The funeral procession in Washington en route to the capitol.

Lincoln's Funeral Hearse in Washington. It was pulled by six white horses.

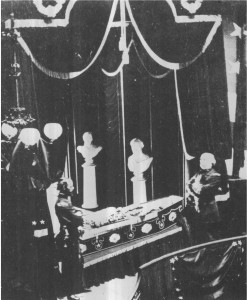

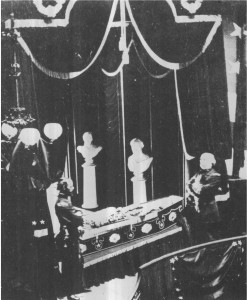

This is the only proven picture of Lincoln in death.

Lincoln was shot on April 15, 1865, at Ford’s Theater in Washington, DC (Kunhardt 119). Within hours of his death, Washington was scrambling to work on the preparations. The undertaker worked nearly nonstop 24 hours to produce Lincoln’s $1500 coffin, which measured 6 feet 6 inches long, a tight fit for Lincoln’s 6 feet 4 inches. Curiously, the coffin was decorated with four shamrocks on each side, with a star on the center of the broadest leaf. No one had ordered this. It has also never been explained, except that perhaps the undertaker’s artist was Irish, and was told to design something meaningful (120).

Before the funeral, Lincoln’s body rested on a catafalque (a raised platform used to support a casket) in East Room of the White House. The structure stood as high as eleven feet, was eleven feet long, and was decorated with draped black velvet and crape. Designed by Benjamin B. French, it mimicked the “Lodges of Sorrow,” which are the central component in Masonic funerals. The underside of the canopy was white fluted satin, which was intended to catch the little light in the room and reflect it on the corpse’s face. Lincoln’s catafalque soon came to be known as the “Temple of Death,” because it stood in the White House a full five weeks; Mary Todd Lincoln was so distraught that she begged officials not to take it down until she had moved out of the White House (120). Although small changes have been made to reinforce the structure, Lincoln’s catafalque is still used today for the funerals of presidents; it was most recently used for former President Ford’s (121).

The public in Washington was allowed to view the body that Tuesday. Lincoln’s official funeral was scheduled for Wednesday, April 19 (130). The city was packed; over a hundred thousand people had come to watch the procession and say goodbye to the president. Most arrived already in mourning, decorated with black crape tied to their arms, or pictures of Lincoln hanging over their hearts (123), and people were scrambling for places. Window seats cost as much as $100 (147). Wednesday began with the booming of cannons from all the forts surrounding the city, as well as bells tolling from the churches and fire departments. At exactly 12:10, Dr. Hall began the Episcopal burial service. Then, Bishop Simpson of the Methodist Episcopal Church spoke, and Dr. Gurley, Lincoln’s pastor, delivered the funeral sermon (Goodrich 188). While this was going on, all over the nation, and even in Canada, there were similar services being delivered for the president (Kunhardt 129).

The procession to the capitol soon followed the funeral. Once the coffin had been loaded on to the car, which was pulled by six white horses, the bells and cannons resumed. A detachment of black soldiers led; they had been the second troop to enter Richmond upon its surrender. Black citizens made the most impressive showing of grief out of all the mourners at the procession; nearly 4,000 walked in lines of forty straight across the road, holding hands and carrying signs. Just following the hearse was Lincoln’s favorite horse, which had been branded “U.S.” and was carrying his master’s boots backwards in the saddle (131). Once they reached the capitol, the body was then laid in the rotunda for several days, and the public was again allowed to view Lincoln.

Lincoln’s popularity and martyrdom caused an insurmountable amount of grief around the city. Lincoln was a legend, and just as when any legend dies, so do more legends and tales spring up. Some people claimed that the day of the funeral, a bright star had appeared in the sky over Washington. Another tale said that no wood thrush sang for an entire year after Lincoln’s death (132).

Mary Todd Lincoln never attended Lincoln’s funeral, or any of the following ones. She remained in bed nearly the entire time, claiming that she was too upset. When they moved the body to the catafalque, the bearers even removed their shoes because they were afraid that she would hear their footsteps and begin screaming(Goodrich 185). Mary Todd Lincoln also spoke to spiritualists claiming to have messages from her dead husband, which did not help her erratic nature. Nevertheless, these were the few people she would allow to see her. Eventually, Robert Lincoln put a firm stop to it in hopes that it would help soothe his mother (Kunhardt 249).

Although Lincoln’s official funeral was in Washington, DC, he was to have at least 12 more. His body was placed on a train on Friday, April 21st, so that it could travel part of the country and give citizens a chance to say goodbye . The body would end up in Springfield, where Lincoln would eventually be buried. Mary Todd Lincoln had also decided that their son, Willie, who had died three years earlier, would be exhumed and re-interred with his father (Goodrich 195). Both coffins were placed side by side in the second to last railway car and were joined by 300 passengers, containing officials, family members, and individuals integral to the cortege (Kunhardt 139).

The train’s trip was intended to include every city which the president-elect had stopped on his trip eastward to Washington in 1861: Baltimore, Harrisburg, Philadelphia, New York, Albany, Buffalo, Columbus, Indianapolis, Chicago, and finally, home to Springfield. The only exception to this was Cincinnati, which was ruled out because they deemed the southward trip too lengthy, much to the offense of the city (140).

The train was always greeted with enormous crowds and displays of mourning, almost as if each city was trying to outdo the others. One viewer disgustedly remarked that the great show made “their mourning…a fashion…[M]any come to such sights as they would to a wax work show” (Goodrich 232). Citizens often held signs that expressed such feelings as “Abraham Lincoln, the illustrious martyr of liberty, the nation mourns his loss, though dead, he still lives” (197). Before the public was allowed to view Lincoln, the undertaker had to quickly chalk the corpse’s face to hide discoloration, as well as literally dust him off. The constant opening and closing of the coffin, as well as the dirty state of most of its visitors often left Lincoln’s body nearly caked in grime (196).

Philadelphia’s funeral was one of the few marked by violence. When the train first arrived, an artillery piece exploded prematurely, injuring two people; this was an early indicator of the violence that was soon to come (197). Before the train had even arrived, mourners stood for miles even before the station; there were no gaps in the lines that stretched as far north as the Schuylkill River and as far east as the Delaware River (Kunhardt 150). When pickpockets began terrorizing a portion of the crowd (an act that was not uncommon during the funerals; gangs of pickpockets followed the train (Goodrich 236)), the line changed into a mob, and surged out far beyond the guiding ropes. Someone then cut the guiding ropes, which resulted in chaos. People began fighting. Many women fainted, and had to be passed out above the heads of the crowd (Kunhardt 150). Individuals also had their clothes ripped off of them, so that the streets were littered with torn petticoats and shirts (Goodrich 199). Police began sending people at the front of the mile-long line back to the end. By the end of the day, at least one woman had broken her arm, and two small boys were said to be dead, although they were later revived (Kunhardt 150). Because of the violence, police ensured a no-tolerance policy over the body; individuals were not allowed to stop and look at the body for even a second during the viewing, and many people had to be prevented from touching or even kissing Lincoln’s face (Goodrich 214).

The stop at New York was also marked with similar police action; they were said to bully the crowds and immediately escort out anyone who looked suspicious. The New York City Council ruled that colored citizens were not allowed to walk with the procession, much to the chagrin of the thousands of citizens that had come to see the president that had freed them (Kunhardt 153). However, the Secretary of War quickly sent a telegram to the city in response, begging that “no discrimination respecting color should be exercised in admitting person to the funeral procession” (154). 300 citizens marched, bearing a sign that said “Two million of bondsmen he liberty gave.” Their passing was the only time that applause broke out during the procession. Unfortunately, their dream of marching with the president did not entirely come true; the body was already out of New York and traveling up the Hudson by the time they walked(155).

When the body finally reached Illinois, the embalmers were having a lot of issues; onlookers often commented on how black the president’s face was becoming, as well as his shriveled appearance and pitted cheeks (Goodrich 242). One viewer likened him to a “mummy” (Kunhardt 240). Although he had finally gotten to his home state, Lincoln’s final resting place was still the source of much debate; Mary Todd wanted to choose the place that her husband would have wanted. Chicago was her first choice because it was where Lincoln had planned on settling after his presidency. Her second choice was the tomb built for Washington under the rotunda of the capitol (247). Finally, she decided on a cemetery outside of Springfield called “Oak Ridge,” because her husband wanted to be buried “in a quiet place” (248). Springfield citizens did not agree; they thought it was too far out of town. Instead, they purchased a stone house closer to the center of town, and began working that into a tomb. When Mary Todd Lincoln heard this, she was furious, and threatened to bury Lincoln in Chicago instead (242). The fight between the two parties grew so intense that Springfield citizens insisted Mary Lincoln had “no friends here” (249). Robert Lincoln put an end to the matter by quickly traveling to Springfield; Mary Lincoln again remained confined to her room. Finally, on May 4, 1965, nearly three weeks after Lincoln had been killed, he and his son were laid to rest . After 1700 miles (243), violence, celebration, and grief, Lincoln’s body had found its final home.

Works Cited

Goodrich, Thomas. The Darkest Dawn. Bloomington: University of Indiana Press, 2005. Print.

Gurney, Jeremiah Jr. “Lincoln in Death.”Photograph. Kunhardt, Dorothy Meserve and Philip B. Kunhardt Jr. Twenty Days. New York:Harper and Row Publishers, 1965, 162. Print.

Kunhardt, Dorothy Meserve and Philip B. Kunhardt Jr. Twenty Days. New York: Harper and Row Publishers, 1965. Print.

“Lincoln’s Funeral Train.”Photograph. Kunhardt, Dorothy Meserve and Philip B. Kunhardt Jr.Twenty Days. New York:Harper and Row Publishers, 1965, 147. Print.

“Washington During the Funeral.” Photograph. Kunhardt, Dorothy Meserve and Philip B. Kunhardt Jr. Twenty Days. New York:Harper and Row Publishers, 1965, 130. Print.