Cyprian Norwid

Cyprian Norwid | |

|---|---|

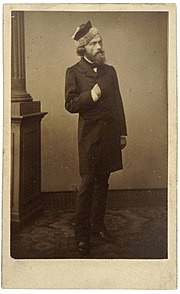

Cyprian Kamil Norwid in 1871 | |

| Born | Cyprian Konstanty Norwid 24 September 1821 Laskowo-Głuchy near Warsaw, Congress Poland |

| Died | 23 May 1883 (aged 61) Paris, France |

| Occupation | Poet, essayist |

| Language | Polish |

| Nationality | Polish |

| Period | 1840-1883 |

| Genre | Romanticism, Modernism |

| Notable works | Vade-mecum Promethidion Ad leones! |

| Relatives | Ludwik |

| Signature | |

| |

Cyprian Kamil Norwid (Polish pronunciation: [ˈt͡sɨprjan ˈnɔrvit]; 24 September 1821 – 23 May 1883), a.k.a. Cyprian Konstanty Norwid, was a Polish poet, dramatist, painter, sculptor, and philosopher.

Norwid's original, nonconformist style was not appreciated in his lifetime. Partly due to this, he was excluded from high society. His work was rediscovered and appreciated, only after his death, by the Young Poland movement of the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries.

He is now considered one of the four most important Polish Romantic poets, though scholars still debate whether he is more aptly described as a late romantic or an early modernist.

Norwid led a tragic, often poverty-stricken life. He experienced mounting health problems, unrequited love, harsh critical reviews, and increasing social isolation. For most of his life he lived abroad, chiefly in London, dying in Paris.

Life[edit]

Youth[edit]

Cyprian Norwid was born on 24 September 1821 into a Polish–Lithuanian minor noble family bearing the Topór coat of arms,[1]: 3 [2]: v in the Masovian village of Laskowo-Głuchy near Warsaw,[3]: 3 His father was a minor government official.[2]: v One of his maternal ancestors was the Polish King John III Sobieski.[2]: v [4]: 160

Cyprian Norwid and his brother Ludwik were orphaned early. His mother died when Cyprian was four years old, and in 1835 his father died, leaving 14-year old Norwid an orphan.[2]: v [5] For most of their childhood, Cyprian and his brother were educated at Warsaw schools.[5] In 1836 Norwid interrupted his schooling (not having completed the fifth grade)[2]: v–vi and entered a private school of painting, studying under Aleksander Kokular and Jan Klemens Minasowicz.[2]: vi [5] His incomplete formal education forced him to become an autodidact, and despite his lack of much formal education he succeeded at this, learning a dozen languages.[2]: viii [6]: 28 [7]: 268

His first foray into the literary sphere occurred in the periodical Piśmiennictwo Krajowe, which published his first poem, Mój ostatni sonet (My Last Sonnet), in issue 8, 1840.[1]: 11 [8]: 34 That year he published ten poems and one short story.[2]: vi His early poems were well received by critics and he became a welcome guest at the literary salons of Warsaw; at that time he was often described as a "dandy" and a "rising star" of the young generation fo Polish poets.[7]: 268–269 [2]: vii–viii In 1841-1842 he travelled through the Congress Poland with Władysław Wężyk.[5][2]: ix

Europe[edit]

In 1842 Norwid received inheritance funds as well as a private scholarship to study sculpture and left Poland, never to return.[2]: ix [5][7]: 269 First he went to Dresden in Germany. He later also visited Venice and Florence in Italy; in Florence he signed up for a course in sculpture at the Accademia di Belle Arti di Firenze.[5] His visit to Verona resulted in a well-received poem W Weronie (In Verona) published several years later.[2]: x After he settled in Rome in 1844, where for several years he became a regular at Antico Caffè Greco,[7]: 269 his fiancée Kamila broke off their engagement.[9] Later he met Maria Kalergis, née Nesselrode; they became acquaintances, but his courtship of her, and later, of her lady-in-waiting, Maria Trebicka, ended in failure.[5] The poet then travelled to Berlin, where he participated in university lectures and meetings with local Polonia. It was a time when Norwid made many new social, artistic and political contacts. In Berlin he was arrested due to a misunderstanding, and his short stay in prison resulted in partial deafness.[5] At that time he also lost his Russian citizenship.[7]: 269 After being forced to leave Prussia in 1846, Norwid went to Brussels.[5] During the European Revolutions of 1848, he stayed in Rome, where he met fellow Polish intellectuals Adam Mickiewicz and Zygmunt Krasiński.[5]

During 1849–1852, Norwid lived in Paris, where he met fellow Poles Frédéric Chopin and Juliusz Słowacki,[5] as well as other emigree artists such as Russians Ivan Turgenev and Alexander Herzen, and other intellectuals such as Jules Michelet (many at Emma Herwegh's salon).[10]: 28 [11]: 816 Financial hardship, unrequited love, political misunderstandings, and a negative critical reception of his works put Norwid in a dire situation. He lived in poverty, sometimes forced to work as a simple manual laborer.[7]: 269 He also suffered from progressive blindness and deafness, but still managed to publish some content in the Polish-language Parisian publication Goniec polski and similar venues[7]: 269 [12][13] (1849 saw several of his poems published, those included among others his Pieśń społeczna, Social Song).[11]: 816 Some of his notable works from that period include poem Bema pamięci rapsod żałobny, drama Zwolon and the philosophical poem-treaty about the nature of art, Promethidion.[5][14] Promethidion, a long treatise on aesthetics in verse, has been called "the first important piece of Norwid's writing".[15]: 814 It was, however, not well received by contemporary critics.[16]: 816 The year 1851 saw him finishing the manuscripts for the dramas Krakus and Wanda[17][18] and the poem Bema pamięci żałobny-rapsod (A Funeral Rhapsody in Memory of General Bem).[19][20]

U.S.A.[edit]

Norwid decided to emigrate to the United States of America in the Fall of 1852, receiving some sponsorship from Wladyslaw Zamoyski.[21]: 190 On 11 February 1853 he arrived in New York City aboard the Margaret Evans, and he held a number of odd jobs there, including at a graphics firm.[22] He was involved in the creation of the memorial album of the Crystal Palace Exhibition and the Exhibition of the Industry of All Nations.[7]: 269 [15]: 816 By autumn, he learned about the outbreak of the Crimean War. This, as well as his disappointment with America, which he felt lacked "history", made him consider a return to Europe, and he wrote to Mickiewicz and Herzen, asking for their assistance.[7]: 269 [22]

Back in Paris[edit]

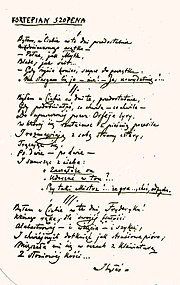

During April 1854, Norwid returned to Europe with Prince Marceli Lubomirski. He lived in England with Krasiński's help he was finally able to return to Paris by December that year.[22] With his artistic work revived, Norwid was able to publish several works, such as the poem and Quidam. Przypowieść (Quidam. A Story, 1857) and stories collected in Czarne kwiaty. Białe kwiaty (Black Flowers. White Flowers), published in Czas in 1856-1857.[5][15]: 815–816 [23] He gave a well-received series of six lectres on Juliusz Słowacki in 1860, published the next year.[15]: 816 1862 saw the publication of some of his poems in an anthology Poezje (Poems) at Brockhaus in Leipzig .[a][15]: 816 [7]: 269 He took a very keen interest in the outbreak of the January Uprising in 1863. Although he could not participate personally due to his poor health, Norwid hoped to personally influence the outcome of the event.[24] His 1865 Fortepian Szopena (Chopin's Piano) is seen as one of his works reactign to the January Uprising.[25][10]: 54–58 The poem's theme is the Russian troops' 1863 defenestration of Chopin's piano from the music school Norwid attended in his youth.[26][27][28]: 514–515

He kept on writing, but with little recognition. He grew to accept this, and even wrote in one his works that "the sons pass by this writing, but you, my distant grandchild, will read it... when I'll be no more" (Klaskaniem mając obrzękłe prawice..., The Hands Were Swollen by Clapping..., 1858).[15]: 814

In 1866, the poet finished his work on Vade-mecum, a vast anthology of verse. However, despite his greatest efforts it was unable to be published until decades later.[5][29]: 375–378 [30] One of the reasons for this included Prince Władysław Czartoryski failing to grant the poet the loan he had promised. In subsequent years, Norwid lived in extreme poverty and suffered from tuberculosis.[10]: 60 During the Franco-Prussian War of 1870 when many of his friends and patrons were distracted with the global evens, he has been starving and his health further deteriorated.[15]: 816 Material hardships did not stop him from writing, in 1869 he wrote Rzecz o wolności słowa (A Poem About the Freedom of the Word), a long treatise in verse about the history of words., which was well received at that time. The next year he wrote Assunta, a poem reflecting his views on Christian love, which Christopher John Murray called Norwid's "most successful narrative poem".[15]: 815 [31] Those years also saw him write three more plays, comedies Aktor. Komediodrama (Actor. Comedy-drama, 1867), Za kulisami (Behind the Scenes, 1865-1866), and Pierścień Wielkiej Damy (The Ring of a Grand Lady, 1872), which Murray praised as Norwid's "real genre within the theater".[15]: 815 The latter play became Norwid's most frequently prefermed theater piece, although like many of his works, it gained recognition long after his death (published in print in 1933, and staged in 1936).[15]: 815 [32][33]: 291 [b]

In 1877 his cousin, Michał Kleczkowski relocated Norwid to the St. Casimir's Institute nursing home (Œuvre de Saint Casimir) on the outskirts of Paris in Ivry.[5][15]: 816 [34] That location, run by Polish nuns, was home to many destitute Polish emigrants.[5][7]: 270 There, Norwid was befriended by Teodor Jełowicki who also gave him material support.[35]: 276 Some of his final works include a comedy play Miłość czysta u kąpieli morskich (Pure Love at Sea Baths, 1880), the philosophical treatesie Milczenie (Silence, 1882), and novels Ad leones! (written c. 1881–83), Stygmat (Stigmata, 1881–82) and Tajemnica lorda Singelworth (The Secret of Lord Singelworth, 1883).[36] Throughouthis life, he also wrote many letters, over a 1,000 of which survived to be studied by scholars.[5]

During the last months of his life, Norwid was weak and bed-ridden. He frequently wept and refused to speak with anyone. He died in the morning of 23 May 1883.[5] Jełowicki and Kleczkjowski personally covered the burial costs, and Norwid's funeral was also attended by Franciszek Duchiński and Mieczysław Geniusz.[37] After 15 years the funds to maintain his grave dried out and his body was moved to a mass grave of Polish emigrants.[5]

Themes and views[edit]

Norwid's early style could be classfied as belonging within the romanticism tradition, but it soon evolved beyond it.[5][15]: 814 [38]: 5 Some scholars consider Norwid to represent late romanticism, others see him as an early modernist.[5][15]: 814 Polish literary critics, Przemysław Czapliński, Tamara Trojanowska and Joanna Niżyńska described Nowrid as "a 'late child' and simultaneously a great critic of Romanticism" and "the first post-Romantic poet [of Poland]".[39]: 68 Danuta Borchardt who translated some of Norwid's poems to English wrote that "Norwid's work belongs to late Romanticism. However, he was so original that scholars cannot pigeonhole his work into any specific literary period".[38]: 5 Czesław Miłosz wrote that "[Norwid] preserved complete independence from the literary currents of the day".[7]: 271 This could be seen in his short stories, which went against the common trend in the 19th century to write realistic prose and instead are more aptly described as "modern parables".[40]: 279

Critics and literary historians eventually concluded that during his life, Norwid was rejected by his contemporaries as his style was too unique compared to then-prevailing themes (romanticism and positivism) works were also not aligned with the political views of the emigre Poles.[5][41][42] His style was criticzed for "being obscure and overly cerebral" and having a "jarring syntax".[38]: 5 [7]: 268 A number of scholars refer to his works, in this context, as "dark", meaing "weird" or "difficult to understand".[43]

While Norwid did not ceate neologisms, he would change words creating new variations of existing language, he also experimented with synatax and punctuation, for example through the use of hyphenated words, which is not common in Polish language. Much of his work is rhymed, although some is seen as a precursor to free verse that later became more common in Polish poetry.[38]: 5 Miłosz noted that Norwid was "against aestheticism", and that he aimed to "break the monotony... of the syllabic pattern", purposefully making his verses "roughhewn".[40]: 271

While he displays a Romantic admiration for heroes, he almost never addresses the concept of romantic love.[15]: 814 Norwid attempted to start new types of literary works, for example "high comedy" and "bloodless white tragedy". His works are considered to be deeply philosophical and utilitarian, and he rejected "art for art's sake".[5][40]: 279–280 He is seen as a harsh critic of the Polish society as well as of mass culture. His portrayal of women characters has been praised as more developed than that of many of his contemporaries, whose female characters were more one-dimensional.[5] Borchardt summarized his ideas as "that of a man deeply disressed by and disappointed in mankind, yet hopeful of its eventual redemption".[38]: 5 Miłosz pointed out that Norwid used irony (comparing his use of it to Jules Laforgue or T. S. Eliot), but it was "so hidden within symbols and parables" that it was often missed by most readers. He also argued that Norwid is "undoubtedly... the most 'intellectual' poet to ever write in Polish", although lack of audience has "permitted him to indulge in such a torturing of the language that some of his lines are hopelessely obscure".[40]: 271–272, 275, 278

His works featured more than purely Polish context, employing pan-European, Greco-Christian symbology.[15]: 814 They also endorsed orthodox Christian, Roman Catholic views;[5] in fact Christopher John Murray argues that one of his major themes was "the state and future of Christian civilization".[15]: 814 Miłosz similarly noted that Norwid did not reject civilization, although he was critical of some of its aspects; he saw history as a story of progress "to make martyrdom unnecessary on Earth".[40]: 272–275 Historical references are common in Norwid's work, which Miłosz describe as affected by "intense historicism".[40]: 279 Norwid's stay in America also made him a supporter of the abolitionist movement, and in 1859 he wrote two poems about John Brown Do obywatela Johna Brown (To Citizen John Brown) and John Brown.[7]: 269 [44] Another recurring motif in his work was the importance of labor, particularly in the context of artistic work, with his discussions of issues such as how should artists be compensated in the capitalistic society - although Miłosz noted that Norwid was not a socialist.[5][15]: 814 [40]: 273–274

Norwid's work has also been treated as deeply philosophical.[45][46] Miłosz also noted that some consider Norwid to be a philosopher more than an artist, and indeed Norwid has inspired, among others, philosophers such as Stanisław Brzozowski. Nonetheless, Miłosz disagrees with that notion, quoting Mieczysław Jastrun who wrote that Norwid was "first of all, an artist, but an artist for whom the most interesting material is thought, reflection, the cultural experience of mankind",.[40]: 280

Legacy and commemoration[edit]

Following his death, many of Norwid's works were forgotten; it was not until the early 20th century, in the Young Poland period, that his finesse and style was appreciated.[7]: 266 [38]: 6 At that time, his work was discovered and popularised by Zenon Przesmycki, a Polish poet and literary critic who was a member of the Polish Academy of Literature. Przesmycki started republishing Norwid's works c. 1897, and created an enduring image of him, one of "the dramatic legend of the cursed poet".[5][7]: 270 [47]

Norwid's "Collected Works" (Dzieła Zebrane) were published in 1966 by Juliusz Wiktor Gomulicki, a Norwid biographer and commentator. The full iconic collection of Norwid's work was released during the period 1971–76 as Pisma Wszystkie ("Collected Works"). Comprising 11 volumes, it includes all of Norwid's poetry as well as his letters and reproductions of his artwork.[48][49]

On 24 September 2001, 118 years after his death in France, an urn containing soil from the collective grave where Norwid had been buried in Paris' Montmorency cemetery was enshrined in the "Crypts of the Bards" at Wawel Cathedral. There, Norwid's remains were placed next to those of fellow Polish poets Adam Mickiewicz and Juliusz Słowacki. The cathedral's Zygmunt Bell, heard only when events of great national and religious significance occur, resounded loudly to mark the poet's return to his homeland. During a special Thanksgiving Mass held at the cathedral, the Archbishop of Kraków, cardinal Franciszek Macharski said that 74 years after the remains of Juliusz Slowacki were brought in, again the doors of the crypt of bards have opened "to receive the great poet, Cyprian Norwid, into Wawel's royal cathedral, for he was an equal of kings".[50]

In 2021, on the 200th anniversary of Norwid's birth, brothers Stephen and Timothy Quay produced a short film Vade-mecum about the poet's life and work in an attempt to promote his legacy among foreign audiences.[51][52]

Norwid is often considered the fourth more important poet of the Polish romanticism, and called the Fourth of the Three Bards.[39]: 68 In fact, some literary critics of the late 20th-century Poland were skeptical as to the value of Krasiński's work and considered Norwid to be the Third bard instead of Fourth.[53][54]: 276 [55]: 8 Well known in Poland, and a part of Polish school's cirricula, Norwid nonetheless remains obscure in English-speaking world.[42] He has been praised as the best poet of the 19th century by Joseph Brodsky and Tomas Venclova.[56] Miłosz notes he has become recognized as a "precusor of modern Polish poetry".[7]: 268

The life and work of Norwid have been subject to a number of scholarly treatments. Those include the English-language collection of essays about him, published after a 1983 conference held to commemorate century since his death (Cyprian Norwid (1821-1883): Poet - Thinker - Craftsman, 1988) [57] or monographs such as Jacek Lyszczyna's (2016) Cyprian Norwid. Poeta wieku dziewiętnastego (Cyprian Norwid. A Poet of the Nineteenth Century).[6] An academic journal dedicated to the study of Norwid, Studia Norwidiana, has been published since 1983.[58]

Works[edit]

Norwid authored numerous works, from poems, both epic and short, to plays, short stories, essays and letters. During his lifetime, according to Miłosz[7]: 269 and Murray,[11]: 816 he published only one large volume of poetry (in 1862)[a] (although Borchardt mentions another volume from 1866[38]: 6 ). Borchardt considers his major works to be Vade-mecum, Promethidion and Ad leones!.[38]: 6 Miłosz acknowledged Vade-mecumas Norwid's most influential work, but also praised his earlier Bema pamięci rapsod żałobny as one of Norwid's most famous poem.[40]: 272–275

Norwid's most extensive work, Vade mecum, written between 1858 and 1865, was first published a century after his death.[30] Some of Norwid's works have been translated into English by Walter Whipple and Danuta Borchardt in the United States of America, and by Jerzy Pietrkiewicz and Adam Czerniawski in Britain.[59]

In English[edit]

- The Larva[60]

- Mother Tongue (Język ojczysty)[61]

- My Song[62]

- To Citizen John Brown (Do obywatela Johna Brown)[63]

- What Did You Do to Athens, Socrates? (Coś ty Atenom zrobił Sokratesie...)[64]

- In Verona (W Weronie) translated by Jarek Zawadzki[65]

In Polish[edit]

- Fortepian Szopena[66]

- Assunta (1870)

In Bengali[edit]

- Poems of Cyprian Norwid (কামিল নরভিদের কবিতা) translated into Bengali language by Annonto Uzzul.[67]

Bibliography[edit]

- Jarzębowski, Józef. Norwid i Zmartwychstańcy. London: Veritas, 1960. ("Norwid and The Resurrectionists")

- Kalergis, Maria. Listy do Adama Potockiego (Letters to Adam Potocki), edited by Halina Kenarowa, translated from the French by Halina Kenarowa and Róża Drojecka, Warsaw, 1986.

See also[edit]

- Cyprian Norwid Theatre

- List of Polish poets

- Parnassism

- Stanisław Wyspiański, another Polish writer also called the Fourth Bard of Poland

References[edit]

Notes[edit]

a. ^ The volume was published in 1862 but with a printed date of 1863.[68]

b. ^ Miłosz noted that Norwid's plays are permormed in Poland occasionally but "they are difficult to stage on account of their reliance upon innuendos and their deliberate avoidance of blatant effects. They could more aptly be called dramatic poems".[7]: 279

Citations[edit]

- ^ a b Gomulicki, Juliusz W. (1965). Wprowadzenie do biografii Norwida (in Polish). Państwowy Instytut Wydawniczy.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Norwid, Cyprian Kamil; Braun, Kazimierz (2019). "Wstęp". Cztery dramaty (in Polish). Zakład Narodowy im. Ossolińskich. ISBN 978-83-66267-10-7.

- ^ Gomulicki, Juliusz W. (1976). Cyprian Norwid: przewodnik po życiu i twórczości (in Polish). Państ. Instytut Wydawniczy.

- ^ Król, Marcin (1985). Konserwatyści a niepodległość: studia nad polską myślą konserwatywną XIX wieku (in Polish). Instytut Wydawniczy Pax. ISBN 978-83-211-0580-2.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa "Norwid Cyprian Kamil". Encyklopedia PWN (in Polish). Retrieved 2023-03-08.

- ^ a b Lyszczyna, Jacek (2016). Cyprian Norwid. Poeta wieku dziewiętnastego (in Polish). Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Śląskiego. ISBN 978-83-8012-878-1.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Milosz, Czeslaw (1983-10-24). The History of Polish Literature, Updated Edition. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-04477-7.

- ^ Sudolski, Zbigniew (2003). Norwid: opowieść biograficzna (in Polish). Ancher. ISBN 978-83-85576-29-7.

- ^ Stanisz, Marek (2006). "Norwid u progu XXI wieku". Studia Norwidiana (in Polish) (24–25): 244–265. ISSN 0860-0562.

- ^ a b c Gömöri, George (1974). Cyprian Norwid. Twayne Publishers. ISBN 978-0-8057-2656-5.

- ^ a b c Murray, Christopher John (2013-05-13). "Norwid, Cyprian Kamil 1821-1883". Encyclopedia of the Romantic Era, 1760–1850. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-45578-1.

- ^ Zehnder, Christian (2021). "Najmniejsza powszechność. O Norwidowskiej skali aktywizmu". Pamiętnik Literacki. Czasopismo kwartalne poświęcone historii i krytyce literatury polskiej (in Polish). 112 (3): 143–162. doi:10.18318/pl.2021.3.8. ISSN 0031-0514. S2CID 245260831.

- ^ CORLISS, FRANK J. (1977). "Review of Cyprian Norwid, George Gömöri". The Polish Review. 22 (4): 98–101. ISSN 0032-2970. JSTOR 25777532.

- ^ "Norwid Cyprian, Bema pamięci rapsod żałobny - Materiały dodatkowe – galeria wiedzy Wydawnictwa Naukowego PWN". encyklopedia.pwn.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 2023-03-25.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Murray, Christopher John (2013-05-13). "Norwid, Cyprian Kamil 1821-1883". Encyclopedia of the Romantic Era, 1760–1850. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-45578-1.

- ^ Murray, Christopher John (2013-05-13). "Norwid, Cyprian Kamil 1821-1883". Encyclopedia of the Romantic Era, 1760–1850. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-45578-1.

- ^ Dąbrowicz, Elżbieta (2017). "Rzeczy, które ranią. O Krakusie Cypriana Norwida". Białostockie Studia Literaturoznawcze (in Polish). 10 (10): 103–121. doi:10.15290/bsl.2017.10.07. ISSN 2082-9701.

- ^ Nurzyńska, Agnieszka (2017-02-08). "Wanda Cypriana Norwida Wobec Tradycji Staropolskiej". Colloquia Litteraria. 20 (1): 229. doi:10.21697/cl.2016.1.15. ISSN 1896-3455.

- ^ Bodusz, Marek (2008-06-15). ""Ołtarz" Zbigniewa Herberta - wiersz, styl, semantyka". Przestrzenie Teorii (in Polish) (9): 193–203. doi:10.14746/pt.2008.9.14. ISSN 2450-5765.

- ^ Nowak-Wolna, Krystyna (2009). "Cypriana Norwida slowo i druk". Stylistyka (in Polish) (XVIII): 113–139. ISSN 1230-2287.

- ^ Inglot, Mieczysław (1991). Cyprian Norwid (in Polish). Wydawn. Szkolne i Pedagogiczne. ISBN 978-83-02-03432-9.

- ^ a b c GÖMÖRI, GEORGE (2001). "Cyprian Norwid's Image of England and America". The Polish Review. 46 (3): 271–281. ISSN 0032-2970. JSTOR 25779271.

- ^ "Norwid Cyprian, Czarne kwiaty, Białe kwiaty - Materiały dodatkowe – galeria wiedzy Wydawnictwa Naukowego PWN". encyklopedia.pwn.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 2023-03-25.

- ^ Niewczas, Łukasz (2016). "Colloquia Norwidiana XIII: Norwid and the January Uprising". Studia Norwidiana (34EV): 297–303. ISSN 0860-0562.

- ^ Esq, Justin Wintle; Wintle, Justin (2021-12-24). Makers of Nineteenth Century Culture. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-85363-3.

- ^ Niewczas, Łukasz (2018-12-30). "Norwid's Visual Metaphors on the Example of "Fortepian Szopena" ("Chopin's Pianoforte")". Colloquia Litteraria. 2 (4). doi:10.21697/cl.2018.2.6. ISSN 1896-3455. S2CID 70217528.

- ^ Zubel, Marla (2019). "Remembering the Global '60s: A View from Eastern Europe". Cultural Critique. 103: 36–42. doi:10.5749/culturalcritique.103.2019.0036. ISSN 0882-4371. JSTOR 10.5749/culturalcritique.103.2019.0036.

- ^ Jakubowski, Jan Zygmunt; Pietrusiewiczowa, Jadwiga (1979). Literatura polska od średniowiecza do pozytywizmu (in Polish) (Wyd. 4 ed.). Warszawa: Państwowe Wydaw. Naukowe. ISBN 83-01-00201-8. OCLC 69343086.

- ^ Norwid, Cyprian (1971). Gomulicki, Juliusz W. (ed.). Cyprian Kamil Norwid: Pisma wszystkie (in Polish). Vol. 2. Państwowy Instytut Wydawniczy.

- ^ a b "Norwid Cyprian, Vade-mecum - Materiały dodatkowe – galeria wiedzy Wydawnictwa Naukowego PWN". encyklopedia.pwn.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 2023-03-25.

- ^ Doktór, Roman (1998). "Przyczynek do genezy Assunty Cypriana Norwida". Roczniki Humanistyczne (in Polish). 46 (1): 223–230.

- ^ Samsel, Karol (2019). ""Pierścień Wielkiej-Damy" Cypriana Norwida jako dramat interfiguralny". Pamiętnik Literacki. Czasopismo kwartalne poświęcone historii i krytyce literatury polskiej (in Polish). 2 (2): 5–14. doi:10.18318/pl.2019.2.1. ISSN 0031-0514.

- ^ Rocznik Biblioteki Naukowej PAU i PAN w Krakowie (in Polish). Polska Akademia Umiejętności. 2010.

- ^ Zemanek, Bogdan (2021). "Michał Kleczkowski – kuzyna żywot paralelny". Studia Norwidiana (in Polish). 39 (39): 293–310. doi:10.18290/sn2139.15. ISSN 0860-0562. S2CID 244453655.

- ^ Norwid, Cyprian (1971). Pisma wszystkie: Listy (in Polish). Państwowy Instytut Wydawniczy.

- ^ "Norwid Cyprian, "Ad leones!" - Materiały dodatkowe – galeria wiedzy Wydawnictwa Naukowego PWN". encyklopedia.pwn.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 2023-03-25.

- ^ Samsel, Karol (2016). "On "taking the bones away": the body of Cyprian Norwid and Montmorency". Studia Norwidiana (34EV): 141–154. ISSN 0860-0562.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Norwid, Cyprian; Borchardt, Danuta (2011-11-22). "Translator's note". Poems. Steerforth Press. ISBN 978-1-935744-53-5.

- ^ a b Trojanowska, Tamara; Niżyńska, Joanna; Czapliński, Przemysław (2018-01-01). Being Poland: A New History of Polish Literature and Culture since 1918. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-1-4426-5018-3.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Milosz, Czeslaw (1983-10-24). The History of Polish Literature, Updated Edition. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-04477-7.

- ^ Norwid, Cyprian (1981). "Preface". Vade-Mecum : Gedichtzyklus (1866) : polnisch/deutsch. Rolf Fieguth. München: Fink. p. 11. ISBN 3-7705-1776-8. OCLC 8546813. Translated to Polish as in: Jauss, Hans Robert. "Przedmowa do pierwszego niemieckiego wydania Vade-mecum Cypriana Norwida. (Przełożył z języka niemieckiego Michał Kaczmarkowski)." Studia Norwidiana 3 (1986): 3-11.

- ^ a b Wilson, Joshua (30 May 2012). "Flames of Goodness". The New Republic. Retrieved 30 May 2012.

- ^ Wojtasińska, Dominika (2014). "Ciemny hieroglif, czyli o kolejnych próbach rozjaśniania Norwida". Studia Norwidiana (in Polish). 32 (32): 261–280. doi:10.18290/10.18290/sn.2019.37-16. ISSN 0860-0562. S2CID 214423265.

- ^ DICKINSON, SARA (1990). ""His Soul is Marching On": Norwid and the Story of John Brown". The Polish Review. 35 (3/4): 211–229. ISSN 0032-2970. JSTOR 25778512.

- ^ Sajdek, Wiesława (2016). "Motywy filozoficzne w poezji Cypriana Norwida". Roczniki Kulturoznawcze (in Polish). 7 (3): 59–80. doi:10.18290/rkult.2016.7.3-4. ISSN 2082-8578.

- ^ Lyszczyna, Jacek (2016). Cyprian Norwid. Poeta wieku dziewiętnastego (in Polish). Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Śląskiego. ISBN 978-83-8012-878-1.

- ^ Stanisz, Marek (2018). "On the scientific gift for Professor Stefan Sawicki, with general remarks on modern Norwid Studies". Studia Norwidiana. 36 English Version (36EV): 277–300. doi:10.18290/sn.2018.36-13en. ISSN 0860-0562.

- ^ Brzozowski, Jacek (2014). "Uwagi o tomach trzecim i czwartym Dzieł wszystkich Cypriana Norwida". Studia Norwidiana. 32: 233–260. doi:10.18290/10.18290/sn.2019.37-15. ISSN 0860-0562.

- ^ Trojanowiczowa, Zofia (1986). "Uwagi o pierwszych dwu tomach Pism wszystkich Cypriana Norwida w opracowaniu Juliusza W. Gomulickiego" (PDF). Studia Norwidiana 3. 3: 243–250.

- ^ "Norwid laid to rest in Wawel Cathedral". info-poland.icm.edu.pl. Retrieved 2023-03-08.

- ^ Konopka, Blanka (April 13, 2021). "Award-winning Quay brothers create Norwid film to promote poet's work to foreign audiences". The First News. Retrieved 14 April 2021.

- ^ Konopka, Blanka (September 24, 2021). "'Underappreciated' poet Norwid honoured on his 200th birthday with events across the country". The First News.

- ^ Van Cant, Katrin (2009). "Historical Memory in Post-Communist Poland: Warsaw's Monuments after 1989". Studies in Slavic Cultures. 8: 90–119.

- ^ Brogan, Terry V. F. (2021-04-13). The Princeton Handbook of Multicultural Poetries. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-22821-1.

- ^ Rygielska, Małgorzata (2012). Przyboś czyta Norwida (in Polish). Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Śląskiego. ISBN 978-83-226-2066-3.

- ^ Korpysz, Tomasz (2018). "Introducion". Colloquia Litteraria. 4.

- ^ DICKINSON, SARA (1991). "Review of Cyprian Norwid (1821-1883): Poet - Thinker - Craftsman (A Centennial Conference), Bolesław Mazur, George Gömöri". The Polish Review. 36 (3): 363–366. ISSN 0032-2970. JSTOR 25778583.

- ^ "ISSN 2544-4433 (Online) | Studia Norwidiana | The ISSN Portal". portal.issn.org. Retrieved 2023-04-28.

- ^ "Polish Literature in English Translations:19th Century". polishlit.org. Retrieved 2023-04-07.

- ^ "The Larva - Cyprian Kamil Norwid". www.mission.net. Retrieved 2023-03-19.

- ^ "Mother Tongue - Cyprian Kamil Norwid". www.mission.net. Retrieved 2023-03-19.

- ^ "MY SONG (II) - Cyprian Kamil Norwid". www.mission.net. Retrieved 2023-03-19.

- ^ "To Citizen Johna Brown". www.mission.net. Retrieved 2023-03-19.

- ^ "What Did You Do to Athens, Socrates? - Cyprian Kamil Norwid". www.mission.net. Retrieved 2023-03-19.

- ^ "Cyprian Kamil Norwid, In Verona :: Wolne Lektury". wolnelektury.pl. Retrieved 2023-03-19.

- ^ "Fortepian Szopena - Wikiźródła, wolna biblioteka". pl.wikisource.org (in Polish). Retrieved 2023-03-19.

- ^ "Daily Observer | 24 February 2015, tuesday". www.eobserverbd.com. Retrieved 2023-03-08.

- ^ Dąbrowicz, Elżbieta (2021-09-30). ""Poezje" Cypriana Norwida z 1863 roku jako świadectwo autorecepcji". Pamiętnik Literacki (in Polish). 2021 (3): 107–120. doi:10.18318/pl.2021.3.6. ISSN 0031-0514. S2CID 245224098.

External links[edit]

- Speech made by Pope John Paul II to the representatives of the Institute of Polish National Patrimony

- Biography links

- Norwid laid to rest in Wawel Cathedral

- Repository of translated poems

- Cyprian Kamil Norwid collected works (Polish)

- Profile of Cyprian Norwid at Culture.pl

- Works by or about Cyprian Norwid at Internet Archive

- Works by Cyprian Norwid at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Why You Should Read Norwid, Poland's Starving Time Traveller from Culture.pl

- 1821 births

- 1883 deaths

- People from Wyszków County

- 19th-century Polish painters

- 19th-century Polish male artists

- Polish sculptors

- Polish male sculptors

- Polish male dramatists and playwrights

- Polish Roman Catholics

- Roman Catholic writers

- Activists of the Great Emigration

- 19th-century sculptors

- 19th-century Polish poets

- 19th-century Polish dramatists and playwrights

- Polish male poets

- 19th-century Polish male writers

- 19th-century Polish philosophers

- Polish male painters