On May 31, 1889, Walt Whitman’s seventieth birthday, 2,209 people were killed when the South Fork Dam failed, sending a wall rushing water and debris cascading into the riverside town of Johnstown, Pennsylvania. It was the largest civilian loss of life in American history up to that time (McCullough, 4). It was also one of the first major disaster relief efforts led by the American Red Cross, under the direction of Clara Barton.

The dam, located 14 miles upstream from Johnstown, held back the artificial Lake Conemaugh, a canal basin that the state never completed due to emergence of the railroad. The lake was sold to private interests and became part of the South Fork Hunting and Fishing Club, playground for wealthy Pittsburgh steel executives. The owners had made questionable modifications to the dam, lowering it in order to build a road on top of it. These modifications, along with poor maintenance and record rainfall were blamed for the dam’s failure.

On May 30, 1889, a storm swept over western Pennsylvania from the Midwest dumping six to ten inches of rain over western Pennsylvania. The following day, as Lake Conemaugh swelled, an impromptu team of men tried to clear debris from the dam spillway. At 3:10, the dam burst and the lake spilled into the narrow Little Conemaugh River, picking up houses, farm animals, people, barns, bridges, barbed wire, and train cars as it moved downstream. By the time the water and debris reached Johnstown, eyewitnesses reported it was 40 feet high and a half-mile wide (Loving, 116). At least 80 people died in the fires the followed as the debris that had piled up behind a rail bridge began to burn. Four square miles of Johnstown were completely destroyed. 1600 homes were lost. 2209 people, including 396 children and 99 entire families perished.

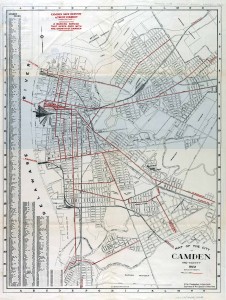

By the evening, the storm had reached Camden, where Walt Whitman and his supporters were celebrating the poet’s seventieth birthday party at Morgan’s Hall. Whitman was deeply saddened by the disaster. He found it ironic that the tragedy occurred during the height of his birthday celebration (Reynolds, 573).

Horace Traubel recorded Whitman’s remarks six days after flood.

8 P.M. Went down to W.’s with Harned, finding W. sitting in parlor at the window. Had but a little time before returned from his outing. Talked directly of the Johnstown affair. “It seems to hang over us all like a cloud,” he said—”a dark, dark, dark cloud.” And then he asked: “Do you think this Cambria matter interferes at all with the passage of the mails? We all live in Cambria County now (Traubel, 264).

Whitman wrote “A Voice from Death” about the flood victims. The poem was published in the New York World on June 7, 1889, only a week after the flood. Whitman was paid $25.

With sudden, indescribable blow–towns drown’d–humanity by

thousands slain,

The vaunted work of thrift, goods, dwellings, forge, street, iron bridge,

Dash’d pell-mell by the blow–yet usher’d life continuing on,

(Amid the rest, amid the rushing, whirling, wild debris,

A suffering woman saved–a baby safely born!)

Although I come and unannounc’d, in horror and in pang,

In pouring flood and fire, and wholesale elemental crash, (this

voice so solemn, strange,)

I too a minister of Deity.

Yea, Death, we bow our faces, veil our eyes to thee,

We mourn the old, the young untimely drawn to thee,

The fair, the strong, the good, the capable,

The household wreck’d, the husband and the wife, the engulfed forger

in his forge,

The corpses in the whelming waters and the mud,

The gather’d thousands to their funeral mounds, and thousands never

found or gather’d.

Then after burying, mourning the dead,

(Faithful to them found or unfound, forgetting not, bearing the

past, here new musing,)

A day–a passing moment or an hour–America itself bends low,

Silent, resign’d, submissive.

War, death, cataclysm like this, America,

Take deep to thy proud prosperous heart.

E’en as I chant, lo! out of death, and out of ooze and slime,

The blossoms rapidly blooming, sympathy, help, love,

From West and East, from South and North and over sea,

Its hot-spurr’d hearts and hands humanity to human aid moves on;

And from within a thought and lesson yet.

Thou ever-darting Globe! through Space and Air!

Thou waters that encompass us!

Thou that in all the life and death of us, in action or in sleep!

Thou laws invisible that permeate them and all,

Thou that in all, and over all, and through and under all, incessant!

Thou! thou! the vital, universal, giant force resistless, sleepless, calm,

Holding Humanity as in thy open hand, as some ephemeral toy,

How ill to e’er forget thee!

For I too have forgotten,

(Wrapt in these little potencies of progress, politics, culture,

wealth, inventions, civilization,)

Have lost my recognition of your silent ever-swaying power, ye

mighty, elemental throes,

In which and upon which we float, and every one of us is buoy’d.

Work Cited

Loving, Jerome “The Political Roots of Leaves of Grass.” A Historical Guide to Walt Whitman. Ed. David S. Reynolds.New York, NY: Oxford UP (2000): 116-117. Google Books. Web. 20 Oct. 2009.

McCullough, David G. The Johnstown Flood. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1967. 4-81. Google Books. Web. 20 Oct. 2009.

Reynolds, David S. Walt Whitman’s America: A Cultural Biography. New York: Vintage Books, 1995. Print.

Traubel, Horace. With Walt Whitman in Camden Volume 5. Ed. Gertrude Traubel. Carbondale: U of Southern Illinois P, 1964. Google Books. Web. 21 Oct. 2009.

Whitman, Walt. “A Voice from Death.” Whitman Poetry & Prose. Library of America College Editions, 1996. Print.