A sample text widget

Etiam pulvinar consectetur dolor sed malesuada. Ut convallis

euismod dolor nec pretium. Nunc ut tristique massa.

Nam sodales mi vitae dolor ullamcorper et vulputate enim accumsan.

Morbi orci magna, tincidunt vitae molestie nec, molestie at mi. Nulla nulla lorem,

suscipit in posuere in, interdum non magna.

|

Hershel Parker also deals with the twelve poems that constitute the Live Oak, with Moss sequence. He identifies the time they originated – ‘within two years or so’ of the publication of 1856 edition of Leaves of Grass. In early 1859, according Parker, Whitman copied these twelve poems in a notebook under the title Live Oak, with Moss (the title is, unlike in Helms’s article, written with comma). The poems never got published as the sequence, and Parker too, notes that Whitman shuffled, dispersed and revised the poems and included them in the 1860 edition of Leaves. In this article, Parker, just like Helms in his article, states Fredson Bowers as the person who was the first to realize that twelve, seemingly random poems from the Calamus cluster are really the sequence telling the story of a homosexual affair. However, Parker provides more information about the publication of these findings – Bowers published these in 1953 in the Studies in Bibliograph and in Whitman’s Manuscript:’Leaves of Grass’(1860): A Parallel Text in 1955.

Parker, then, brings up the fact that from 1953/55 until 1994 when he published the sequence in the Norton Anthology of American Literature and called it ‘what today would be termed “gay manifesto”’, the sequence was generally neglected. In addition to this, Parker provides some of the probable reasons for such a neglect of this literary and culturally important material.

Firstly, he states that Studies in Bibliography is ‘highly specialized scholarly journal’ which makes it a kind of elitist journal, with not so wide readership. Also, this implies that, since it is so specialized journal it was not available to many colleges and many teachers/students. However, apart from this unavailability of the material, Parker suggests that the subject matter of the poems, such as it is, might have been a factor which contributed to the neglecting of the Live Oak, with Moss. This especially applied to the teachers, since the homoeroticism is not something generally perceived as ‘classroom safe’ topic. Finally, he offers the possibility that critics and scholars remained silent for so long about these poems because they were never published in their original form, so they were treated as if ‘they never had a tangible existence’.

The second part of Parker’s essay is dedicated to criticism of Alan Helms’s article Whitman’s Live Oak with Moss. He sees Helms’s article was ‘the first full attempt to read the Live Oak, with Moss’. Still, he finds many of Helms’s beliefs and many of the facts he presented erroneous and attacks Helms fiercely. Firstly, he finds it is close to sacrilege that Helms chose to provide the 1860 versions of the poems in question while talking about the Live Oak, with Moss (he even thinks that writing the title without comma is a great flaw and at several instances, calls Helms’s article the ‘no-comma Live Oak’). The Live Oak, with Moss poems printed in 1860 edition of the Leaves , according to Parker, are revised and are not identical to the original poems of the sequence and thus cannot be analyzed as the Live Oak poems, but rather as the Calamus poems. In other words, he does not so much question Helms’s interpretation, as much as he is trying to point out that it is not the interpretation resulting from the analysis of the ‘real’ Live Oak poems but revised, Calamus poems. At one point he goes so far as to bring up the possibility that Helms might not have even read the original sequence.

To emphasize this view of his, Parker then moves on to analyze every poem and, as awful as it sounds, point to mistakes Helms made because he used ‘wrong’ versions. Consequently, he does not accept ‘homophobic oppression’ as a pervading theme of the sequence but thinks that what these poems really show ‘Whitman’s accepting of his homosexuality and surviving a thwarted love affair’.

Parker’s conclusion is, then, that the two completely different reading of the Live Oak, with Moss (or Live Oak with Mos) are the result of reading two different sets of poems. In the end, he even claims that Helms’s reading is somehow didactically wrong? because it would discourage any gay or lesbian trying to come out.

All in all, Hershel Parker’s article introduces a completely different reading of these twelve poems and provides his arguments for his reading which is all in all important because it helps us understand that the existence of different interpretations of poems is possible. Even more so in the case of Whitman who revised his poems from edition to edition which made it possible for new interpretations to emerge, as a result of these revisions. Parker also emphasized one crucial thing in the process of reading Whitman’s poems and that is the choice of material. He came to one conclusion reading one version of the sequence, while Helms came to different conclusion reading another version of the same sequence of poems. Meaning, then, in case of Walt Whitman is not stable; it is fluid and susceptible to change and that is a good thing, because it means that there is still some place left for new and fresh interpretations.

In his article, Whitman’s Live Oak with Moss, Alan Helms discusses a sequence of twelve poems Whitman wrote ‘short time’ before 1859, when he copied them in a notebook under the title Live Oak with Moss. The sequence was first discovered, as Helms says, ‘almost forty years ago’ by Fredson Bowers who published it in Studies in Bibliography, and later in Whitman’s Manuscripts: Leaves of Grass (1860). The Live Oak with Moss sequence tells the story about love affair with a man, and in Helms opinion, testifies of the painful process of coming out. Helms goes even further to identify the lover in the poems as Fred Vaughan, a young man who lived with Whitman in late 1850s, but fails to produce any kind of evidence to support his speculation.

Since Bowers ‘findings’ were published the sequence was mainly neglected by both, scholars and teachers and Helms believes that this was mostly done due to the subject matter of the poems, that is homosexual affair. Also, the fact that these poems as a sequence were never published by Whitman himself, led Helms into introducing the theme of ‘homophobic oppression’ as the main theme of the entire sequence. That Whitman later shuffled and dispersed the poems from the Live Oak with Moss among the poems of the Calamus cluster, and published them all together in the 1860 edition of Leaves of Grass served as a proof to support his idea that Whitman was aware of cultural taboos and that he was, in a way ashamed of himself. Author further claims that Whitman’s awareness of the dangers lurking those like him in that homophobic society, even managed to silence him in a way, since he never published the sequence on its own, nor did he ever returned to the topic after the third edition of the Leaves.

Good portion of Helms’s article was devoted to the analysis of the actual poems of this sequence which he identified as poems from the Calamus cluster in the following order: 14, 20, 11, 23, 8, 32, 10, 9, 34, 43, 36 and 42 and which he provided at the end of his article in the mentioned order. Then he identified a kind of key words, in his opinion, of the entire sequence: confusion, pain and fear. He continued with the analysis of every poem, mostly in terms of ‘transgression – retreat’ revealing Whitman as an oppressed victim, ashamed and silenced.

However, in addition to the content, Helms addresses Whitman’s style in Live Oak with Moss poems. Since the poems are written in a kind of sonnet form, that Helms compares to Shakespear, he sees it as a kind of of compensation; the more Whitman transgressed the more he turned to ‘conventionally approved forms’ and that had a negative impact on Whitman’s style. Moreover, this deterioration of style, Helms disucsses, could be the result of the subject matter (homosexual love), and the difficulties Whitman might have experienced trying to come up with an appropriate vocabulary. According to Helms, the existing vocabulary did not allow Whitman to express himself without feeling shame.

The article end in the repeated idea of ‘homosexual oppression’ and the bleak and gloomy atmosphere of the Live Oak with Moss sequence is re-established.

Now, even though Helms’s critique of the sequence in question has its downsides, there are some aspects of it that can be very useful for us. Even though I am not so receptive of such a negative undercurrent in these poems, the confusion and fear and pain are, without any doubt, present in some of the poems and in our analyses it will serve us well to be aware of the inner conflicts of the author and consequent pain he feels. Also, the fact that Whitman obviously had his share of doubts about the publication of the Live Oak with Moss sequence leaves us a lot of room for new, bold (why not) interpretations concerning the state of the I in these poems. Still, the thing I believe will probably be the most helpful is Helms’s idea about (in)appropriacy of the language that was available to Whitman for the images and experiences he wanted to describe. In other words, if we consider not only what is said, but also what is not said and what was made ambiguous for some reasons, new, fresh interpretations just might start pouring out.

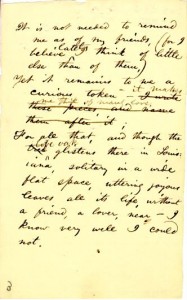

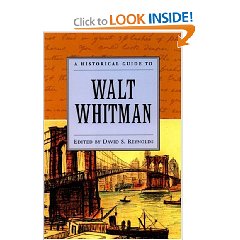

A Historical Guide to Walt Whitman

edited by David S. Reynolds (click on the image to go to the Amazon.com shop)

This book is part of a series “Historical Guides to American Authors” and starts with an introduction by the editor David S. Reynolds. He also contributes with a short biography of the poet.

This is followed by scholarly essays by well knows Whitmaniacs including Ed Folsom, which an average Whitman lover definitely did come across. In his essay he deals with Whitman’s stance on racism. Moreover, he specifically pinpoints places in Whitman’s poetry where he mentions or uses a metaphor to refer to black people. He focuses on poems “The Sleepers” and “Ethiopia Saluting the Colors” in his essay.

In the next essay, Jerome Loving writes about the Leaves as political poems which is definitely interesting to read because people not so often discuss these poems as political. Whitman was a great democrat and a patriot, and for someone who wants to deal with these topics, this is a must read. I would advise this part to be read together with the last essay “Whitman the Democrat” because both deal with similar but in many ways different notions. Politics and human rights are closely linked. One of the basic human rights is a right to express love. Killingsworth’s essay “Whitman and the Gay American Ethos” , as the title says looks at Whitman as a gay poet. The author finds examples of this in I Sing the Body Electric, Calamus clusters.

Roberta Tarbell speaks of links between the visual arts and Whitman. A large portion of the essay deals with architecture and technological advances in architecture which I did not find very interesting. On the other side of the medallion, the parts of the essays describing Whitman and love of photography and painting were really insightful. Worth a look. Tarbell finishes with Whitman’s influence on the coming artists.

One of the most useful thins I found in this book is definitely the illustrated chronology of Whitman’s life and career.

O DROPS of me! trickle, slow drops,

| Candid, from me falling—drip, bleeding drops, |

From wounds made to free you whence you were

prisoned,

|

| From my face—from my forehead and lips, |

From my breast—from within where I was con-

cealed—Press forth, red drops—confession

drops,

|

Stain every page—stain every song I sing, every

word I say, bloody drops,

|

| Let them know your scarlet heat—let them glisten, |

| Saturate them with yourself, all ashamed and wet, |

Glow upon all I have written or shall write, bleed-

ing drops,

|

| Let it all be seen in your light, blushing drops.

In this poem, all Whitman’s pain comes to the surface. It flows like a stream, it is not hidden anymore.

What caught my attention is Whitman’s “scarlet heat” that is put onto pages of his 1860 edition of “Leaves of Grass”.

Whitman’s confession is red, bloody. Like Nathaniel Hawthorne’ s Hester Prynne, who wore the scarlet letter “A”,

a badge of shame, Whitman wore his scarlet letter inside of him.

His conception of being different is transformed into words and put on the paper. He says “confession drops, stain every

page”. One of the meanings of the word “stain” given in Oxford dictionary is “to damage the opinion that people

have of something”. Connotation of this word here is negative. The poet admits something in this poem that is wrong

for public opinion. This confession is painful but finally, his supressed thoughts and feelings are liberated.

Also, interesting fact is that the covers of this edition are red. Whitman’s premonition of the American Civil War made

him design the covers in the colour of blood.

|

This documentary consists of an Introduction, nine shorter parts (approx. 7-13 minutes long) sorted chronologically and a Credits section. The nine sections follow Whitman’s life from his early days in New York, through his difficulties with publishing Leaves of Grass and his Civil War experiences, all the way to his last editing attempts in the “Death-Bed Edition” of Leaves.

Personally, I liked the Slavery and the Coming Crisis section best. Whitman’s life in New Orleans and the influenc

es there are very well portrayed in this part of the documentary. I very much agree with Ed Folsom saying: “He sees slave auctions take place. And as he sees bodies of human beings for sale he is stunned by the brutality and the sheer physical force of the experience.” Although we did mention this in class, I was captured by the phrase sheer physical force which seems so Whitmanian. I could see myself there, alongside Whitman, being stunned by the awful practices

that were carried out. The archival images during this part of the documentary were really vivid and they contributed to this realistic feeling.

This documentary could be really useful not just for my project but for all of our final projects. It is well divided in thematic sections which deal with specific topic in Whitman’s career as a poet and his life. Since I haven’t been reading into literary critiques of the scholars, novelist, biographers and writers that contributed to this documentary, I am not entirely sure if there were many new ideas or thoughts expressed. Nonetheless, this could be a great resource for a multimedia project if any of the students decide to go in that direction.

NOT HEAVING FROM MY RIBB’D BREAST ONLY.

| NOT heaving from my ribb’d breast only, |

| Not in sighs at night in rage dissatisfied with myself, |

| Not in those long-drawn, ill-supprest sighs, |

| Not in many an oath and promise broken, |

| Not in my wilful and savage soul’s volition, |

| Not in the subtle nourishment of the air, |

| Not in this beating and pounding at my temples and wrists, |

Not in the curious systole and diastole within which will one day

cease,

|

| Not in many a hungry wish told to the skies only, |

Not in cries, laughter, defiances, thrown from me when alone far

in the wilds,

|

| Not in husky pantings through clinch’d teeth, |

Not in sounded and resounded words, chattering words, echoes,

dead words,

|

| Not in the murmurs of my dreams while I sleep, |

| Nor the other murmurs of these incredible dreams of every day, |

Nor in the limbs and senses of my body that take you and dismiss

you continually—not there,

|

| Not in any or all of them O adhesiveness! O pulse of my life! |

Need I that you exist and show yourself any more than in these

songs. |

This poem first grabbed my attention with Whitman’s use of Not at the beginning of each line, and ending the poem with a line that starts with the powerful word Need. While reading it (and re-reading it numerous times) I stumbled upon a word which we mentioned several times in our class session. Adhesiveness is referred in this poem as the pulse of the poets life. Being that he did not know how to give name to his feelings he borrowed a word from phrenology denoting same-sex friendships.

I went to the Merriam-Webster’s Online dictionary and found the term adhesiveness which, of course, has to do more with adhesive tape than with same-sex love.

This is a very powerful poem in which Whitman shows his dissatisfaction with the American non-tolerant society and his difficulty to express his new-found way of loving people.

P.S. I am not quite sure why there isn’t a copy of the manuscript page of this poem in the Barrett Manuscripts. If anyone manages to find one, be sure to “link me”. Thanks.

The documentary „The American Experience: Walt Whitman“ by Mark Zwonitzer

A documentary very stimulating and suggestive, with capacity to illuminate all the central problems in Walt Whitman’s life, skillfully combining autobiographical, sociological, historical and religious themes. A story told in a lively and engaging way inviting numerous impressions, conclusions and above all feelings about Whitman and his work but also about ourselves and our lives in the modern society. Just as Martin Espada says at one point that „I see his Brooklyn. And strangely enough, I think he saw my Brooklyn“, throughout the documentary one feels very close to the world and life of Walt Whitman and very often while Whitman is speaking of his time we feel he is actually speaking of our time. Is not that „urban affection“ something that concerns us also- us brushing against strangers in the streets, forcing our way through the crowd, preoccupied with everyday worries and enormous to-do lists, not noticing the myriad of faces disappearing in front of us as fast and mechanically as a underground passes by leaving no trace behind? Is not that particular feeling of alienation, awareness of isolation woven into us, making us emotionally paralysed and numb? However, the documentary successfully displays Whitman as overly sensitive finding his inspiration in „the daily human drama of the city streets“. That is something that dazzles, his opening of a window to the smells, sounds and impressions of a „simple life“, his ability to see beauty in the „heavy, dense, uninterrupted street-bass“. The documentary brings one nearer to Whitman the poet and Whitman the man, communicating in a appealing and understandable way the idea that Whitman is trying to speak for everybody and to everybody, as he writes in the opening lines of Leaves of Grass:

„ I am the poet of the body and I am the poet of the soul. I go with the slaves of the earth equally with the masters. And I will stand between the master and the slaves, entering into both so that both will understand me alike.“

A collage of various characters like scholars, writers, poets, historians and biographers combined with tremendously good choice of music, photography and voices (Chris Cooper did a wonderful job as a voice of Walt Whitman) contributes to stripping the documentary of any dull moments all along and captivating our attention in a sort of a little spasm of excitement what we will hear next.

This is a true glimpse into Whitman’s life and work, provoking us to think and consider all the difficulties, sufferings, aspirations, regrets but also joys and happiness of our lives now and then.

The documentary stresses out that Whitman left Leaves of Grass to anyone who would have it after his death, no wife or children to inherit such a treasure chest of human emotions and thoughts, rather to everybody, the same way he completed it, saying:

“If you want me again look for me under your boot soles…failing to fetch me at first keep encouraged. Missing me one place search another. I stop somewhere waiting for you.“

This is a significant and exposing „slice of life“ and no doubt you will enjoy it!

My dear colleagues,

I could not resist the temptation to draw your attention to the story about one of Karen’s students, a sophomore art major named Alice Wetterlund, that you may read on the page XLIV in the book Karen gave us. I was almost touched to tears while reading this passage, because I was confronted with such a tremendous source of energy and power of written word. I felt I was there with Alice, we became one, her voice my voice, carried over the hubbub of Henry Street. I felt her excitement rushed through my veins end exploded in such a wonderful moment of true happiness and bliss. I cast off all my fears and anxieties, social customs and expectations, flooded with a feeling of revelation. Alice did what Whitman hoped for; she raised her voice above the simplicity and restrains of our everyday lives but also above herself. She spoke for herself, for you and me, for everybody, just as Whitman did. I felt the spell of the poetry spilled all over the place.

“I saw the marriage of the trapper in the open air in the far-west . . . . the bride was a red girl, “I saw the marriage of the trapper in the open air in the far-west . . . . the bride was a red girl,

Her father and his friends sat nearby crosslegged and dumbly smoking . . . . they

had moccasins to their feet and large thick blankets hanging from their

shoulders;

On a bank lounged the trapper . . . . he was dressed mostly in skins . . . . his luxuriant

beard and curls protected his neck,

One hand rested on his rifle . . . . the other hand held firmly the wrist of the red girl,

She had long eyelashes . . . . her head was bare . . . . her coarse straight locks

descended upon her voluptuous limbs and reached to her feet.

The runaway slave came to my house and stopped outside,

I heard his motions crackling the twigs of the woodpile,

Through the swung half-door of the kitchen I saw him limpsey and weak,

And went where he sat on a log, and led him in and assured him,

And brought water and filled a tub for his sweated body and bruised feet,

And gave him a room that entered from my own, and gave him some coarse clean

clothes,

And remember perfectly well his revolving eyes and his awkwardness,

And remember putting plasters on the galls of his neck and ankles;

He staid with me a week before he was recuperated and passed north,

I had him sit next me at table . . . . my firelock leaned in the corner.”

Although there are many sections in the poem that are just breathtaking, I chose this passage from the 1855 version of “Leaves of Grass” as my favorite. Walt Whitman is, in my humble opinion, one of the few poets that succeeds in portraying the exact image to his readers. While reading this passage about the marriage of a trapper and a red girl and the story about the runaway slave, I was more than astonished by the scenes that seemed to happen right in front of me.

At the time when the poem was written there were many talks and debates concerning tolerance, slavery, equality etc. These two scenes show Whitman’s stance on the matter, and very well draw a pretty precise sketch of my opinion on these antebellum problems.

I was positively overwhelmed with the amount of work we did during our first class period on the 31st. The introductory class was great and the high point was definitely reading the poem out loud, and holding the old green “Leaves of Grass” copy. Can’t wait for Saturday!

A live oak

According to the Merriam-Webster’s dictionary, the live oak is any of several American evergreen oaks noted for its extremely hard tough durable wood. You could say that it’s a powerful symbol of strength and you wouldn’t be mistaken. But if I asked someone from Texas what live oak means to him, I would probably get an answer: “Beer!”

Since most people from Serbia are not acquainted to the finest beers of the North American continent, an average Serbian would just shrug his shoulders to the same question. What was interesting for me was the fact that it is not like any oak I have ever seen around here. Its massive structure is impressing, but what is even more interesting is the moss growing on the trees giving them a striking appearance.

(Ancient live oak trees in Georgia)

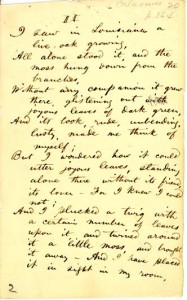

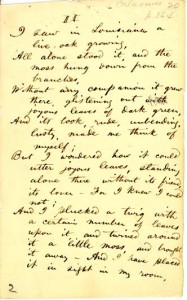

“I saw in Louisiana a live-oak growing,

All alone stood it and the moss hung down from the branches,

Without any companion it grew there uttering joyous leaves of dark green,

And its look, rude, unbending, lusty, made me think of myself,

But I wonder’d how it could utter joyous leaves standing alone there without its lover near—for I knew I could not.

And I broke off a twig with a certain number of leaves upon it, and twined around it a little moss,

And brought it away—and I have placed it in sight in my room,

It is not needed to remind me as of my own dear friends,

(For I believe lately I think of little else than of them,)

Yet it remains to me a curious token—it makes me think of manly love;

For all that, and though the live-oak glistens there in Louisiana solitary in a wide flat space,

Uttering joyous leaves all its life without a friend, a lover near,

I know very well I could not.”

(Calamus, 1860)

Whitman speaks of a tree that is alone, solitary, isolated in Louisiana without a lover near. There lies a different, more homoerotic aspect behind the lines, besides mere solitude. He mentions that the oak reminds him of manly love, of a person who is waiting for his lover and even the branches look rude and lusty to him. Indicative enough…

|

|

“I saw the marriage of the trapper in the open air in the far-west . . . . the bride was a red girl,

“I saw the marriage of the trapper in the open air in the far-west . . . . the bride was a red girl,