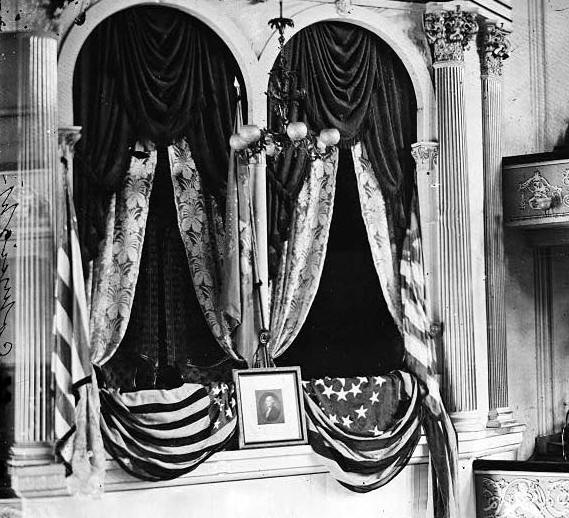

Ford’s Theatre 1865

http://www.historydc.org/onlineexhibit/LincolnsWashington/Mr.%20Lincoln’s%20Assassination.asp

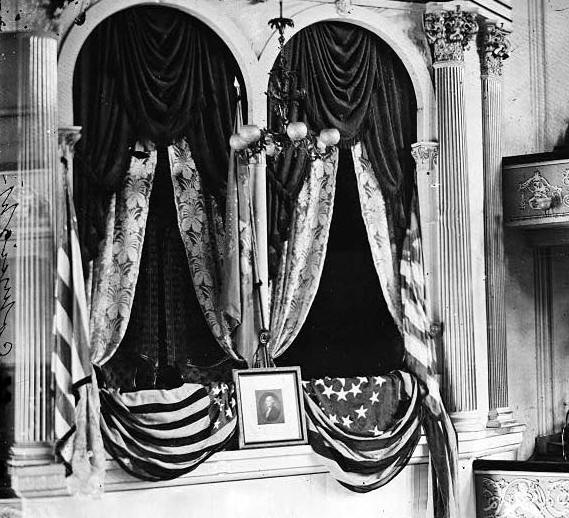

Presidential Box 1865

http://www.sonofthesouth.net/slavery/abraham-lincoln/lincoln-box-ford-theater.htm

Ford’s Theatre Now

http://broadwayworld.com/article/Fords_Theatre_Announces_History_on_Foot_Tours_for_Fall_2009_20090724

Ford’s Theatre sits at 511 10th Street NW, the site originally occupied by the First Baptist Church of Washington which was built in 1833. In 1859, the congregation abandoned the building when they merged with the Fourth Baptist Congregation formed on 13th Street. After a few years of occasional use for music performances, the building gained the interest of John T. Ford, a theatre entrepreneur from Baltimore who arrived in Washington D.C. in 1861. On December 10 of that year, despite controversy from some members of the congregation who predicted “a dire fate for anyone who turned the former house of worship into a theatre,” (Olszewski 7) the church leased the space to Ford. His contract allowed him to rent the building for five years with the promise of an opportunity to buy after that time.

After a brief sublease to George Christy, who ran the building as “The George Christy Opera House,” Ford closed the building and began renovation on February 28, 1862. He invested 10,000 dollars in new construction and remodeling and opened the building three weeks later on March 19 under the name “Ford’s Atheneum” where ticket prices ranged from a quarter to a dollar per seat. The athenaeum was quite successful and won the patronage of many wealthy and famous individuals including Abraham Lincoln whose first visit to the theatre was May 28, 1862 and who said of his experience, “Some people find me wrong to attend the theatre, but it serves me well to have a good laugh with a crowd of people” (Good 3).

Tragedy first struck the theatre on December 30, 1862 when a fire caused by a defective gas meter broke out in the cellar beneath the stage. The fire blazed through everything, leaving only the blackened walls standing. Fortunately no one was killed during the incident, but as Ford was only partially covered by fire insurance, the event left him with an estimated loss of 20,000 dollars.

With a refusal to lose heart, Ford began right away with plans to build a bigger and better theatre at the same site. He wanted to expand the theatre to the north and add an additional wing to the south. He hired James J. Gifford to design and supervise the reconstruction which began in February of 1863. Though Ford had refused help from theatrical colleagues who offered to sponsor benefits to raise the money he lost in the fire, he welcomed the financial backing the project received from wealthy and influential Washington D.C. businessmen. Though the reconstruction met a series of delays due to cave-ins from quicksand beneath the foundation and war-time supply delay problems, the building known as “Ford’s New Theatre” opened on August 27, 1863.

Between 1863 and 1865, the theatre thrived. Many praised the theatre for its magnificent elegance and comfortable ventilation due to the three large hooded ventilators and ten hatches which provided the perfect amount of outside air. Few theatres rivaled Ford’s for these few years. Unfortunately, on April 14, 1865, the theatre became infamous as the location of the assassination of Abraham Lincoln during a performance of Our American Cousin. One spectator recalled the event, “It is impossible to describe the intense excitement that prevailed in the theatre. The audience arose as one person and horror was stamped on every face” (Good 45). In the two seasons before the assassination, the theatre produced 495 evening performances, eight of which were attended by the president including “The Marble Heart” on November 9, 1863 starring none other than John Wilkes Booth, his future assassin.

After the assassination, Ford’s Theatre was guarded by federal troops until July 7, 1865, the day the conspirators were hanged. On July 8, the theatre was returned to Ford only to be seized on July 10 by order of Secretary of War, Edwin M. Stanton. Some time after this, the theatre was leased to the government and then purchased by an act of Congress in 1866.

In 1867, Ford’s Theatre was taken over by the US Army in order to house post-Civil War medical activities of the Army Surgeon General’s Office. The building held an archive of Civil War medical records which were essential for verification of veteran’s pension claims, the Army Medical Museum, editorial offices for preparation of the multi-volume Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion, and the Library of the Surgeon General’s Office. When Army needs outgrew the capacity of the theatre, several units were moved in 1887 to a new building known as the Army Medical Museum and Library, located on the Mall.

In June of 1893, a third tragedy occurred at the former theatre; part of the overloaded interior collapsed, killing 22 and injuring 65 federal troops working in the office of the Adjutant General for compiling official service records of Civil War veterans. Ford’s Theatre was then closed by an order of Congress and was used as public document storage until 1932 when the Lincoln Museum opened inside which currently contains historical artifacts including the derringer John Wilkes Booth used as a murder weapon as well as a replica of the coat Lincoln wore when he was shot.

After public interest in restoring the building to its original condition grew following World War II, preliminary investigation began in 1955 when the National Capital Region prepared an engineering study under Public Law 372, 83d Congress. Additional funds were given under Public Law 86-455, 86th Congress, which authorized the National Park Service to begin with the research and prepare for construction, which was eventually completed in 1967.

Ford’s Theatre reopened in 1968 and according to its current website’s record of past seasons, ran a complete season of shows including a Gala Opening which was featured as a CBS TV special, John Brown’s Body, Comedy of Errors, and She Stoops to Conquer (Ford’s Theatre). Since that time, the theatre produced full seasons of performances until August 2007 when it closed for its most extensive renovation since the 1960s. The theatre reopened in February 2009 fully equipped with new seats, upgraded sound and lighting equipment, improved heating and AC, renovated restrooms, elevators, a new lobby with concessions, a new parlor for special events, and a series of updated stage capabilities. As this year marked the bicentennial of Lincoln’s birth, Ford’s Theatre is working toward becoming a major center for learning where people can examine the events leading up to the death of the 16th president of the United States; the theatre’s mission is “to celebrate the legacy of Abraham Lincoln and to explore the American experience through theatre and education” (Ford’s Theatre) and is now back to running full seasons of performances.

Works Cited

Good, Timothy S., ed. We Saw Lincoln Shot: One Hundred Eyewitness Accounts. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1995. Print.

Ford’s Theatre. History of Medicinie. United States National Library of Medicine National Institutes of Health, 13 Sep. 2006. Web. 16 Oct. 2009. <http://www.nlm.nih.gov/hmd/medtour/ford.html>

Ford’s Theatre. Web. 16 Oct. 2009. < http://www.fordstheatre.org/#>

Olszewski, George J. Restoration of Ford’s Theatre. Washington, D.C.: US. Government Printing Office, 1963. Print.

Recent Comments