Fri 11 Dec 2009

Ugh. Day of Finish paper, Take nap, Sleep through Whitman party, Wake up, Post paper late, Go back to bed.

I hate exam week.

Fri 11 Dec 2009

Ugh. Day of Finish paper, Take nap, Sleep through Whitman party, Wake up, Post paper late, Go back to bed.

I hate exam week.

Thu 10 Dec 2009

That’s why he’s using a nom de plume.

First line: “Ten years ago I was permitted to run my hand through the beard of Walt Whitman.”

I thought this article spoke to our class too well to not share it. In case the link doesn’t work, the article is “A Professor and a Pilgrim” by Thomas Benton, published in the Chronicle of Higher Education Vol. 52 issue 49.

<A href=”http://ezproxy.umw.edu:2048/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com.ezproxy.umw.edu:2048/login.aspx?direct=true&db=a9h&AN=21949374&site=ehost-live”>A Professor and a Pilgrim.</A>

Tue 17 Nov 2009

In which I read Whitman’s poem “To You” at Chatham house (formerly Lacy House).

Please enable Javascript and Flash to view this Flash video.

Wed 21 Oct 2009

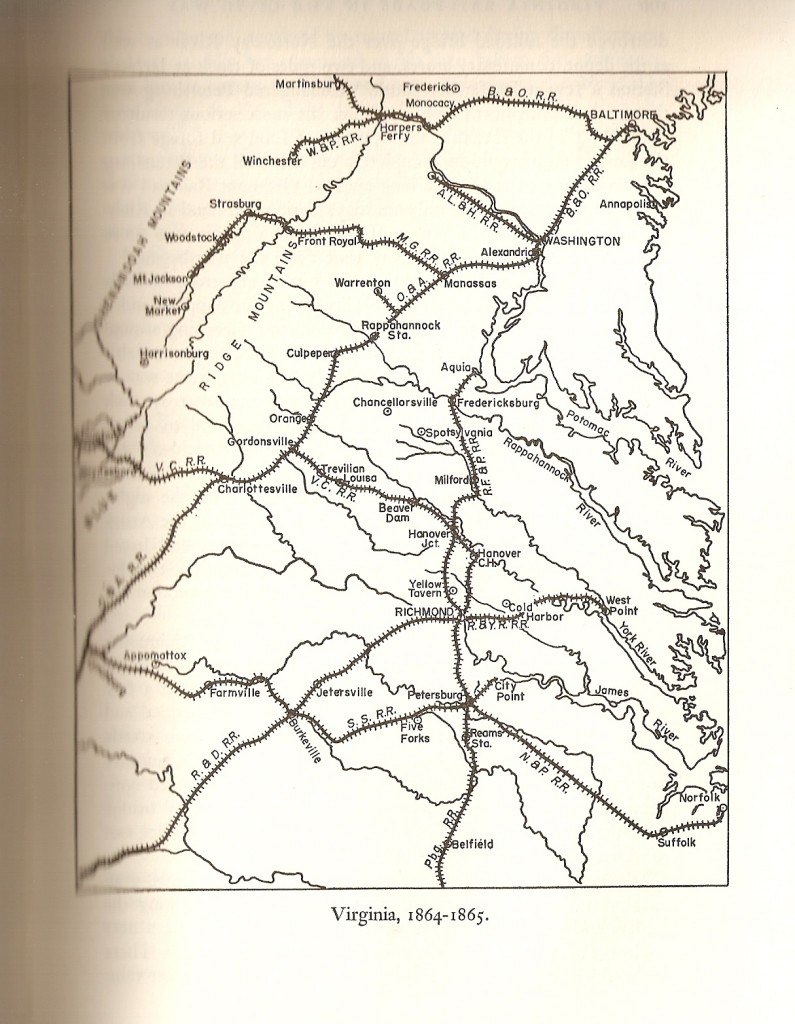

Note the RF&P railroad on the right side.

When Walt Whitman came down to Fredericksburg in 1862, he traveled along a variety of different transportation methods including trains. Trains were a major factor in American travel before the Civil War and they would become invaluable to the war effort in the North and South. The railroads of Virginia were especially important to the outcome of the war, because of their location in a battleground state. The railway of the Richmond, Fredericksburg, and Potomac company was used by both the Confederate and the Union armies throughout the war. Its destruction and reconstruction was especially pivotal to the battle of Fredericksburg which drew Whitman down to Virginia and D.C.

The Richmond, Fredericksburg, and Potomac railway company was chartered in 1834 and had track laid between Richmond and Fredericksburg by 1837. In 1842, the rail ran all the way to Aquia Creek, where a large wharf was built for the steamboats that provided transportation for the remainder of the journey to and from D.C. This is the state that the RF&P railroad was in when war broke out. In 1862, the Confederates retreated across the Rappahannock to Fredericksburg, abandoning approximately 13 miles of track, the wharves, and three bridges. To prevent the Union troops from using this stretch of railroad, the bridges and wharves were demolished, and the track was destroyed.

Herman Haupt, from a truly enormous wikipedia image

The same year, Herman Haupt, who wasthe commander of the construction corps of the new United States Military Railroad, was charged with rebuilding the railroad up to the Rappahannock for transportation of troops and supplies. With only a few small troops of untrained laborers, handtools, and limited supplies, Haupt rebuilt the wharves, the track and two of the bridges in a matter of weeks. The most impressive piece of this achievement was the bridge across Potomac Creek which needed to be over 400 feet long and 80 feet high and had originally been built by the RF&P co. over the course of a year. Haupt and his men had a bridge up in nine days and trains crossing it a few days after that. The bridge was built in an unconventional fashion using poles cut from the surrounding woods; however, it was sturdy enough for the job. After crossing the the bridge, Lincoln remarked that “upon my word, gentlemen, there is nothing in it but beanpoles and cornstalks” (Griffin 12). In August 1862, the Union army was moving northwards again and General Burnside, not yet commander of the army, ordered the destruction of the bridge. Haupt was understandably upset to see his work destroyed.

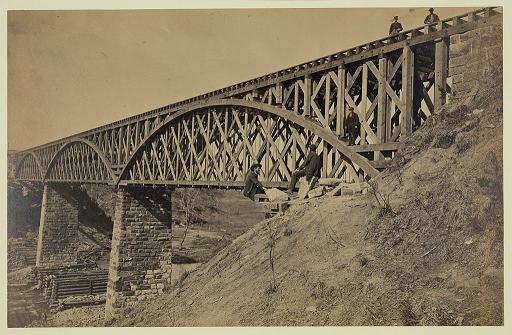

"...nothing in it but beanpoles and cornstalks" Abraham Lincoln

In a few months, however, he would have the opportunity to rebuild it. Burnside, now in command of the army, began assembling his men across the Rappahannock by Fredericksburg and once again the wharves, track and bridges had to be rebuilt or repaired to furnish the men with supplies and to offer transportation. This time, the bridge at Potomac Creek was built mainly with prefabricated pieces and remained in place through the battle. Although the railroad was in working order amazingly soon after the repairs began, they still took sometime to complete and this in part contributed to the Confederates’ readiness for the battle when it occurred.

Potomac Creek Bridge, taken on April 18, 1863 by Andrew J. Russell

This would have been the railroad that Whitman rode on to reach his brother in Fredericksburg. He would have ridden by steamboat down from D.C. to Aquia Creek landing and from there, he likely traveled the thirteen miles by train to the banks of the Rappahannock. When he was returning, he would have retraced his steps, although this time in the company of the many sick, wounded, and dying men that were also being transported up to D.C.

Ironically, the same railroad that assisted the Union army at the battle of Fredericksburg was simultaneously assisting the Confederate army. The track still ran south of Fredericksburg to Richmond and was invaluable for transportation of troops, supplies, and information. The trains were so invaluable that Lee ordered that the trains were not to enter Fredericksburg itself, for fear of attack by Union soldiers across the river, but that they should halt at Hamilton’s Crossing about four miles south of Fredericksburg. This was largely due to the increasing scarcity of locomotives and railcars in the south, where proper materials could not be found to repair or build new ones. To further hinder the Union forces in case of Confederate defeat at Fredericksburg, the track between Hamilton’s Crossing and Fredericksburg was torn up just before the battle, truly making the end of the line for the southern section of the RF&P railroad at Hamilton’s Crossing. The battle of Fredericksburg was an unpleasant intimation to Lee of scarcity that he and his men would face in the coming years, not just with locomotives, but with almost any necessity.

In the following winter, the rail services would suffer from undue demands put on them by the military as well as the ordinary citizens of Virginia. Wood especially was scarce, with the demand for firewood in soldier camps as well as in the cities for heat confronting the railroads’ own demands for wood for the boilers and repair of the railroad ties. This was aggravated by theft by undisciplined soldiers or civilians of both the railroad’s firewood and occasionally the railroad ties themselves.

While the southern section of the RF&P railroad remained mostly active for the remainder of the war, despite lack of materials, the section north of the Rappahannock was to be burned and rebuilt one more time, in 1864, when it was used to move wounded soldiers from the battles of the Wilderness and Spotsylvania Court House.

Otherwise, the railroad was used for private use through the war, including an increasingly lucrative contraband business across the Rappahannock. The main items of interest were tobacco and coffee, one lacking in the North, the other lacking in the South. In 1865, Grant decided to end the contraband trade in hopes of hastening the end of the war and captured a train full of tobacco and other supplies heading for Fredericksburg. The contraband was burned. Afterward, a systematic search was made of Fredericksburg houses for more contraband tobacco which was confiscated and burned as well. This ended the contraband trading through Fredericksburg during the war.

Tue 6 Oct 2009

Just for fun, I thought I’d post this, a comic, not about Whitman, but James Joyce….

Thanks to Kate Beaton, Hark A Vagrant!

Tue 1 Sep 2009

Sit awhile wayfarer,

Here are biscuits to eat and here is milk to drink,

But as soon as you sleep and renew yourself in sweet clothes

I will certainly kiss you with my goodbye kiss and open

the gate for your egress hence.

Long enough have you dreamed contemptible dream,

Now I wash the gum from your eyes,

You must habit yourself to the dazzle of the light and of

every moment of your life

(83)

To me, Whitman’s portrait is the visual counterpart to his poems. Therefore, he appears to me in a confident stance that invites conversation. He is intent on the reader and is paying close if somewhat insolent attention to the viewer. His casual clothes and the full body image set him apart from the other poets that he tries to set himself apart from in his poems as well.

I am not Walt Whitman, so I do not feel that it would be appropriate for me to try to convey the same message as his image does. Instead, I feel this corresponds nicely to the selection from his poem. He tells the reader that he wants to welcome him, teach him to see and experience life, then send him on his way to continue experiencing things. This is me, enjoying “the dazzle of” that moment of my life.

Sun 30 Aug 2009

In the preface to the 1855 edition to Leaves of Grass, Whitman tells of the master poet. The qualities this poet is to have are numerous: American, embodying the American spirit, not slave to rhyme and meter, not veiling his poems in obscure language, etc. Is Whitman here speaking of what his work as a poet is to be or is he describing an ideal that he will strive to reach without expectation of success? To me, this preface does not describe what Whitman thinks his own poetry is to be. I believe that all the qualities he describes and the relationships between poet and non-poets are part of a great ideal that he himself wishes to measure himself against and strive for.

At the end of the preface, Whitman says “The proof of a poet is that his country absorbs him as affectionately as he has absorbed it.” And America, as Whitman points out, is such a massive space, with so much that must be absorbed, that the task seems near impossible. Although he lists many things (for example, his listing of rivers on page 7), he is showing the enormous span that America has and conveying that even these lists only touch on the wonders of America.

The poet, says Whitman, is to be modest, but possessing of great powers. “In war he is the most deadly force of the war” (9). “The greatest poet hardly knows pettiness or triviality” (10). These and others build the vision of the great poet to dizzying heights of perfection. This great poet must not only know and sing of his country but be “complete lover” to the whole universe (11). Whitman distances himself from this identity by keeping this unnamed great poet at third person.

Despite the arm’s length at which he tries to keep his description of “the great poet”, Whitman is also listing qualities that he has decided to embody, especially those pertaining to writing and composing poems. His subject matter is the width and breadth of the American experience. He does sport simplicity, as his great poet claims “I will have nothing hang in the way, not the richest curtains”(14). He does not use “rhyme or uniformity or abstract addresses to things nor…melancholy complaints or good precepts” (11).

This preface seems to be presenting the reader with the criteria with which Whitman would like the works following to be judged. “This,” he seems to say, “is what I am striving for, not the traditional style of European poetry, or poetry in general.”While I don’t yet know (not having read much of Whitman’s body of works) to what extent he succeeds at all his lofty aims mentioned in the preface, I believe that they are definitely what I should keep in mind when reading his poems, even the later ones where his aims may have evolved.

Tue 25 Aug 2009

Here I am, everyone!

Not that this helps with identification, but here's me as George Washington.

Looking forward to tracking Walt Whitman this semester!