Thanksgiving in Serbia: in loving memory of Philipp Karbiener, 1 March 1935 (Sekitsch, Yugoslavia) – 22 November 2002 (Glen Cove, NY, USA)

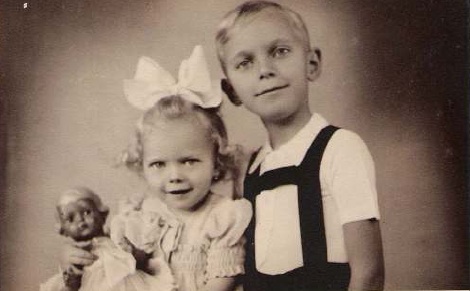

One of our family's treasures is this rare photo of my father and Inge, taken before the onset of Tito's expulsion campaigns in 1944.

21 November 2009.

All day long I walked around thinking that this was the anniversary of Daddy’s death. I lit a candle for him in the Serbian Orthodox Church in Zrenanin, and told Aleksandra’s mother (who had made some vanille krenzen for a lavish St. Michael’s Day feast I was treated to today) that these were my father’s favorite cookies, that he would be pleased to see (even more to eat) them. I just called my friend Jackie Gardy to tell her no, I wouldn’t be able to come to the Novi Sad Jazz Festival tonight, that I wasn’t up to it. You see, seven years ago, I lost my beloved dad. His end was sudden and quick, the result of a brain anheurism and, undoubtedly, more than a lifetime of trauma and hard work. In 2002, November 22 became the most difficult day imaginable. And every year on this date, I allow myself to be engulfed by floods of memories and emotions. November 22 marks my counter-celebration of self-pity and grief.

Well, November 22 is tomorrow.

I only realized that when I looked at my calendar a moment ago. Today’s the twenty-FIRST, not the twenty-SECOND, of November. So that call to my mom, and the drama of thinking about my father on this heaviest of days, could wait another day.

But it felt like today, like today was connected with that other day in 2002 when I last spoke to my father in person and when I had angry words with a thoughtless, disconnected doctor in Glen Cove Hospital, about disconnecting my father from life support. Such a strange day. I was teaching at Colby College at the time, and had flown down from Maine to New York the day before, at my sister’s request. Dutifully teaching my last pre-Thanksgiving classes and giving my students assignments for the break, I drove to Portland Airport in a daze. When the fog lifted, I was holding my father’s hand in the hospital and thinking about what I needed to tell him.

I will write the story, Daddy. I promise.

And then blurriness and hospital smell, and then Tante Inge’s arrival and then waiting. And then hope and then not. And then blankness.

My father is the reason that I am writing to you from Serbia. He, along with my great-grandfather, are my loving courage-teachers, my representatives of what the best of us can aspire to be. Philipp Karbiener (or, as his birth record reads, Филип Михаел КАРБИНЕР) was the first son born to one of the wealthiest households in Sekitsch, Yugoslavia in 1935. His grandfather, who had served as the mayor of Sekitsch and had expanded the family’s properties and wealth, saw more potential in the steady gaze of his grandson (see photo above) than in the boy’s father. From an early age, my dad had received tutelage on land and agricultural management; by age nine, he was a skilled horseman who could gentle-break the wildest stallion on any of the family’s four farms.