The tour of Ft. Greene Park led by Greg Trupiano was not only informative but inspirational. I left the tour with a much greater understanding of Ft. Greene because of the information presented. The tour began at the visitor’s center in Ft. Greene Park and Greg began to present the history and relevance of Whitman to this park. What was especially pleasing was that Greg brought along a gentleman who read selections of Whitman with great presence. It is always great to hear Whitman spoken aloud, as I believe he wrote it to be spoken aloud. In addition there was in attendance a member of the conservatory, Charles, who had quite a bit to contribute about the park. During the presentation Nicole sang Whitman’s words. She is a professional Opera singer. Her voice resonatedwithin me long after the tour had ended. The fourth person in attendance was an expert on Crown Heights and Bed-Stuy. She was also able to contribute her knowledge to the experience. The prison ship martyr’s monument in Ft. Greene Park is over the crypt of bones from the prisoners’ ships in the harbor. There is one full set of remains, the of Benjamin Romaine, and the vault can only be opened by the great great great great granddaughter of Benjamin Romaine, Vicki Romaine. There are lots of other bones in the crypt, but none as complete. They washed up on the shores of the old Navy Yard, and in the morning the prisoners ships would turn over thir dead and they would be buried in shallow graves where the old Navy Yard is today. The water would uncover the bones and the remains were collected for this crypt. There was lots of talk of the Old Jersey. Whitman writes in New York, “the principal of these prison ships was the old Jersey, a large 74-gun …the one which seems to have been most relied on was the old Jersey. The British took a great manyAmerican prisoners during the war-not only by land, but also by their privateers, at sea. When a capture was made in any of the waters near enough, the prisoners were brought with the vessel to New York. These helped to swell the rank of the unhappy men, who were crowded together in the most infernal quarters, starved, diseased, helpless, and many becoming utterly desperate and insane.-Death and starvation killed them off rapidly” (31). More men died on these ships than died in the entire Battle of Brooklyn. When word got back to Great Britain about these deaths it brought a lot of shame on the soldiers. The anonymity between American and Great Britain remained up until the first World War. After the great presentation at the crypt, we moved on to Whitman’s only standing residence in Brooklyn, 99 Ryerson Street. We gathered across the street and had a question and answer exchange. It is our understanding that everybody who lives in their is quite aware that this is Whitman’s house. Many of the tennants have been students of Pratt. Then we walked back towards CUNY as a group. It was a beautiful day for a tour, and we all left more inspired than we had arrived three hours earlier.Please enable Javascript and Flash to view this Flash video.

Archive for November, 2009

Chuck For Dec. 2nd

Sunday, November 29th, 2009Where Chuck Found Whitman

Tuesday, November 24th, 2009Please enable Javascript and Flash to view this Flash video.

Chuck for Nov. 17th

Monday, November 23rd, 2009Franklin Evans of The Inebriate: A Tale of the Times. I found the story to be quite dark as has been very often my feelings throughout this course. It is a tale or warning against the use and abuse of alcohol. What I found missing was the lack of mention of other vices in a large city that can lead a farm boy astray. It focused only on alcohol. Whitman’s story of a boy raised out of Long Island who comes to the Big City to stake his claim is often troubling. We follow the young lad through his trials and tribulations with alcohol from his first drink with his buddy Colby to his sobriety with the Temperance movement. Along this journey there was many a grim tale of death, destitution, poor judgement, and the loss of one’s character. The tales at the beginning of the novel were about others. The first spoke of a hale and hearty farmer and his children growing up around him, “Unfortunately, he fell into habits of intemperance. Season after season passed away; and each one, as it came, found him a poorer man than that just before it. Everything seemed to go wrong. He attributed it to ill luck, and to the crops being injured by unfavorable weather. But his neighbors found no more harm from these causes than in the years previous, when the tippler was as fortunate as any of them. The truth is, that habits of drunkenness in the head of a family, are line an evil influence…” (6-7). As they proceeded along their journey a tale was told of alcohol amongst the Native Americans, “‘The greatest curse,’ said he, growing warm with his subject—’the greatest curse ever introduced among them, has been the curse of rum! I can conceive of no more awful and horrible, and at the same time more effective lesson, than that which may be learned from the consequences of the burning firewater upon the habits and happiness of the poor Indians. A whole people – the inhabitants of a mighty continent – are crushed by it, and debased into a condition lower than the beast of the field. Is it not a pitiful thought? The bravest warriors—the wise old chiefs—even women and children—tempted by our people to drink this fatal poison, until, as year and year passed away, they found themselves deprived not only of their lands and what property they hitherto owned, but of everything that made them noble and grand as a nation! Rum has done great evil in the world, but hardly ever more by wholesale than in the case of the American savage.'” (10). I found myself lost by the tale of the Indians as the talk of alcohol left the dialogue and turned to a story of revenge, thereby not only not fitting in with the Native American tale of temperance but the entire book. Upon arrival in New York the story lends itself to Franklin Evans’ own experiences and observations. Colby, who traveled from the country with Franklin Evans, introduced Franklin Evans to the drinking scene, “Those beautiful women-warbling melodies sweeter than I ever heard before, and the effect of the liquor upon my brain, seemed to lave me in happiness, as it were, from head to foot!” (27). He began drinking regularly with Colby. He finds employment and eventually loses it dues to the side effects of intemperance. We find Franklin Evans to marry his landlady’s daughter, Mary, and intemperance ate away at their marriage. Mary was of delicate temperament and could not survive the marriage to a drunkard. Whitman writes, “Then came the closing scene of that act of the tragedy. My wife, stricken to the heart, and unable to bear up longer against the accumulating weight of shame and misery, sank into the grave-the innocent victim of another’s drunkenness” (50). Through the horrors of alcohol he found himself embracing the glorious temperance pledge which is defined as nothing stronger than wine. He found himself taking up or participating in a burglary in which he was readily caught and found himself in jail. He was given reprieve due to his association with the Marchion family of which he saved their child from drowning in the past. Mr. Marchion got him off. The Marchion share with him their own tragic experiences with alcohol. They had pledged temperance. He left the city and went to live in the country in Virginia where, although he was not partaking of alcohol stronger than wine, his judgement was still off. He fell in love with a Creole slave, married her, fell out of love with her, fell in love with a Mrs. Conway, “her light hair, blue eyes, and the delicacy of her skin, formed a picture rarely met with in the region” (84), and nothing but jealousy and rage and ultimately death ensued. Franklin Evans headed back to New York. He visited his first employer, Mr. Lee, who was all too familiar with the dangers of alcohol and, understanding Franklin Evans predicaments and battle with intemperance, being in the city without employment, Mr Lee left him upon his death comfortable property. He still visited the Marchions, as he still considered them friends, and shared his stories with them of his time in Virginia and his marriage to the Creole and the death of Mrs. Conway, and they (the Marchions) had moved deeper into the temperance movement (which was a movement of reformers of which only abstinence would suffice). I find the tale a bit of a stretch as I have first hand knowledge of the disease of alcoholism.

Chuck for Nov. 10th

Thursday, November 19th, 2009 The trip to the Brooklyn Historic Society was of great interest to me as I am an avid fan of all things Brooklyn. It came as a surprise to me of its location at the corner of Clinton and Pierpont as I am down in that area quite often and had not realized that such a great resource was so close by. Upon approaching the large red brick building the architecture was overpowering. Its huge windows, red bricks and the large masonry faces near the top of the building were quite impressive. Upon entering the library, it felt as though you were entering history itself. The purpose of the visit was for us to become members and become better acquainted on how to use the resources of the library to work on our final project, Where I Found Whitman Addresses. We first were brought to insurance maps of the 1860’s. My address in particular is 71 Prince St. circa 1840. Through looking at the 1860 Paris Volume I map I found it to be a two story frame house as the maps were color coded, yellow meaning framed, red meaning brick, and other various colors for hospitals, churches, and other institutions. Then I proceeded to the 1886 map to find that the address had changed to 153 Prince Street. I was able to deduct this by comparing the two maps and counting how many lots off the corner the building was. I was also able to secure the old block and lot numbers from this map, block 138 lot 122. This map also provided the wards throughout the city, 153 Prince Street is in Ward 11. Then I proceeded to the 1929 map and found the address remained 153 Prince, and I now have a new block and lot number; block 2063 lot 6. Armed with this information, I intend to visit the tax assessors at 32 Chambers Street and look at the municipal archives. I will also go to 210 Joraleman Street and seek out the Department of Buildings to see what I can find. Elizabeth, the librarian, was very helpful in showing us how to navigate the sea of information. After looking at several of these maps she directed me to the Deed transfers of the time period. I found this part of the research very frustrating as the deed transfers related to the entire square block and the best that could be surmised was which buildings were on Prince Street. There was no indication of addresses or block and lot numbers. I did nevertheless review them and some were more interesting than others as to who owned what and sold to whom. I intend on revisiting this landmark numerous times in the near future to flesh out more information on 71 Prince Street.

The trip to the Brooklyn Historic Society was of great interest to me as I am an avid fan of all things Brooklyn. It came as a surprise to me of its location at the corner of Clinton and Pierpont as I am down in that area quite often and had not realized that such a great resource was so close by. Upon approaching the large red brick building the architecture was overpowering. Its huge windows, red bricks and the large masonry faces near the top of the building were quite impressive. Upon entering the library, it felt as though you were entering history itself. The purpose of the visit was for us to become members and become better acquainted on how to use the resources of the library to work on our final project, Where I Found Whitman Addresses. We first were brought to insurance maps of the 1860’s. My address in particular is 71 Prince St. circa 1840. Through looking at the 1860 Paris Volume I map I found it to be a two story frame house as the maps were color coded, yellow meaning framed, red meaning brick, and other various colors for hospitals, churches, and other institutions. Then I proceeded to the 1886 map to find that the address had changed to 153 Prince Street. I was able to deduct this by comparing the two maps and counting how many lots off the corner the building was. I was also able to secure the old block and lot numbers from this map, block 138 lot 122. This map also provided the wards throughout the city, 153 Prince Street is in Ward 11. Then I proceeded to the 1929 map and found the address remained 153 Prince, and I now have a new block and lot number; block 2063 lot 6. Armed with this information, I intend to visit the tax assessors at 32 Chambers Street and look at the municipal archives. I will also go to 210 Joraleman Street and seek out the Department of Buildings to see what I can find. Elizabeth, the librarian, was very helpful in showing us how to navigate the sea of information. After looking at several of these maps she directed me to the Deed transfers of the time period. I found this part of the research very frustrating as the deed transfers related to the entire square block and the best that could be surmised was which buildings were on Prince Street. There was no indication of addresses or block and lot numbers. I did nevertheless review them and some were more interesting than others as to who owned what and sold to whom. I intend on revisiting this landmark numerous times in the near future to flesh out more information on 71 Prince Street.

The Vault at Pfaff’s

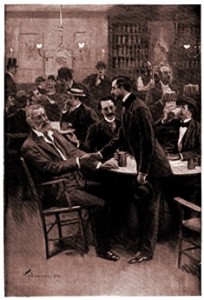

Tuesday, November 17th, 2009 The history of the Vault at Pfaff’s is the history of not only a place, but of the people who frequented its tables. The Vault was opened in 1855 by Charles Ignatious Pfaff, a foreigner with ascetic tastes, on Broadway near the corner of Bleeker Street. Sources disagree as to the exact address of the original Pfaff’s, with one stating it as 689 Broadway (Reynolds 376) and another as 653 Broadway (Miller 89). Regardless of the exact address, Pfaff’s was located in the heart of what was then a cultural hub of New York, Greenwich Village. Pffaf’s was dark and smoky with tables, seats and barrels for sitting on that were scattered around; it was known for its coffee, German beers, cheeses, and a fully stocked wine cellar (Miller 89). This setting attracted the budding Bohemian literary movement of the time. The original Bohemian lifestyle was born in France. Initially it was the necessary lifestyle of the starving artist, but soon it became romanticized into an ideal of shunning the emerging capitalist way of life and embracing art as the greatest truth. This romanticization emigrated to New York and found its home in Greenwich Village. Men were the most frequent visitors at Pfaff’s but, because of progressive ideals of the Bohemian mindset, women with strong characters also became famous frequenters. The Vault at Pfaff’s was so centrifugal to the Bohemian movement in America that the first group of American Bohemians became simply known as “Pfaffians”.

The history of the Vault at Pfaff’s is the history of not only a place, but of the people who frequented its tables. The Vault was opened in 1855 by Charles Ignatious Pfaff, a foreigner with ascetic tastes, on Broadway near the corner of Bleeker Street. Sources disagree as to the exact address of the original Pfaff’s, with one stating it as 689 Broadway (Reynolds 376) and another as 653 Broadway (Miller 89). Regardless of the exact address, Pfaff’s was located in the heart of what was then a cultural hub of New York, Greenwich Village. Pffaf’s was dark and smoky with tables, seats and barrels for sitting on that were scattered around; it was known for its coffee, German beers, cheeses, and a fully stocked wine cellar (Miller 89). This setting attracted the budding Bohemian literary movement of the time. The original Bohemian lifestyle was born in France. Initially it was the necessary lifestyle of the starving artist, but soon it became romanticized into an ideal of shunning the emerging capitalist way of life and embracing art as the greatest truth. This romanticization emigrated to New York and found its home in Greenwich Village. Men were the most frequent visitors at Pfaff’s but, because of progressive ideals of the Bohemian mindset, women with strong characters also became famous frequenters. The Vault at Pfaff’s was so centrifugal to the Bohemian movement in America that the first group of American Bohemians became simply known as “Pfaffians”.

Pfaff’s was the perfect place for writers and literary types to come and drink while sharing their writings and opinions of other writers. Patrons were known to stand and recite their new works before having them published. Some of the most famous patrons of Pfaff’s were, “Ada Clare, the Queen of Bohemia…the actress Adah Isaacs Menken…the fictionist Fitz-James O’Brien…(author) Fitz-Hugh Ludlow…Artemus Ward, the comedian…the picturesque poet N.G. Shephard and the Poesque tale writer Charles D. Gardette” (Reynolds 377). Perhaps the most famous patrons of all were Walt Whitman and Henry Clapp Jr., the King of the Bohemians. Clapp was born in Nantucket but spent many years in Paris. His writing was considered controversial and his most controversial move of all was creating the Saturday Press. Miller writes that the Saturday Press was a, “mix of radical politics, personal freedom, naïveté, silliness, realism, sexual frankness, and exuberance…” (89). The Press allowed Clapp to publish his views and to also highlight the works of authors that he appreciated. One of these authors was Walt Whitman and his works “Out of the Cradle Endlessly Rocking” and “O Captain! My Captain!” among dozens of other items. Unfortunately the Press was plagued with financial troubles and only existed for a year before it had to be shut down. Clapp was not to give up without a fight. Purely through strength of will Clapp reopened the Press in 1865 for two weeks, just long enough to publish “Oh Captain! My Captain!” and “The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County” which catapulted Mark Twain to fame. Clapp, as the King of Bohemia, sat at the head of the table at Pfaff’s while Whitman usually took his place to the side at a separate table.

Although Whitman was touted as the “reigning luminary” (Burrows & Wallace 711) Whitman did not come to Pfaff’s to be the center of attention. As he himself stated, “My own greatest pleasure at Pfaff’s was to look on – to see, talk little, absorb. I was never a great discusser, anyway”. This is not to say that Whitman was entirely silent, he was known to read new works aloud as well as to become embroiled in tiffs with other writers. Whitman wrote of Thomas Bailey Aldrich’s The Bells, “Yes, Tom, I like your tinkles: I like them very well” (Parry 41). He also made a short term enemy with George Arnold. Parry writes that George Arnold one night made the mistake of toasting the South. Whitman, a proud Yankee, jumped up and gave a long patriotic speech (quite unlike his placid Pfaffian demeanor) to which Arnold responded with a tug on Whitman’s beard (42). Quarrels were to be expected because of the very nature of Pfaff’s; it was a place that encouraged drinking and liberal speech simultaneously.

Liberality reigned supreme in many forms. An important aspect of Pfaff’s was its female presence. Ada Claire was far and beyond the Queen. She was the trail blazer for all women who were to eventually find company at Pfaff’s, but she was also the woman to stay the longest. Ada was considered by Whitman to be born ahead of her time (Parry 14). Although she wrote love poems, she was really famous for her utter disregard of social norms. Ada Claire flaunted her love affairs and her illegitimate child born of one such affair, she smoked and drank with the Pfaffian men, and she took to the stage in order to achieve fame (Miller 91-92). Alongside Claire was Adah Isaacs Menken, known as, “a writer and actress and heroine of celebrated off-stage adventures” (Kaplan 243). Like Claire, Menken’s life was full of romantic drama and an illegitimate child. But unlike Claire, Menken found more success on stage when she stared in Mazeppa a play in which she was strapped to a horse practically naked. Adah Isaacs Menken was a great fan of Whitman and aligned him with Edgar Allen Poe, the Patron saint of the Pfaffians.

Poe came to rule over the Pfaffian crowd for obvious reasons. For one, he was a maligned writer who was unappreciated in his time. For two, the Pfaffians related well with Poe’s melancholic nature, no doubt enhanced for them by their drinking. In their own way, many of the Pfaffians emulated Poe. Whitman himself went down the melancholic road when he wrote in Two Vaults, “The Vault at Pfaff’s where the drinkers and laughers meet to eat and drink and carouse, While on the walk immediately overhead pass the myriad feet of Broadway As the dead in their graves are underfoot hidden”. Fitz-James O’Brien patterned his stories after Poe and Charled D. Gardette was called a “Poesque tale writer” (Reynolds 377). Poe’s influence created duplicity in the lives of the Pfaffians; on one hand they were care-free revelers, on the other hand they took up melancholic airs to reflect him. The symbolism of Poe gave the otherwise aimless group something to appear to fight against, namely Capitalism and the emerging middle class. Although the group had aspersions to toss not only at the middle class but also the slavery allies, they were not activists for progression or change. Reynolds writes, “It was they (the Pfaffians)…who had no distinct aim or purpose…Their carefree, carpe diem attitude showed that fifties individualism had sunk toward anarchic decadence” (378).

Not all of the Bohemians continued to reject the middle class; in fact, the group who did not reject the middle class lifestyle lived much better lives than those who did. Miller writes that, “William Winter rose to become a powerful drama critic. Edmund C. Stedman became a wealthy stockbroker on Wall Street… Bayard Taylor became a noted man of letters…And Whitman transformed himself into America’s Great Gray Poet…” (90). Steadfast Pfaffians met many sad fates; Ada Clare died of rabies after she was bit by a dog (Parry 36), Adah Menken died of pneumonia in Paris, Clapp died an alcoholic pauper on Blackwell’s Island, Fitz-James O’Brien died in the Civil War and Artemus Ward (Miller 90), Fitz-Hugh Ludlow, George Arnold, and Ned Wilkins all died because of drug related issues (Kaplan 244). When those who stuck by Pfaff’s began to die off, the Vault suffered its own form of death. As prosperity moved north to Midtown, the Vault at Pfaff’s also moved leaving behind a shell that was only a memory of the golden years of Bohemia. The original building was destroyed and made into a store. Charles Pfaff died in 1890.

The Vault at Pfaff’s was the beginnings of the Bohemian lifestyle in New York City which took strong root in Greenwich Village and continues to this day in various ways. The Bohemian lifestyle has lent itself to short life expectancy due to the use of drugs and alcohol and the rejection of the norms of society. It is not surprising that Walt Whitman found himself comfortable in a space of such care-free individualism, even if he did set himself aside instead of making himself the center of the movement. Whitman outlived the original location of the Vault at Pfaff’s and the Pfaffian lifestyle, becoming the Great Gray Poet. Those Pfaffians who followed suit grew to prosper while those who did not follow such a course met early and tragic deaths. The Saturday Press precluded the demise of Henry Clapp; the lives of both the paper and the man ended in poverty. Surprisingly, Charles Pfaff lived a long life well into his late seventies, and the Bohemian lifestyle that was born and nurtured in his Vault continues to this day.

Works Cited

Reynolds, David. Walt Whitman’s America: A Cultural Biography. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., 1995.

Miller, Terry. Greenwich Village And How It Got That Way. New York: Crown Publishers, Inc., 1990.

Burrows, Edwin, and Wallace, Mike. Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898. New York: Oxford, 1999.

Parry, Albert. Garretts & Pretenders: A History of Bohemianism in America. New York: Cosimo, Inc., 2005.

Kaplan, Justin. Walt Whitman, A Life. New York: Perennial Classics, 2003.

Picture

Howells, William Dean. “First Impressions of Literary New York.” Harper’s New Monthly Magazine. Jun. 1895: 62-74.