issue 49.

<A href=”http://ezproxy.umw.edu:2048/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com.ezproxy.umw.edu:2048/login.aspx?direct=true&db=a9h&AN=21949374&site=ehost-live”>A Professor and a Pilgrim.</A>

Tue 17 Nov 2009

In which I read Whitman’s poem “To You” at Chatham house (formerly Lacy House).

Please enable Javascript and Flash to view this Flash video.

Wed 4 Nov 2009

***These are just notes at the moment. They will be clarified later. For questions, jgroom@umw.edu or arush@umw.edu. Thanks to Andy Rush for the very helpful tutorial!

Vista or 7, you can use the newest version of movie maker – gives the ability to upload directly to youtube.

Secure it from windows live movie maker.

Can use Adobe premier elements, but it isn’t installed in combs 3rd floor lab.

Save files as WMV (windows media video file)

1. Plan video

2. Capture video (or import video from somewhere) – if we have 7 and new version, can import mp4, but otherwise have to convert to another format.

3. Edit it

4. Finish

Import lots of files at once, so that we can deal with them all together.

Might want to view (along the bottom) in Timeline instead of Storyboard)

Transition from clips: don’t use many of the transitions, because they are not what real people use. The only transition which is used is the dissolve (which in moviemaker is called fade). To use, drag effect to its place on the storyboard/timeline.

Video effects: use with discretion, drag to place.

For audio effects: can mute the audio track that went with it. Can then record some voiceovers using “narrate timeline” which comes down from the tab. Or import another audio file, a song or suchlike using the import (mpeg-4 doesn’t seem to work, but others should)

Titles: Titles and Credits: use as desired, some variety in choices.

Save/ publish to computer: want to keep the amount to under 1GB and 10 minutes

PS menus are different in the newer version of moviemaker, so for us vista and 7 users, saving as “Windows Media DVD Quality (3.0 Mbps)” is fine.

There are issues with frame accuracy in the older version of movie maker.

**Conversion from useless video file formats. Use Squared 5. Open file. Export as AVI. Compression: use Apple DV/DVCPRO – NTSC

Mon 2 Nov 2009

So many things struck me about the 1855 to 1891-92 Song of Myself that it is hard to know where to start. I guess at the beginning is always good. Whitman makes a point of saying in the 1891-92 version that he is “now thirty-seven years old in perfect health”. Really, Whitman? If “deathbed edition” means anything, you are neither 37 nor in perfect health. And this line does not appear until the 1881 edition, along with the stanza that it appears in, as well as the following stanza. It is interesting that Whitman is trying to insist upon his youth in his old age. Why such emphasis on him being “now” 37? Does he think that he knows his thirty-seven-year-old self better now than he did then? This strikes me as an extra odd revision, when compared to the others. While they show how his purposes in writing and publishing “Song of Myself” have changed, this one shows how he wishes to make us believe that the poem has stayed the same. (or perhaps that at least he has not aged)

In the end of section three, the 1855 version identifies the “hugging and loving bed-fellow” as God, but he remains unidentified in the deathbed edition. This seems to have two possible explanations: either Whitman’s feelings about God have changed to make the bed-fellow a fellow human being or a secretive God (per his sneaking out of the house at the break of dawn – God’s walk of shame?) or else Whitman simply felt that he need not outright identify the bed-fellow as God, and that he felt the meaning unchanged by the revision. I feel that dropping “God” from this section is important, inasmuch as I would not have considered the bed-fellow as God without it.

On a related note, Whitman shifts his perspective on God at the end of the fifth section. Previously, God was identified as “elder” – the “elderhand of my own”, “the spirit of God is the eldest brother of my own” – in the 1891 edition, God and Whitman are equals, or at least neither is directly placed above the other. Instead, Whitman seems to be embracing more fully his comfortable lack of concern over God. The section about God’s remembrances is still much as it was. This section seems to explain his stance on God that he has adjusted in these other sections. Basically, he says “God is there, He will always be there, and we needn’t worry about Him leaving us.”

To look at the poems fairly, I think that I am actually surprised by how little is changed from the 1855 version to his 1891 version. There probably are not many poets/authors who could constantly revise their works and yet keep so close to the original vision. My artist sister has ruined a few works by revising them over and over again until they don’t resemble anything, much less the pictures that they were originally. It is impressive that Whitman manages to avoid this, even with his numerous reinventions of “Song of Myself”.

Tue 27 Oct 2009

The love that Walt Whitman felt towards Abraham Lincoln can be divided into two broad kinds of love. The first is a personal infatuation bordering on obsession that could alternately be viewed as romantic, but strictly abstract, similar to the feelings of the devotees to Elijah Wood that roamed the halls of my school after The Fellowship of the Ring came out (I know, really? Ian McKellan is totally the hot one of the bunch). This is the Whitman that we lovingly mock, the Whitman who stood on street corners, trying to make eye contact with Lincoln. The other sort of Whitman loved Lincoln because he recognized in him his own (Whitman’s) poetry and philosophy, converted into a working political method. A particularly telling moment is Whitman’s essay, quoted in our Whitman and Lincoln reading, is Whitman’s call for a new, Western-raised president, that Lincoln fulfills unnervingly well. Whitman saw the parallels between his work and that of Lincoln and embraced the political figure of Lincoln. The assassination forced Whitman to reevaluate his feelings on Lincoln, of which the ideologically driven love proved stronger than the mere personal appreciation. Whitman’s lecture on Lincoln and his elegy, “When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom’d”, show his fusion of the two loves and his emphasis on the national persona of Lincoln.

I gather from reading the text of Whitman’s Lincoln lecture and from the dramatic reenactment by Epstein that Whitman felt that Lincoln’s death was a national tragedy, a grief that belonged to all Americans. His appropriation of Peter Doyle’s memories of the assassination is part of Whitman’s belief in the universality of the moment: in a way, everyone experienced what occured that night. While we may not ethically agree with the way he expressed this, it does prove his point. As he appropriates someone else’s experiences of the event, he relives it for the audience, so that they can feel that they were there as well.

On the other hand, “When Lilacs last in the Dooryard Bloom’d” takes the death of Lincoln from a single death and equates it with the other deaths of the war, and death in general. In this way, he identifies his personal grief at the death of Lincoln as the universally experienced grief at the death of loved ones.

Wed 21 Oct 2009

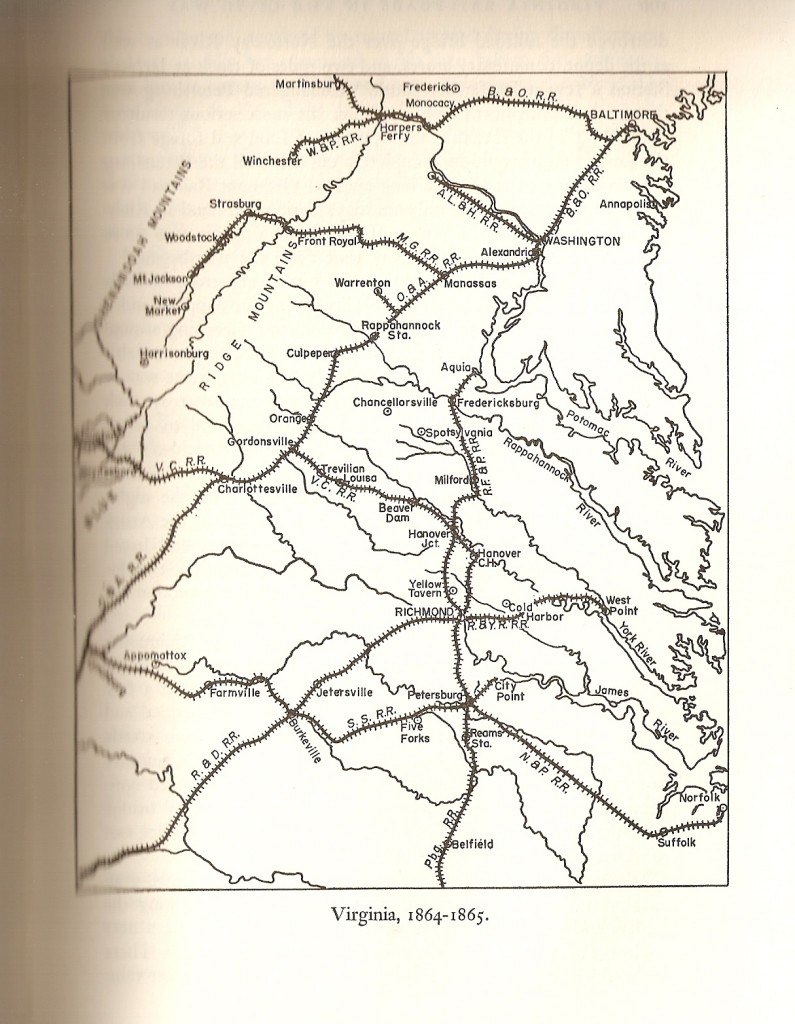

Note the RF&P railroad on the right side.

When Walt Whitman came down to Fredericksburg in 1862, he traveled along a variety of different transportation methods including trains. Trains were a major factor in American travel before the Civil War and they would become invaluable to the war effort in the North and South. The railroads of Virginia were especially important to the outcome of the war, because of their location in a battleground state. The railway of the Richmond, Fredericksburg, and Potomac company was used by both the Confederate and the Union armies throughout the war. Its destruction and reconstruction was especially pivotal to the battle of Fredericksburg which drew Whitman down to Virginia and D.C.

The Richmond, Fredericksburg, and Potomac railway company was chartered in 1834 and had track laid between Richmond and Fredericksburg by 1837. In 1842, the rail ran all the way to Aquia Creek, where a large wharf was built for the steamboats that provided transportation for the remainder of the journey to and from D.C. This is the state that the RF&P railroad was in when war broke out. In 1862, the Confederates retreated across the Rappahannock to Fredericksburg, abandoning approximately 13 miles of track, the wharves, and three bridges. To prevent the Union troops from using this stretch of railroad, the bridges and wharves were demolished, and the track was destroyed.

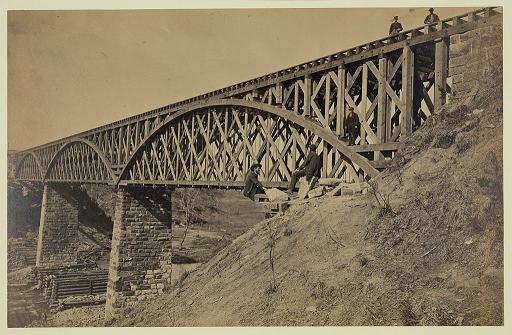

Herman Haupt, from a truly enormous wikipedia image

The same year, Herman Haupt, who wasthe commander of the construction corps of the new United States Military Railroad, was charged with rebuilding the railroad up to the Rappahannock for transportation of troops and supplies. With only a few small troops of untrained laborers, handtools, and limited supplies, Haupt rebuilt the wharves, the track and two of the bridges in a matter of weeks. The most impressive piece of this achievement was the bridge across Potomac Creek which needed to be over 400 feet long and 80 feet high and had originally been built by the RF&P co. over the course of a year. Haupt and his men had a bridge up in nine days and trains crossing it a few days after that. The bridge was built in an unconventional fashion using poles cut from the surrounding woods; however, it was sturdy enough for the job. After crossing the the bridge, Lincoln remarked that “upon my word, gentlemen, there is nothing in it but beanpoles and cornstalks” (Griffin 12). In August 1862, the Union army was moving northwards again and General Burnside, not yet commander of the army, ordered the destruction of the bridge. Haupt was understandably upset to see his work destroyed.

"...nothing in it but beanpoles and cornstalks" Abraham Lincoln

In a few months, however, he would have the opportunity to rebuild it. Burnside, now in command of the army, began assembling his men across the Rappahannock by Fredericksburg and once again the wharves, track and bridges had to be rebuilt or repaired to furnish the men with supplies and to offer transportation. This time, the bridge at Potomac Creek was built mainly with prefabricated pieces and remained in place through the battle. Although the railroad was in working order amazingly soon after the repairs began, they still took sometime to complete and this in part contributed to the Confederates’ readiness for the battle when it occurred.

Potomac Creek Bridge, taken on April 18, 1863 by Andrew J. Russell

This would have been the railroad that Whitman rode on to reach his brother in Fredericksburg. He would have ridden by steamboat down from D.C. to Aquia Creek landing and from there, he likely traveled the thirteen miles by train to the banks of the Rappahannock. When he was returning, he would have retraced his steps, although this time in the company of the many sick, wounded, and dying men that were also being transported up to D.C.

Ironically, the same railroad that assisted the Union army at the battle of Fredericksburg was simultaneously assisting the Confederate army. The track still ran south of Fredericksburg to Richmond and was invaluable for transportation of troops, supplies, and information. The trains were so invaluable that Lee ordered that the trains were not to enter Fredericksburg itself, for fear of attack by Union soldiers across the river, but that they should halt at Hamilton’s Crossing about four miles south of Fredericksburg. This was largely due to the increasing scarcity of locomotives and railcars in the south, where proper materials could not be found to repair or build new ones. To further hinder the Union forces in case of Confederate defeat at Fredericksburg, the track between Hamilton’s Crossing and Fredericksburg was torn up just before the battle, truly making the end of the line for the southern section of the RF&P railroad at Hamilton’s Crossing. The battle of Fredericksburg was an unpleasant intimation to Lee of scarcity that he and his men would face in the coming years, not just with locomotives, but with almost any necessity.

In the following winter, the rail services would suffer from undue demands put on them by the military as well as the ordinary citizens of Virginia. Wood especially was scarce, with the demand for firewood in soldier camps as well as in the cities for heat confronting the railroads’ own demands for wood for the boilers and repair of the railroad ties. This was aggravated by theft by undisciplined soldiers or civilians of both the railroad’s firewood and occasionally the railroad ties themselves.

While the southern section of the RF&P railroad remained mostly active for the remainder of the war, despite lack of materials, the section north of the Rappahannock was to be burned and rebuilt one more time, in 1864, when it was used to move wounded soldiers from the battles of the Wilderness and Spotsylvania Court House.

Otherwise, the railroad was used for private use through the war, including an increasingly lucrative contraband business across the Rappahannock. The main items of interest were tobacco and coffee, one lacking in the North, the other lacking in the South. In 1865, Grant decided to end the contraband trade in hopes of hastening the end of the war and captured a train full of tobacco and other supplies heading for Fredericksburg. The contraband was burned. Afterward, a systematic search was made of Fredericksburg houses for more contraband tobacco which was confiscated and burned as well. This ended the contraband trading through Fredericksburg during the war.

Mon 19 Oct 2009

I’m having trouble reconciling Whitman’s desire to portray the war honestly and his poems that are set in the midst of battle. I suppose it is a naïve assumption, but, before Drum-Taps, I felt that the voice in Whitman’s poetry was his own. In Drum-Taps, however, this is obviously not the case, as Whitman never truly experienced some of the situations in his poems, all the various battlefield scenes. Why did he place his experiences and insights that he acquired in the hospital on a battlefield that he was never on?

Drum-Taps is notable for the shift in Whitman’s attention span, for lack of a better word. In his earlier poems, especially the 1855 “Song of Myself”, he is in a hurry to encompass everything in his poems and because of this, some detail must be lost. So he lists everywhere and everyone, but he does not make each one notable. These Civil War poems are more contemplative in that they focus on one item at a time, devoting the poet and the reader to the observation of a single incident. This would seem to be a talent that Whitman would have developed sitting long hours at a hospital.

I think that Whitman came to respect the strength of the individual soldiers that he came across in the hospital. By placing his poems in the mouths of soldiers much like the ones he met, he is showing them his respect and love. His purpose in the hospital was similarly self-sacrificing. He could not demand anything of the wounded, but gave what he could to them instead. In this way, he could not continue in the same style as he had before. While the war strengthened his resolve in some areas, as in the area of brotherly love, his confidence in one work’s ability to contain everything and treat all the material within it respectfully was waning. This is evident in his slapdash 1867 Leaves of Grass, where the bizarre binding expresses his own anxiety over his encyclopedic work in which he had placed such faith before the war. The construction of Drum-Taps may seem to contradict this with its careful evolution from naïve patriot through the battles and hospitals to the wise and still energetic leader that we find at the end of the book. However, Whitman is not changed completely by the war; he just finds it more important to devote himself to these voices that would otherwise be lost. The idea that poetry can be a higher means of communicating and creating community is just as important to Whitman during the war, and after it, as it was to him before the war.

I suppose Whitman felt his hospital work was important for himself and for the soldiers, but for America, the soldiers were the first heroes and even they are not properly understood by Americans at large. Therefore, Whitman must subsume his own desire to be recognized for his hospital work to show America the soldiers that would otherwise be unnamed and unknown.

Tue 6 Oct 2009

Just for fun, I thought I’d post this, a comic, not about Whitman, but James Joyce….

Thanks to Kate Beaton, Hark A Vagrant!

Tue 6 Oct 2009

In my first readthrough of Drum-Taps, I noticed numerous poems using the image of the moon so I thought I’d go back through with an eye on nighttime in Drum-Taps. The first poems in the cycle, notably “First O Songs for a Prelude” and, obviously, “Song of the Banner at Daybreak”, are set at daybreak. The voice of the Banner even says “out of the night emerging for good” (425).

In “Bivouac on a Mountain Side”, Whitman turns his attention to the night: “And over all the sky—the sky! far, far out of reach, studded, breaking out, the eternal stars” (435). This, however, seems to be part of a mini-poetic-cycle about the soldiers’ days and nights, alternating for four short poems: “Calvalry Crossing a Ford”, “Bivouac on a Mountain Side”, “An Army Corps on the March”, and “By the Bivouac’s Fitful Flame”. The last poem brings in the notion that nighttime is when one reflects on death and memories, a notion with which Whitman ends the next poem “Come Up From The Fields Father”: “In the midnight waking, weeping, longing with one deep longing,/O that she might withdraw unnoticed, silent from life escape and withdraw,/ To follow, to seek, to be with her dear dead son” (438). He then immerses a poem entirely in night, “Vigil Strange I Kept On the Field One Night”, a soldier keeping wake for a younger soldier (with Whitman, I am loathe to take the mention of “father” and “son” too literally), not grieving necessarily but tenderly remembering, until a dawn burial. “A March in the Ranks Hard-Prest, and the Road Unknown” depicts a nighttime hospital set up in a church with little light.

The moon makes its first appearence in “Dirge for Two Veterans”. The speaker calls it “silvery” “beautiful” “ghastly” “immense”, a “sorrowful vast phantom”, “some mother’s large transparent face”. Now the full moon is linked with the tenderness of nighttime grief and burial. “Look Down Fair Moon” adds a sense that the moon’s light hallows the dead bodies on the fields. This is echoed in “Reconciliation” in which the moon is seen as the sister of Death, and together they wash “this soil’d world” (453). “Lo Victress on the Peaks” has Whitman distancing himself from the glory-mongering attitude of his earlier poems, offering up his poems of “night’s darkness and blood-dripping wounds,/And psalms of the dead” (455)

The final poem of Drum-Taps, fittingly enough, brings the cycle back into daylight with the return of “forenoon air” and the final line “But the hot sun of the South is to fully ripen my songs” (458).

While this progression from daybreak to hot sun to cool night to day again may be an expression of the Civil War as a descent into blackness, a nightmare, etc., I feel that nighttime and the Civil War do not correspond exactly. I think rather that the connection is between night and death/memory. Whitman seemed a daytime poet before these writings, all his poems taking place in full day and bright sun. With his hospital visits and understanding of war and death which that gave him, Whitman develops a new appreciation for the solitude of nighttime and the power of the emotions he saw felt by dying soldiers in the night and felt himself for dead comrades. Nighttime makes it easy for Whitman’s tender and compassionate poet to emerge.