The brown-sugar shortbread I’m baking for my Whitmaniacs is in the oven, the freshman final exams I should be grading are stacked beside me, my children are sleeping all snug in their beds, and I am melancholy that tomorrow effectively disbands the Digital Whitman Fellowship. There is much work undone. By Friday morning the heaviest of those burdens will be grading final projects, but tonight it’s the realization that I’ve never really blogged about the Womanly Whitman. Since naming him in response to Dr. Earnhart’s famous James Bond Speech on our first night of class in August, God knows I’ve talked about him, I’ve watched students and two other professors at UMW pick up the term, I’ve mentioned him to Barbara Bair, the Library of Congress archivist who changed our semester. But he deserves one final huzzah here on I Give You My Hand.

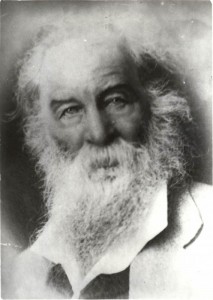

Before this project, I taught Whitman a lot, in three or four different courses, but had come to focus almost solely on “Song of Myself”– sometimes 1855, sometimes Deathbed, sometimes with humor, sometimes with aggravation, always with an appreciation for poetic genius, and always with a pretty clear picture in my head of the kind of guy I was dealing with: macho, swaggering, egotistical. You know, this guy:

The Enhanced Manly Whitman

Even his radical inclusion had begun to feel at best appropriative, at worst cannibalistic, consuming the American people to feed his vast, virile self. “Song of Myself” was like a poetic codpiece. I couldn’t see the forest for the fibres of manly wheat. You understand me.

I exaggerate, of course, but don’t entirely lie. During the re-immersion in Whitman that I undertook about a year ago, something happened. In between blaming Whitman for Charles Olson and rolling my eyes at his father-stuff, I began to see someone unexpected emerging–someone with soft hips and warm eyes, someone surprisingly quiet, a good listener, a bringer of lemons and ice cream, a moon-watcher. This person:

The Marriage Photo, with pleased smiles and fleshy hips

And this one:

This Whitman appeared in the memoirs of his friends, in letters to his mother, and, powerfully, in the Civil War writings to which I was turning fresh and focused attention. (To my surprise, when I went back to “Song of Myself,” of course this Whitman was all over it.) Right now my favorite work of this Whitman may be “Vigil Strange I Kept on the Field One Night,” which is here.

“Vigil Strange” imagines a private wake for a young dead soldier, kept through the night by an older, grieving comrade. It is not a perfect poem, being marred by weird syntactic inversions and being, arguably, maudlin. But it is intensely moving in the quietness of its grief:

Till late in the night reliev’d to the place at last again I made my way,

Found you in death so cold dear comrade, found your body son of responding kisses, (never again on earth responding,)

and its acceptance of the unacceptable:

Passing sweet hours, immortal and mystic hours with you dearest comrade—not a tear, not a word,

Vigil of silence, love and death, vigil for you my son and my soldier,

As onward silently stars aloft, eastward new ones upward stole . . .

and in its exquisite, unbearable gentleness:

My comrade I wrapt in his blanket, envelop’d well his form,

Folded the blanket well, tucking it carefully over head and carefully under feet,

And there and then and bathed by the rising sun, my son in his grave, in his rude-dug grave I deposited. . .

“Vigil Strange” has a rhythm that approaches incantation or lullaby–long, frequently repetitive lines that are calming (cut short abrasively by the reality of war in the aborted rhythm of the final line/action: “And buried him where he fell”). The swaddling of the “son,” “my soldier,” in his blanket is, I’m going to suggest, not masculine, not even paternal. It is maternal, tender, womanly.

What problems arise from my assertion? A lot, and two of them have to be addressed. First, unquestionably my desire to call this voice the Womanly Whitman is rooted heavily in a construction of the womanly and the maternal that is traditional, nurturing, compassionate, the angel in the hospital ward. It is the construction I invoked in the domestic scene that began this post. It is a construction with which I am utterly at odds ideologically and which I have doggedly and sometimes fiercely interrogated in my teaching, my politics, and many of my life choices. Second, there is a complication in casting the speaker of “Vigil Strange” as maternal, a Freudian complication best indicated by the title from Lawrence (curse, growl): “Sons and Lovers.” My casting of this soldier as maternal effectively recontains the homoeroticism of the poem:

One look I but gave which your dear eyes return’d with a look I shall never forget,

One touch of your hand to mine O boy, reach’d up as you lay on the ground,

Then onward I sped in the battle, the even-contested battle,

Till late in the night reliev’d to the place at last again I made my way,

Found you in death so cold dear comrade, found your body son of responding kisses, (never again on earth responding,)

The language of “my son,” “dear eyes,” and “boy” can mask the power of that body, those kisses, the assertion of love that will transcend death (less so, perhaps, if you’ve read the repeated use of the word “son” in Whitman’s letters to his partner Peter Doyle). OR, and this is equally problematic, I am mapping “gay” over “tender, feminine, womanly” as though they are fundamentally interchangeable.

Oy vey. Now I’m really in the total animal soup of essentialism.

But I want that term. Maybe because in some ways it is MY “womanly”– that is to say, “womanly” is a tag not unlike the “myWW” tag I append to certain posts to indicate a connection to Whitman that goes beyond admiration of the poetic line, the image, the nest of guarded duplicate eggs you have to have to throw over the literary establishment. It is, I will say on safer ground, a non-patriarchal Whitman: tender, generous, nurturing, doubting, equalizing. It’s the Whitman this semester has given me, and I’m grateful.