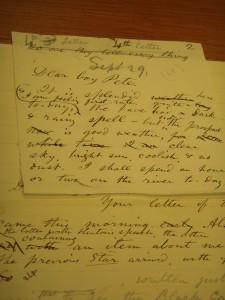

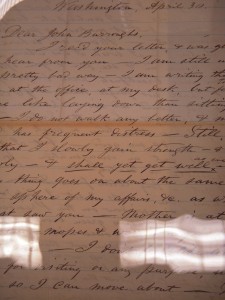

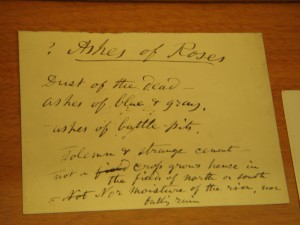

On our field trip to Washington DC, as we doggedly trekked back to the cars, Chelsea and I fell into conversation about Whitman’s letters. Of course, we were thrilled to have seen them and nearly touched them. The preciseness of Whitman’s handwriting and the possibility that one of the letters might have had his fingerprint was incredible. What was even more incredible about the letters, I think, was the fact that they were physical evidence of Whitman’s transcendence of time. Not only had his words and thoughts survived, but they were still able to touch a group of college students and turn them into weepy messes. Even something as simple as his revisions brought on tears, and then his letters…Oh, Walt. I know I’ve said this before, but the “I will get well yet” will always stick with me.

It got both Chelsea and I thinking: in the age of technology, with emails and AIM, what is our legacy going to be like? Emails and IMs are deleted within minutes and what with their ability to be instantaneous, I think we tend to make them a lot more impersonal. There’s just something lacking when you type in Times New Roman, size 12. Furthermore, where are they going to be saved? How are we going to pass some of these things on for people a hundred years ahead?

Granted, I think part of the reason we are able to take Whitman’s letters to heart today is because he knew he was going to be pretty special. Score one for egotism But I can’t help wonder what his legacy would be like if Whitman was reduced to 140 characters (sorry, Jim Groom!). At any rate, the idea has made me get out my pens and write some letters via snail mail. I even sealed them with wax. So maybe I’m not going to be famous like Whitman, and future generations would probably care less what I wrote to my grandmother, but at least my children might one day get a glimpse of what I and my super trippy handwriting were like (I’ve been told I have the cursive of a serial killer, seriously).

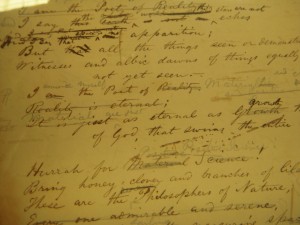

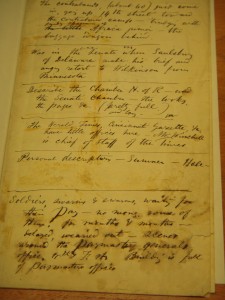

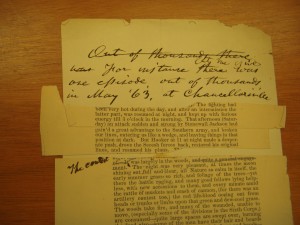

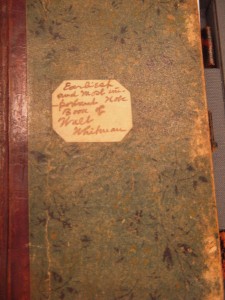

Okay. At the risk of this not having anything much to do with our field trip, I’m going to post several of the pictures of Whitman’s letters and handwritten notes. I dare you not to tear up a little (or at least the Whitmaniacs in Digital Whitman, anyway).