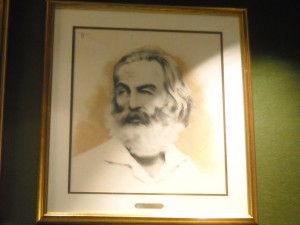

I found Whitman at Riverby Books in downtown Fredericksburg in front of the “Modern Warfare” section

(As if saying goodbye to Whitman wasn’t enough, I had to go and listen to the recording of Ginsberg reading Howl and A Supermarket in California. Thanks, guys 😛 )

As we draw toward the end of the semester, it becomes increasingly important to take a step back from the more particular tasks of uncovering discrepancies between versions of Leaves of Grass, analyzing speakers in various poems, placing Whitman in an historical context, etc. (which can all become consuming as Whitman has so much to offer in these areas) and instead turn our eyes toward Whitman’s legacy, his stamp on the world. In doing so, it is amazing how much larger and completely consuming he becomes, which is a feat for a poet who already “contain[s] multitudes.”

Throughout Andrew C. Higgins’s essay, “The Poet’s Reception and Legacy,” it is made clear that Whitman’s influence was and is everywhere, in every type of artist as well as in those outside of the art world. Among his readers are those like Ginsberg who idolize and welcome him as a catalyst of change and an embracer of beauty, and there are those like T.S. Eliot who wish to extricate Whitman’s political self from his artistic self and deny his influence in the writing world. Despite these polar opposite opinions, it is evident that Whitman’s effect, whatever it may be, did not go unnoticed. He succeeded and succeeds today in reaching people across time and place even from the grave. This can only be attributed to the fact that during his lifetime he refused to conform to the mandates of a dying country and he insisted with all of his might upon a true United States of America.

In pouring over the modern and contemporary poetry we read for this week, I was completely awestruck, not because of the quality and power behind the poetry itself, (though undoubtedly that was part of it) but due to the realization that Whitman’s influence was and is in so many more places than I ever imagined. It is striking to me that a man and poet I knew little of before this semester is in many ways the wellspring of some of my favorite writers – Ginsberg and Rich, for instance. In the third part of Ginsberg’s Howl, he writes, “I’m with you in Rockland / where we hug and kiss the United States under / our bedsheets the United States that coughs all / night and won’t let us sleep” and I cannot think of another line in contemporary poetry where I see and feel Whitman more clearly.

Throughout his life Whitman wrote of this “sick” America that suffered from a lack of unity and a lack of individual love and connection. He fought against the American tendency to grow complacent or violent in the face of such an illness and desired above all else to live in a country that grows in and through each of its members. Whitman’s America lives today in the hospitals with young men and women dying and fighting to live for it. It celebrates the delicate intimacy between “comrades” whether male or female or black or white or rich or poor. Whitman’s America recognizes the poverty and despair that plague it but will not stay silent, will not die out. And Whitman’s America, my America, no matter the age, will not rest until it is truly a nation founded on and for freedom.

All I was able to think about during our trip to Washington D.C. was how much Whitman would be smiling if he knew how devoted we were to uncovering his life’s work. Walking through D.C., a place I have been many times in my life, became a new experience for me as I looked at the area through “Whitman-colored” glasses. Buildings, grassy areas surrounding buildings, even roads became something new that I had never seen before. Things I had previously taken for granted as ordinary became fascinating as I thought about the ways that particular place functioned for Whitman.

Whitman was not merely “under [our] bootsoles” (88), he was everywhere – Lafayette Park, the White House, Department of the Treasury, the Washington Monument, Hotel W and the Red Robin Bar, Constitution Ave., etc. Everywhere we went he was around the corner, or he was the corner:

Being in these places made me a believer in Whitman’s insistency that time need not be as much a disconnector as we would often have it. In “Song of Myself” he writes, “Distant and dead resuscitate, / They show as the dial or move as the hands of me….and I am the clock myself” (63). If Whitman is the clock, then we were keeping time through and by him as we journeyed through D.C.

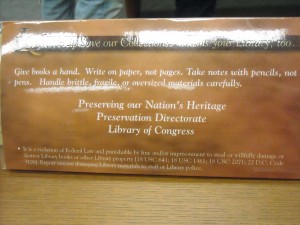

This particularly hit home for me while visitning the Library of Congress, an experience which render even words insufficient descriptors of its impact. As our class greedily gathered around the tables to see handwritten letters, pictures, books, a pen, a watch, a “Calamus” staff, glasses, his haversack, etc. it struck me that Whitman’s historical preservation consciousness was one of, if not the only, reasons why we had the fortune of viewing any of those things. Whitman transcended time; he was aware of his surroundings, his potential legacy, and he succeeded in sharing them with others, even across a century. A group of undergraduate students “oooh”ed and “aahh”ed over artifact after artifact because Whitman cared enough about preserving history to give us that. We have become the ‘gymnastic learners’ he desired and we, in many ways, are forever connected to him because of that.

I thought Whitman would appreciate this sign:

So Sam Krieg, Ben Brishcar, and myself…

upon discovering the existence of a “Walt Wit” belgian-style ale at the Philadelphia Brewing Co. felt we had no other choice but to scurry to Pennsylvania to retrieve it. These are a few images from our journey.

“Afoot and light-hearted [we] took to the open road, / Healthy, free, the [beer] before [us], / The long brown path before [us] leading wherever [we] choose” (297)

Whitman AND Lincoln told us we were on the right path…

The lovely Philadelphia… the quest leaves the interstate…

Whitmanesque graffiti

A slightly disheveled bunch arriving at the brewery.

Our destination!

The side of the bottle reads, “The American poet Walt Whitman once portrayed a sunset over Philadelphia as,’…a broad tumble of clouds, with much golden haze and profusion of beaming shaft and dazzle.’ Pour yourself a bottle of Walt Wit Belgian Style White Ale and see what he was talking about . A pinch of spice and a whisper of citrus lend complexity to this fragrant, satisfying ale.

Walt Wit – it’s transcendentally delicious.”

As other people have been posting a lot of pictures of places themselves, I thought it would be interesting to post a few that had our class interacting with and existing in them. A lot of my thinking about the field trips have been in how much going to the same places Whitman himself occupied and wrote about was fulfilling his vision that everyone is connected through space and time through place.

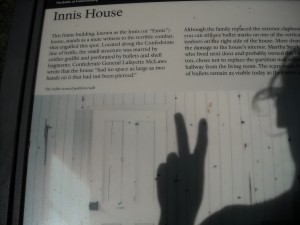

These are both the lovely Meghan Edwards examing the bullet holes at the Innis House.

My attempt at artistry: The information sign at the Innis House. The house was probably owned by Martha Stephens who refused to leave her home (the Stephens’ House marked by the foundation nearby the Innis House) during the battle. She provided drink to both Union and Confederate soldiers, an act of promoting peace between the two sides during a time of war.

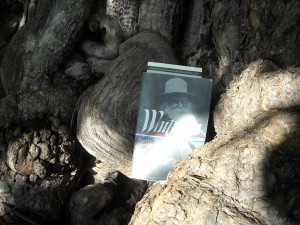

“Leaves of Grass” near the Confederate Cemetery. Looks like a beard to me…

Walt Whitman gang sign? (outside Chatham Manor)

Ouside Chatham toward what was originally the front of the house. The entrance was eventually changed to the garden side, the side we entered before our tour.

Jim Groom examining one of the catawba trees Whitman wrote about in Specimen Days.

Whitman, nestled in the crook of the catawba tree. The passage in the second picture is from “Down at the Front” in Specimen Days. It reads, “Out doors, at the foot of a tree, within ten yards of the front of the house, I notice a heap of amputated feet, legs, arms, hands, &c., a full load for a one-horse cart. Several dead bodies lie near, each cover’d with its brown woolen blanket” (736).

Ben Brishcar & Sam Protich: a new kind of frontispiece (near the catawba trees at Chatham)

The ghost of Whitman? or Erin Longbottom? (looking out from a window at Chatham Manor toward the catawba trees)

Whitman, are you under my Converse-soles too?

Sam Krieg looking out over the Rappahannok a few hundred yards away from the Chatham House.

To focus on one edition of Leaves of Grass without the acknowledgement of the others is reductive to understanding Whitman’s entire vision. Despite the fact that Whitman said of the 1892 edition, “I wish to say that I prefer and recommend this present one, complete, for future printing, if there should be any,” (148) the revolutionary ideas Whitman presented are only fully (or at least more clearly) appreciated when examining all of the texts and how they were changed over time.

Whitman’s dedication to creating one book as opposed to several different volumes is one of his most unique qualities when comparing him to other poets. His desire for Leaves of Grass to become an almost scriptural text rather than simply another collection of poetry is represented in his persistence in revamping and revising the text until he felt it conveyed exactly what people needed to hear in the exact way they needed to hear it (in many ways this can be likened to the varying translations of the Bible). The progression between the 1855 and the “Deathbed” editions, though the text was not extensively altered in content, shows the ways in which the text lived and changed as Whitman lived and changed. There is little to no doubt that Whitman, had he not realized his failing health, would have continued to edit LoG.

After reading Longaker’s “The Last Sickness and the Death of Walt Whitman,” it’s striking to notice how Whitman’s attention to detail prevailed as he cataloged his symptoms, food and medicine intake, amount of sleep, etc., even until his death. This attention is also shown in the slight alterations he made in the versions of LoG across time. Every word counted and he slaved over his texts during each republication in order to make sure each one was in its proper place. Often, he removed imagery that was no longer relevant; for instance, “the camera and plate are prepared, the lady must sit for her daguerreotype” (41) of 1855 is no longer present in 1892 as the use of the daguerreotype diminished at the end of the 1850s. Even slight changes like, “Did you read in the seabooks of the oldfashioned frigate-fight? / Did you learn who won by the light of the moon and stars?” (67) in 1855 to “Would you hear of an old-time sea fight? / Would you learn who won by the light of the moon and stars? / List to the yarn, as my grandmother’s father the sailor told it to me” (227-228) place recognition in the power of the passage of time. This allows the text to insist that events that occur in history do not lose their importance as time distances us from them, a point I believe was at the forefront of his mind at all times during the revision process.

Whitman’s Leaves of Grass is a text that has withstood time because it pays so much attention to time. There are few (if any) other writers in history who put as much effort in maintaining the relevance of one sociopolitical text, especially in the poetic realm, as Whitman did. Therefore, to claim a superior importance of any one version of LoG neglects the importance of the entire vision that a text like LoG does not lose its importance over the years, its reader must simply alter the way he or she approaches it in order to appreciate its power and relevance in the current world. Whitman started that process for his readers as he revised, but passed the torch to them to do the same after he was given to the earth and could no longer aid them.

This is a poem by the poet Ai. I found it particularly interesting to post this week as we are beginning to discuss Walt Whitman’s legacy. I’m interested in other opinions of this poem as, having now studied Whitman fairly extensively, I am not quite sure how I feel about his role in it. And sorry about the double spaces…I couldn’t figure out how to format it better.

Visitation

“Heaven and earth

What else is there?”

said Walt Whitman in your dream,

then he smiled at you

and disappeared,

but you wanted him to come back.

You wanted to tell him that there was more.

there was the hardsell

you had to give yourself to stay alive

HIV positive five years

and counting backward to the day

your other life was stripped

bare of its leaves

at the start of the war of disease

against the body.

You don’t have AIDS,

yet, you know it’s coming

like a train whose whistle

you can hear before you see it.

When you feel the tremors

of internal earthquake,

will you do the diva thing?

Will you Rudolf Nureyev your way on stage,

so ravaged and dazed

you don’t know who you are,

or commit your public suicide in private,

windows open wide

on the other side

where your father, Walt is waiting

to take you in his arms

like a baby returning there on waking,

beside the picnic basket

in the long grass,

where the brittle pages of a book

are turning to the end.

All right, this post might be a bit of a stretch, but bear with me on some ideas I had/have about a difference between the 1855 Leaves of Grass and the 1892 Leaves of Grass, particularly in nuances between the two versions of “Song of Myself.” In the 1855 version of this poem, Whitman names the months and days just as we would name them today: January and February and March, Monday and Tuesday and Wednesday, etc. However, in the 1892 version, Whitman rejects the use of these common names and instead replaces them with First-month, Second-month, First-day, Second-day, and so on. In no place in the 1892 version of “Song of Myself” can be located the actual name of a month or day.

After noticing this, I started to poke around about the etymology and history of the months and days. Although it seems that much is unknown about the history of these names, the most well-accepted origin and explanation is that the calendar as well as these divisions was established by the late Roman Empire, furthered by the Christian church, and widely assimilated into standardized use by the British Empire. The days were originally named after Greek (and later substituted for Roman) gods. Later, Germanic groups substituted similar gods for the Roman gods until the list became something like, Sun’s day, Moon’s day, Tiu’s day, Woden’s day, Thor’s day, Freya’s day, and Saturn’s day. The Christian church maintained and encouraged the division of the seven day week as biblically, God created the world in six days and rested on the seventh, the Jewish holy day the Sabbath, which is observed on Saturday.

As for the months of the year, the calendar used today is often referred to as the “Christian calendar” although it was developed in pre-Christian Rome. There are two main versions of the Christian calendar: the Julian and the Gregorian calendars. Before this, the original Roman calendar had ten months: Martius, Aprilis, Maius, Junius, Quintilis, Sextilis, September, October, November, and December. The second king of Rome, Numa Pompilius, added January, or Januarius, and February or Februarius around 700 BCE. The names January, March, April, May, and June were, like the days of the week, developed from the names of gods. The names of the other months developed as follows: February stems from Februa, the Roman festival of purification, July, which Julius Caesar named after himself, August, which Augustus Caesar named after himself, and September, October, and December which (less creatively) simply mean seventh month, eighth month, ninth month, and tenth month, after their original placements on the Roman calendar.

Head spinning yet? Good, mine too. Now, for where I’m going with all of this; I find it fascinating that Whitman would reject the use of these common names in his final version of “Song of Myself.” Perhaps I’m overanalyzing the heck out of this, but I feel that if I am right about this conscious effort to change the names, a probable motive could be Whitman’s attempt to wipe the slate clean of all history that America took from Europe, even something as seemingly mundane as day and month names. It could also be a try at truly encouraging religious freedom. By rejecting the use of one historical religion (whether the polytheistic Roman faith or the monotheistic Christian one) as a governance over society in any way, even in a mere commonly assimilated set of names, Whitman opens the door wide to a nation of true religious tolerance. In naming the days and months by numbers instead of by gods or by Christian systems, Whitman is sets at accomplishing this little by little.

Furthermore, God seems to play a very different role for Whitman in the 1892 version and thereby furthers my argument that Whitman is truly attempting widespread religious freedom. In many of the places where God was aiding Whitman in the 1855 version, He is either completely removed or replaced by something or someone else. For instance, in the 1855 “Song of Myself,” Whitman writes, “As God comes a loving bedfellow and sleeps at my side all night and close on the peep of the day,” (29) but in 1892 the passage is altered to, “As the hugging and loving bed-fellow sleeps at my side through the night, and withdraws at the peep of the day with stealthy tread” (191). Similarly in 1855 he writes, “I visit the orchards of God and look at the spheric product” (63) and in 1892, “I visit the orchards of spheres and look at the product.” Removing God in these ways, as well as reshaping Him throughout the text allows Whitman to, again, open up LoG to become something relatable to all individuals, no matter what faith or cultural background. It is not so much that I think Whitman has altered his beliefs about religion as it is that I believe he is attempting to do a better job of disallowing the way he was religiously educated to interfere with the true religious freedom America was supposed to be founded on.

If you are interested in information about the days and calendar, I got a lot of my information from these sites:

http://www.crowl.org/Lawrence/time/months.html

http://www.crowl.org/Lawrence/time/days.html

http://www.webexhibits.org/calendars/year-history.html

http://www.webexhibits.org/calendars/week.html#anchor-origin

Recent Comments