The Whitman walking tour by Jesse Merandy was both informative and inspirational. The weather could not have been better as the air was crisp and the sun was shining as we met at stop number 1: the High Street subway entrance . What was most interesting of this spot was that Whitman himself worked here in the Rome Brother’s Print Shop. I particularly enjoyed this because it evoked for me the memory of reading about his work in the printing shop previously, at the age of 12 written about in Walt Whitman’s New York. In this particular passage he states, “What compositor, running his eye over these lines, but will easily realize the whole modus of that initiation? -the half eager, half bashful beginning- the awkward holding of the stick- the type-box, or perhaps two or three old cases, put under his feet for the novice to stand on, to raise him high enough- the thumb in the stick- the compositor’s rule- the upper case almost out of reach- the lower case spread out handier before him- learning the boxes- the pleasing mystery of the different letters, and their divisions- the great ‘e’ box- the box for spaces right by the boy’s breast- the ‘a’ box, ‘i’ box, ‘o’ box, and all the rest- the box for quads away off in the right hand corner- the slow and laborious formation, type by type, of the first line- its unlucky bursting by the too nervous pressure of the thumb- the first experience in ‘pi’, and the distributing thereof- all this, I say, what journeyman typographer cannot go back in his own experience and easily realize it?” (48). As we proceeded to the second location we passed the housing named after Walt Whitman (44-33 Henry Street)

. What was most interesting of this spot was that Whitman himself worked here in the Rome Brother’s Print Shop. I particularly enjoyed this because it evoked for me the memory of reading about his work in the printing shop previously, at the age of 12 written about in Walt Whitman’s New York. In this particular passage he states, “What compositor, running his eye over these lines, but will easily realize the whole modus of that initiation? -the half eager, half bashful beginning- the awkward holding of the stick- the type-box, or perhaps two or three old cases, put under his feet for the novice to stand on, to raise him high enough- the thumb in the stick- the compositor’s rule- the upper case almost out of reach- the lower case spread out handier before him- learning the boxes- the pleasing mystery of the different letters, and their divisions- the great ‘e’ box- the box for spaces right by the boy’s breast- the ‘a’ box, ‘i’ box, ‘o’ box, and all the rest- the box for quads away off in the right hand corner- the slow and laborious formation, type by type, of the first line- its unlucky bursting by the too nervous pressure of the thumb- the first experience in ‘pi’, and the distributing thereof- all this, I say, what journeyman typographer cannot go back in his own experience and easily realize it?” (48). As we proceeded to the second location we passed the housing named after Walt Whitman (44-33 Henry Street) . The second stop, Plymouth Church

. The second stop, Plymouth Church , was moving, especially upon entering the old church. It had the feel of being in the past as one of the students sat in the same row as Lincoln did many years earlier. One of the unusual things about the church was that the stained glass made no reference to angels or gods, they reflected men. The church was known for its involvement in the abolitionist movement and was part of the Underground Railroad. It was striking to me to hear that they had reverse slave auctions in where white people would buy the slaves’ freedom. The curator told us of one particular auction that involved “Pinkie”. Like her name, she was very light skinned, as her father was a white man. Being the daughter of a slave woman, she, despite appearance, was still bound to slavery until her freedom was bought at Plymouth Church. New York Magazine writes, “Most notable was the time a parishioner placed a small gold ring in the offering plate for a young slave girl named Pinkie, who returned to the church in 1927 to give thanks (and to return the ring)”(The Plymouth Church of Pilgrims, http://nymag.com/listings/attraction/plymouth-church-of-the-pilgrims/). Jesse Merandy then lead us down to the Brooklyn Promenade which gave us the vantage point of looking across that river as Whitman did many years ago before the Brooklyn Bridge was built. They say Whitman lived long enough to see the magnificent footings of the bridge constructed, but I am not certain that he ever crossed the bridge. We could see the waterways in which the ferries moved the residents of Brooklyn to the city of Manhattan.

, was moving, especially upon entering the old church. It had the feel of being in the past as one of the students sat in the same row as Lincoln did many years earlier. One of the unusual things about the church was that the stained glass made no reference to angels or gods, they reflected men. The church was known for its involvement in the abolitionist movement and was part of the Underground Railroad. It was striking to me to hear that they had reverse slave auctions in where white people would buy the slaves’ freedom. The curator told us of one particular auction that involved “Pinkie”. Like her name, she was very light skinned, as her father was a white man. Being the daughter of a slave woman, she, despite appearance, was still bound to slavery until her freedom was bought at Plymouth Church. New York Magazine writes, “Most notable was the time a parishioner placed a small gold ring in the offering plate for a young slave girl named Pinkie, who returned to the church in 1927 to give thanks (and to return the ring)”(The Plymouth Church of Pilgrims, http://nymag.com/listings/attraction/plymouth-church-of-the-pilgrims/). Jesse Merandy then lead us down to the Brooklyn Promenade which gave us the vantage point of looking across that river as Whitman did many years ago before the Brooklyn Bridge was built. They say Whitman lived long enough to see the magnificent footings of the bridge constructed, but I am not certain that he ever crossed the bridge. We could see the waterways in which the ferries moved the residents of Brooklyn to the city of Manhattan.

We further proceeded along the promenade down towards the Eagle Warehouse where Whitman worked for the Brooklyn Daily Eagle . I had been aware of the Eagle Warehouse for most of my life but had never made the connection that the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, which I was aware of, was printed there, and through this course finding that Walt Whitman wrote for the Daily Eagle. You could tell that part of the building was much older than others and had been added upon over time. It was very cool to be standing on a cobblestone street listening to Jesse Merandy, a Whitman scholar, speak of Whitman. As we attempted to go to our final stop, the Fulton Pier, it was closed due to a film shoot, so we wrapped up the tour there. Some of us went for pizza and some of us went back to school. I returned the next day to the Fulton Pier and stood upon the Pier, closed my eyes, and tried to imagine what it must have been like 150 years ago. Then I read the railing that had embedded in it the words of Whitman

. I had been aware of the Eagle Warehouse for most of my life but had never made the connection that the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, which I was aware of, was printed there, and through this course finding that Walt Whitman wrote for the Daily Eagle. You could tell that part of the building was much older than others and had been added upon over time. It was very cool to be standing on a cobblestone street listening to Jesse Merandy, a Whitman scholar, speak of Whitman. As we attempted to go to our final stop, the Fulton Pier, it was closed due to a film shoot, so we wrapped up the tour there. Some of us went for pizza and some of us went back to school. I returned the next day to the Fulton Pier and stood upon the Pier, closed my eyes, and tried to imagine what it must have been like 150 years ago. Then I read the railing that had embedded in it the words of Whitman

.

.

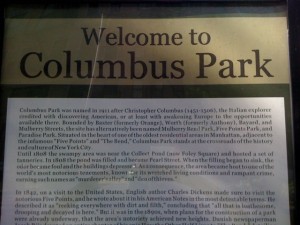

. Having parked my car on Mott, a block from Doyer, I had to pass through Columbus Park to get to Worth and Baxter. While in Columbus Park I came across the above pictured sign. It further confirmed the description that Dickens’ gave of the 5 points in his review of New York. The sign read as follows, “In 1842, on a visit to the United States, English author Charles Dickens made sure to visit the notorious Five Points, and he wrote about it in his American Notes in the most scathing terms. He described it as ‘reeking everywhere with dirt and filth,’ concluding that ‘all that is loathsome, drooping and decayed is here'”. The sign also quotes Danish newspaperman Jacob Riis and his description of the area in the 1890’s. It states, “Jacob Riis devoted an entire chapter of his epic How the Other Half Lives to ‘The Bend,’ detailing the ‘foul core of New York’s slums.’ He likened the filth and dearth of sunlight to a “vast human pig-sty,’claiming that “There is but one ‘Bend’ in the world, and that is enough.'” As I was reading the sign I introduced myself to an employee of the Parks Dept. to find the exact location of the Five Points. He suggested I was in the thick of it. Then I inquired where was the corner of Worth and Baxter and he pointed to a corner of the park. As I began to head in that direction I was approached by an elderly Asian woman who asked if I wanted to see the oldest part of the area. I said “yes”. She directed me to 15 Doyers St

. Having parked my car on Mott, a block from Doyer, I had to pass through Columbus Park to get to Worth and Baxter. While in Columbus Park I came across the above pictured sign. It further confirmed the description that Dickens’ gave of the 5 points in his review of New York. The sign read as follows, “In 1842, on a visit to the United States, English author Charles Dickens made sure to visit the notorious Five Points, and he wrote about it in his American Notes in the most scathing terms. He described it as ‘reeking everywhere with dirt and filth,’ concluding that ‘all that is loathsome, drooping and decayed is here'”. The sign also quotes Danish newspaperman Jacob Riis and his description of the area in the 1890’s. It states, “Jacob Riis devoted an entire chapter of his epic How the Other Half Lives to ‘The Bend,’ detailing the ‘foul core of New York’s slums.’ He likened the filth and dearth of sunlight to a “vast human pig-sty,’claiming that “There is but one ‘Bend’ in the world, and that is enough.'” As I was reading the sign I introduced myself to an employee of the Parks Dept. to find the exact location of the Five Points. He suggested I was in the thick of it. Then I inquired where was the corner of Worth and Baxter and he pointed to a corner of the park. As I began to head in that direction I was approached by an elderly Asian woman who asked if I wanted to see the oldest part of the area. I said “yes”. She directed me to 15 Doyers St . which was very close to where I parked the car. She had suggested that there was a passageway under the buildings about three stories down. I was excited to hear this as Dickens has been in my head since reading his review of New York, especially the part where he describes, “Ascend these pitch-dark stairs, heedful of a false footing on the trembling boards, and grope your way with me into this wolfish den, where neither ray of light nor breath of air, appears to come. A negro lad, startled from his sleep by the officer’s voice-he knows it well-but comforted by his assurance that he has not come on business, officiously bestirs himself to light a candle. The match flickers

. which was very close to where I parked the car. She had suggested that there was a passageway under the buildings about three stories down. I was excited to hear this as Dickens has been in my head since reading his review of New York, especially the part where he describes, “Ascend these pitch-dark stairs, heedful of a false footing on the trembling boards, and grope your way with me into this wolfish den, where neither ray of light nor breath of air, appears to come. A negro lad, startled from his sleep by the officer’s voice-he knows it well-but comforted by his assurance that he has not come on business, officiously bestirs himself to light a candle. The match flickers which furthered my feelings of an unkempt underground passage. There were several staircases and some closed exits blocked by garbage cans

which furthered my feelings of an unkempt underground passage. There were several staircases and some closed exits blocked by garbage cans ; it felt as though I traveled several stories underground before finding myself at the foot of the stairs. I then proceeded down a winding and turning hallway

; it felt as though I traveled several stories underground before finding myself at the foot of the stairs. I then proceeded down a winding and turning hallway which felt as though it was longer than two city blocks. There were several shops, most of them abandoned, and the few that were open (one being an employment agency) had signs written in Chinese. It gave an overall feeling of being in an unfamiliar place, such as Dickens must have felt on his first voyage to New York. At the end of the long and winding corridor I found myself looking up a long flight of stairs with an exit sign. As I proceeded up the stairs I felt the sunlight shining

which felt as though it was longer than two city blocks. There were several shops, most of them abandoned, and the few that were open (one being an employment agency) had signs written in Chinese. It gave an overall feeling of being in an unfamiliar place, such as Dickens must have felt on his first voyage to New York. At the end of the long and winding corridor I found myself looking up a long flight of stairs with an exit sign. As I proceeded up the stairs I felt the sunlight shining in through the glass door and walked out into Chatham Sq.

in through the glass door and walked out into Chatham Sq. After my impromptu adventure, set off by the elderly Asian woman, I returned to the corner of Baxter and Worth

After my impromptu adventure, set off by the elderly Asian woman, I returned to the corner of Baxter and Worth and took in the view of the Five Points (Columbus Park) from that vantage point. It being so early in the morning with so few inhabitants it was easy to imagine what it must have been like in the 1800’s thanks to the culmination of the readings, the park, and my short adventure underground.

and took in the view of the Five Points (Columbus Park) from that vantage point. It being so early in the morning with so few inhabitants it was easy to imagine what it must have been like in the 1800’s thanks to the culmination of the readings, the park, and my short adventure underground.