| |

Sep 13

“Content with the present, content with the past,

By my side or back of me Eve following,

Or in front, and I following her just the same” (248)

Right away, in the first poem of “Children of Adam,” “To the Garden of the World,” Whitman proposes a utopia that most of us cannot fathom as ever being America. But, as he addresses “the world anew ascending” (248), he brings to mind both the biblical Garden of Eden as well as the developing nation. His act of situating America as the “garden of the world” surfaces many interesting ideas understood through exploring several points of comparison between Eden and the way Whitman sees our nation.

Suggesting that one be “content with the present, content with the past” drives home a point that I brought up in class on Tuesday. That is, that Whitman is concerned with and urges America to ascertain itself in the present, and further, to be ok with it. In Eden, utopia was lost to Adam and Eve after they ate of the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge, but through eating the fruit, they exchanged ignorance for knowledge even if it came hand in hand with a trade of bliss for suffering. Beginning anything is, in many ways, an act of embracing a world of ignorance; therefore, the people breaking away from England to begin America were readily exchanging knowledge, comfort, and protection, for vast ignorance and uncertainty. But, through this line, Whitman urges the people of America to think on this transition only in a way that brings them contentment, and to embrace the here and now as it comes rather than concern themselves with fear or regret.

Further, Whitman introduces the importance of equality (most directly between men and women here) as a necessary ingredient to achieving contentment with the present and past when he introduces Eve. Though many of you have been grappling with Whitman’s view on women and what role he desires that they play in his America, (I am still struggling with that myself) it is clear here that, at the very least, he acknowledges women’s importance and presence in the setting forth on this journey into knowledge and discovery. Whitman suggests that every man and every woman may relate to one another at this level because no one knows what is ahead and therefore it makes no difference who leads and who follows; everyone is embarking on new territory.

Lastly, (well, for this blog at least) Whitman’s positioning of himself as Adam allows him to become, figuratively speaking, the man who begat all other men. This is Whitman again placing himself as the leader, the prophet, the father of the American people, allowing him to present himself as the poet America “needs” (as we discussed extensively in class last week). His role as Adam is important because it suggests that he, being the first man, was made in the direct image of God and therefore may be considered closest to him. It also makes the claim, as this poem seems to put an optimistic spin on the usually depressing story of the expulsion from Eden, that walking away from the direct presence of God, or any authority, to discover one’s own way may be a better and more exhilarating way to achieve peace and unity.

Sep 07

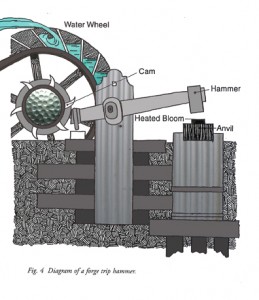

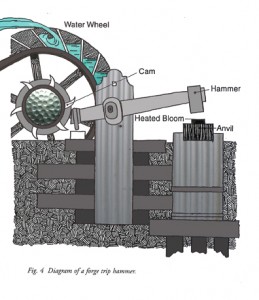

“Where triphammers crash….where the press is whirling its cylinders” (60)

Triphammer: a massive power hammer having a head that is tripped and allowed to fall by cam or lever action (Merriam-Webster)

See how a triphammer works…

(http://explorepahistory.com/displayimage.php?imgId=3905)

Triphammers were often powered by a water wheel and are known to have been used as early as 20 AD in China. They were used widely for blacksmithing until the Industrial Revolution. At that time, triphammers fell out of favor and were replaced with something referred to as simply, the power hammer (Reference.com). As the Industrial Revolution occurred prior to Whitman writing “Song of Myself”, it is interesting that he writes of this older technology instead of proclaiming, “Where the power hammers…” This perhaps shows Whitman’s attention to all things going into and coming out of “revolutions” or any other change that America goes through. Earlier in the poem he writes, “I am afoot with my vision,” (59) and Whitman is afoot with his vision everywhere, even where technology is not yet advanced, or where people are not yet advanced.

Tags: imagegloss

Sep 06

“A Supermarket in California” – Allen Ginsberg

What thoughts I have of you tonight, Walt Whitman, for I walked

down the sidestreets under the trees with a headache self-conscious looking

at the full moon.

In my hungry fatigue, and shopping for images, I went into the neon

fruit supermarket, dreaming of your enumerations!

What peaches and what penumbras! Whole families shopping at

night! Aisles full of husbands! Wives in the avocados, babies in the tomatoes!

–and you, García Lorca, what were you doing down by the watermelons?

I saw you, Walt Whitman, childless, lonely old grubber, poking

among the meats in the refrigerator and eyeing the grocery boys.

I heard you asking questions of each: Who killed the pork chops?

What price bananas? Are you my Angel?

I wandered in and out of the brilliant stacks of cans following you,

and followed in my imagination by the store detective.

We strode down the open corridors together in our solitary fancy

tasting artichokes, possessing every frozen delicacy, and never passing the

cashier.

Where are we going, Walt Whitman? The doors close in a hour.

Which way does your beard point tonight?

(I touch your book and dream of our odyssey in the supermarket and

feel absurd.)

Will we walk all night through solitary streets? The trees add shade

to shade, lights out in the houses, we’ll both be lonely.

Will we stroll dreaming of the lost America of love past blue automo-

biles in driveways, home to our silent cottage?

Ah, dear father, graybeard, lonely old courage-teacher, what America

did you have when Charon quit poling his ferry and you got out on a

smoking bank and stood watching the boat disappear on the black waters of

Lethe?

“On a Love Theme by Walt Whitman” – Allen Ginsberg

I’ll go into the bedroom silently and lie down between the bridegroom and the bride, those bodies fallen from heaven stretched out waiting naked and restless, / arms resting over their eyes in the darkness, / bury my face in their shoulders and breasts, breathing their skin, and stroke and kiss neck and mouth and make back be open and known, / legs raised up crook’d to receive, cock in the darkness driven tormented and attacking / roused up from hole to itching head, / bodies locked shuddering naked, hot hips and buttocks screwed into each other / and eyes, eyes glinting and charming, widening into looks and abandon, / and moans of movement, voices, hands in air, hands between thighs, hands in moisture on softened lips, throbbing contraction of bellies till the white come flow in the swirling sheets, / and the bride cry for forgiveness, and the groom be covered with tears of passion and compassion, / and I rise up from the bed replenished with last intimate gestures and kisses of farewell – / all before the mind wakes, behind shades and closed doors in a darkened house / where the inhabitants roam unsatisfied in the night, nude ghosts seeking each other out in the silence.

I just wanted to put these poems out there for your reading pleasure…I’ll probably talk more about them later. I enjoy Ginsberg’s work and was delighted to come across these poems. The second poem is particularly interesting for where we are in the class as it is a response to a portion of “A Song of Myself” where Whitman writes, “I turn the bridegroom out of bed and stay with the bride / myself, / And tighten her all night to my thighs and lips” (64). (Sorry the format of the second is without line breaks)

Sep 06

After briefly discussing Whitman’s view of America last Tuesday and then reading Fuller’s essay on American literature, I became even more interested in the way Whitman presents himself to his nation as well as how he feels the nation presents itself to him and to the American people. Whitman urges, even requires us to take a step back and examine the “big picture”; he desires us to consider America as one expansive but unified plane that delights in its differences and diversities rather than allows them to act as a divider. This is achieved, he seems to suggest, when each person takes an active role in educating his or herself. He says, as Professor Earnhart read last week, “Books are to be call’d for, and supplied, on the assumption that the process of reading is not a half sleep, but, in highest sense, an exercise, a gymnast’s struggle” (1016). Whitman is saying, Wake up, America! This is the reason we are here. Take advantage of your ability to be different, to be free!

Despite this command and call, Whitman also seems to realize that America still has a long way to go before its people are completely unified. This is what Margaret Fuller was getting at in her essay, particularly when she discusses America’s relationship with England and its tendency to borrow from England’s practices and culture even when those practices are incongruous with the United States Constitution. Whitman, perhaps inspired by Fuller’s article, speaks directly to this problem throughout his work. He seems to agree that America is a separate and individual nation and that it needs to start acting like one by, at a minimum, learning to embrace its entire people. It is for this reason that education becomes so important. By striving to achieve an education, each individual becomes more cognizant of the thread which binds all human beings. He or she also begins to realize that learning not only expands knowledge, but often encourages acceptance and dissolves prejudice. When one can learn to understand that all people are equal, he or she will begin to see in their surroundings the ways in which people are connected. In “Crossing the Brooklyn Ferry,” Whitman writes, “What is more subtle than this which ties me to the woman or man that looks in my face? / Which fuses me into you now, and pours my meaning into you?” (312) as well as claims throughout the poem, “I, too…” in order to better illuminate the benefits of accepting that people can be connected through experience or even through the very act of living.

Adrienne Riche, in her commencement address titled “Claiming an Education,” says, “you cannot afford to think of yourselves as being here to receive an education; you will do much better to think of yourselves a being here to claim one” (Riche 19). Though Riche was speaking to a women’s college nearly a century later (in 1977), Whitman would have undoubtedly agreed that being active in seeking an education is the only way to truly learn. He continues in “Democratic Vistas” to stress that active learning will produce “a nation of supple and athletic minds, well-train’d, intuitive, used to depend on themselves, and not on a few coteries of writers” (1017). It is through education and learning to accept and even embrace differences that make America what it is intended to be, a nation that is truly by the people and for the people.

Riche, Adrienne. “Claiming an Education” Women: Images and Realities. Eds. Amy Kesselman, Lily D. McNair, Nancy Schniedewind. New York: McGraw Hill, 1995. 19-21.

Aug 31

Apart from the pulling and hauling stands what I am,

Stands amused, complacent, compassionating, idle, unitary,

Looks down, is erect, bends an arm on an impalpable certain rest,

Looks with its sidecurved head curious what will come next,

Both in and out of the game, and watching and wondering at it.

Backward I see in my own days where I sweated through fog with linguists and contenders,

I have no mockings or arguments…I witness and wait.

Tags: frontispiece, ww20

Aug 30

So far, I am torn between overwhelming agreement with Walt Whitman and confusion over his occasional self-contradiction. Though he seems at times to have some semblance of a self-righteous Christ complex, his ideas about the world and most particularly about poets and poetry are quite inspiring. His passion and insistence that the United States will yield and revere the greatest poets are sentiments which are unfortunately no longer shared by the greater part of society (just ask to see Dr. Scanlon’s newspaper write-in from a reader who wrote to complain over the government paying poet laureates). However, it is refreshing to view and understand a poet as being of the highest regard in a community, though it seems Whitman would take this esteem to the highest elevation. This is where the aforementioned Christ complex kicks into gear.

The didactic language of the introduction to Leaves of Grass as well as in this version of “Song of Myself” help to make the poet and therefore Whitman himself into an omnipotent Christ figure. Throughout the introduction, Whitman manipulates biblical language and allusion so that the poet may be better imagined this way. In addition to how greatly the poet is praised, there are specific instances where he is placed in the exact position of the biblical Messiah. For example, Whitman writes, “The greatest poet forms the consistence of what is to be from what has been and is. He drags the dead out of their coffins and stands them again on their feet….he says to the past, Rise and walk before me that I may realize you” (13). This allusion to the story of the resurrection of Lazarus as told in the book of John (11:38-44) allows the poet to take the place of Christ. Later in the introduction, Whitman uses similar biblical language that seems reminiscent of the ever popular 1 Corinthians 13:4-7 which begins “Love is patient and kind” when he says, “Liberty relies upon itself, invites no one, promises nothing, sits in calmness and light, is positive and composed, and knows no discouragement” (17). Whitman also sets up his own version of the commandments (though there are more than ten) when he writes, “This is what you shall do: Love the earth and the sun and the animals…” (11). Another scriptural allusion, though perhaps a bit more under the radar is, “A new order shall arise and they shall be the priests of man, and every man shall be his own priest” (25). This is strikingly similar to 1 Peter 2: 9a which says, “But you are not like that, for you are a chosen people. You are a kingdom of priests, God’s holy nation, his very own possession.” The list of biblical allusion goes on and on.

At this point, Whitman’s stance on religion has me both puzzled and intrigued. Clearly he is educated in the Bible as his work is full of both traditional biblical allusion and less obvious biblical language, though he seems often to rebuke and/or manipulate its teachings to fit his own ideas about religion. I have been tempted to argue that Whitman abandons faith for the idea that man or nature is supreme (or rather that he places his faith in those things), though I can’t quite get around the fact that he does not completely reject the idea that God exists (as he brings Him up many times throughout the introduction to Leaves of Grass and “Song of Myself”). Perhaps Whitman would today consider himself a universalist? It seems that these doubts and questions are some I will grapple with over the course of the semester. Even Whitman himself admits to his self-contradiction when he writes, “Do I contradict myself? / Very well then….I contradict myself; / I am large….I contain multitudes” (87). Well Walt, I guess it’s me versus your multitudes…

Tags: God, religion

|

|

Recent Comments