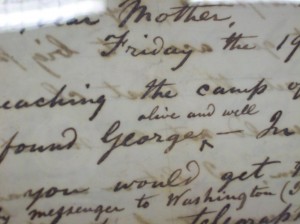

I am indebted to Other Sam for drawing my attention to this very moving detail. One of the best things I saw at the Library of Congress was Whitman’s letter of December 29, 1862 (that is, exactly 106 years before the day I was born), to his mother about finding George in Fredericksburg. We were able to read aloud his words about the suffering of the soldiers putting other suffering into perspective. We have read this letter in a collected of selected letters: “Dear, dear Mother, . . . I succeeded in reaching the 51st New York, and found George alive and well–in order to make sure that you would get the good news, I sent back by messenger to Washington (I dare say you did not get it for some time), a telegraphic dispatch . . .” What is not visible in that version of the letter is the revision Whitman made, no doubt anticipating the anxiety with which his mother would scan the letter if she had not received the “telegraphic dispatch” or was desperate for information about her wounded son. Lovely:

WWsites

Free tickets to Ford’s Theater for 19 people through Ticketmaster plus $2.00 access fee? $49.50. Thirteen hours of parking for three vehicles? $30.00. Bodily presence? Priceless.

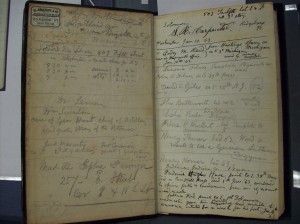

Immediacy is something the Reverend talks about as a benefit of the blog, social networking technologies, and the great digital experiment that is Looking for Whitman. Presence. Accessibility. These are words we use a lot. So this week a question has been dogging me while I process Digital Whitman’s Saturday field trip to Washington City. This pair of images sets it up:

WW notebook #94, Library of Congress American Memory site

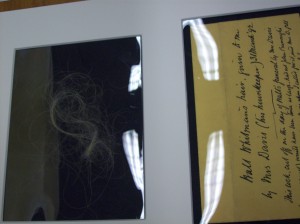

The one on top is from a link to the Library of Congress I gave the class a few weeks ago, urging them to use these digitized images to study what OMW recorded about the soldiers. The bottom was taken on our field trip, and is surprisingly focused given that I, Brady Earnhart, and our students were nearly all literally in tears in that weird institutional room with lockers, blackened windows, and government-issue tables. Unless we were crying with simple gratitude for the incredible time that Barbara Bair had given us (or because we were soaked to the bloody skin and had been standing for 10 hours with two or three to go), why were we? Nothing was much easier to read in person, as those of us who stumbled reading aloud can attest (writing still spidery, bleeding through paper, plastic protection on many items reflected flourescent glare, etc.). We couldn’t touch anything (though, good lord, we certainly breathed all over it), couldn’t feel the paper, the wood, the leather, the hair (the hair!).

I couldn’t even smell the leather of that haversack or of its decay, and I have one good super-sniffer.

Obviously, what I am suggesting is this: the artifacts of the Library of Congress archive were in some ways no more accessible or immediate (indeed, let’s be honest, a lot LESS accessible or even immediate if we mean time instead of proximity) than the digitized images of those artifacts online. I saw that the inside of the haversack is brown canvas. Brendon found a fingerprint and will NOT entertain suggestions that it belongs to anyone but Walt Whitman. But tears?

Presence. Through the blog we are present to each other online even when we are physically apart during the week (or have never seen each other: hallooo out there, Brooklyn, Camden, and Novi Sad!). Agreed. But finally Saturday we were (good) old-fashioned groupies, we were Whitman lovers, and we were bodies (finer than prayer, but, geez, we were a bit rank by Hour Ten of the marathon). We desired the physical–the textured, the pasted, the water-stained. We may have cried because the broken skins of brittle pages and fragile covers, the light-sensitive [associative digression: Whitman's Camden eyeglasses: so small, and with one lens protectively glazed over after strokes] and subsequently entombed haversack, and the tickets to a lecture on Lincoln long since delivered were as close to Whitman (brittle, entombed…) as we are going to get, as present as we can be. Unlike the wounded soldiers, we won’t get the healing presence of his 200-pound, hirsute, maroon-coated, deep-pocketed self. But it turns out that the digitized can’t hold a gas lamp to the physically present, and even if it’s paper and not flesh, I’ll take it. Whitmaniacs, pass the tissues.

Free tickets to Ford’s Theater for 19 people through Ticketmaster plus $2.00 access fee? $49.50. Thirteen hours of parking for three vehicles? $30.00. Bodily presence? Priceless.

Immediacy is something the Reverend talks about as a benefit of the blog, social networking technologies, and the great digital experiment that is Looking for Whitman. Presence. Accessibility. These are words we use a lot. So this week a question has been dogging me while I process Digital Whitman’s Saturday field trip to Washington City. This pair of images sets it up:

WW notebook #94, Library of Congress American Memory site

The one on top is from a link to the Library of Congress I gave the class a few weeks ago, urging them to use these digitized images to study what OMW recorded about the soldiers. The bottom was taken on our field trip, and is surprisingly focused given that I, Brady Earnhart, and our students were nearly all literally in tears in that weird institutional room with lockers, blackened windows, and government-issue tables. Unless we were crying with simple gratitude for the incredible time that Barbara Bair had given us (or because we were soaked to the bloody skin and had been standing for 10 hours with two or three to go), why were we? Nothing was much easier to read in person, as those of us who stumbled reading aloud can attest (writing still spidery, bleeding through paper, plastic protection on many items reflected flourescent glare, etc.). We couldn’t touch anything (though, good lord, we certainly breathed all over it), couldn’t feel the paper, the wood, the leather, the hair (the hair!).

I couldn’t even smell the leather of that haversack or of its decay, and I have one good super-sniffer.

Obviously, what I am suggesting is this: the artifacts of the Library of Congress archive were in some ways no more accessible or immediate (indeed, let’s be honest, a lot LESS accessible or even immediate if we mean time instead of proximity) than the digitized images of those artifacts online. I saw that the inside of the haversack is brown canvas. Brendon found a fingerprint and will NOT entertain suggestions that it belongs to anyone but Walt Whitman. But tears?

Presence. Through the blog we are present to each other online even when we are physically apart during the week (or have never seen each other: hallooo out there, Brooklyn, Camden, and Novi Sad!). Agreed. But finally Saturday we were (good) old-fashioned groupies, we were Whitman lovers, and we were bodies (finer than prayer, but, geez, we were a bit rank by Hour Ten of the marathon). We desired the physical–the textured, the pasted, the water-stained. We may have cried because the broken skins of brittle pages and fragile covers, the light-sensitive [associative digression: Whitman’s Camden eyeglasses: so small, and with one lens protectively glazed over after strokes] and subsequently entombed haversack, and the tickets to a lecture on Lincoln long since delivered were as close to Whitman (brittle, entombed…) as we are going to get, as present as we can be. Unlike the wounded soldiers, we won’t get the healing presence of his 200-pound, hirsute, maroon-coated, deep-pocketed self. But it turns out that the digitized can’t hold a gas lamp to the physically present, and even if it’s paper and not flesh, I’ll take it. Whitmaniacs, pass the tissues.

Free tickets to Ford’s Theater for 19 people through Ticketmaster plus $2.00 access fee? $49.50. Thirteen hours of parking for three vehicles? $30.00. Bodily presence? Priceless.

Immediacy is something the Reverend talks about as a benefit of the blog, social networking technologies, and the great digital experiment that is Looking for Whitman. Presence. Accessibility. These are words we use a lot. So this week a question has been dogging me while I process Digital Whitman’s Saturday field trip to Washington City. This pair of images sets it up:

WW notebook #94, Library of Congress American Memory site

The one on top is from a link to the Library of Congress I gave the class a few weeks ago, urging them to use these digitized images to study what OMW recorded about the soldiers. The bottom was taken on our field trip, and is surprisingly focused given that I, Brady Earnhart, and our students were nearly all literally in tears in that weird institutional room with lockers, blackened windows, and government-issue tables. Unless we were crying with simple gratitude for the incredible time that Barbara Bair had given us (or because we were soaked to the bloody skin and had been standing for 10 hours with two or three to go), why were we? Nothing was much easier to read in person, as those of us who stumbled reading aloud can attest (writing still spidery, bleeding through paper, plastic protection on many items reflected flourescent glare, etc.). We couldn’t touch anything (though, good lord, we certainly breathed all over it), couldn’t feel the paper, the wood, the leather, the hair (the hair!).

I couldn’t even smell the leather of that haversack or of its decay, and I have one good super-sniffer.

Obviously, what I am suggesting is this: the artifacts of the Library of Congress archive were in some ways no more accessible or immediate (indeed, let’s be honest, a lot LESS accessible or even immediate if we mean time instead of proximity) than the digitized images of those artifacts online. I saw that the inside of the haversack is brown canvas. Brendon found a fingerprint and will NOT entertain suggestions that it belongs to anyone but Walt Whitman. But tears?

Presence. Through the blog we are present to each other online even when we are physically apart during the week (or have never seen each other: hallooo out there, Brooklyn, Camden, and Novi Sad!). Agreed. But finally Saturday we were (good) old-fashioned groupies, we were Whitman lovers, and we were bodies (finer than prayer, but, geez, we were a bit rank by Hour Ten of the marathon). We desired the physical–the textured, the pasted, the water-stained. We may have cried because the broken skins of brittle pages and fragile covers, the light-sensitive [associative digression: Whitman's Camden eyeglasses: so small, and with one lens protectively glazed over after strokes] and subsequently entombed haversack, and the tickets to a lecture on Lincoln long since delivered were as close to Whitman (brittle, entombed…) as we are going to get, as present as we can be. Unlike the wounded soldiers, we won’t get the healing presence of his 200-pound, hirsute, maroon-coated, deep-pocketed self. But it turns out that the digitized can’t hold a gas lamp to the physically present, and even if it’s paper and not flesh, I’ll take it. Whitmaniacs, pass the tissues.

Free tickets to Ford’s Theater for 19 people through Ticketmaster plus $2.00 access fee? $49.50. Thirteen hours of parking for three vehicles? $30.00. Bodily presence? Priceless.

Immediacy is something the Reverend talks about as a benefit of the blog, social networking technologies, and the great digital experiment that is Looking for Whitman. Presence. Accessibility. These are words we use a lot. So this week a question has been dogging me while I process Digital Whitman’s Saturday field trip to Washington City. This pair of images sets it up:

WW notebook #94, Library of Congress American Memory site

The one on top is from a link to the Library of Congress I gave the class a few weeks ago, urging them to use these digitized images to study what OMW recorded about the soldiers. The bottom was taken on our field trip, and is surprisingly focused given that I, Brady Earnhart, and our students were nearly all literally in tears in that weird institutional room with lockers, blackened windows, and government-issue tables. Unless we were crying with simple gratitude for the incredible time that Barbara Bair had given us (or because we were soaked to the bloody skin and had been standing for 10 hours with two or three to go), why were we? Nothing was much easier to read in person, as those of us who stumbled reading aloud can attest (writing still spidery, bleeding through paper, plastic protection on many items reflected flourescent glare, etc.). We couldn’t touch anything (though, good lord, we certainly breathed all over it), couldn’t feel the paper, the wood, the leather, the hair (the hair!).

I couldn’t even smell the leather of that haversack or of its decay, and I have one good super-sniffer.

Obviously, what I am suggesting is this: the artifacts of the Library of Congress archive were in some ways no more accessible or immediate (indeed, let’s be honest, a lot LESS accessible or even immediate if we mean time instead of proximity) than the digitized images of those artifacts online. I saw that the inside of the haversack is brown canvas. Brendon found a fingerprint and will NOT entertain suggestions that it belongs to anyone but Walt Whitman. But tears?

Presence. Through the blog we are present to each other online even when we are physically apart during the week (or have never seen each other: hallooo out there, Brooklyn, Camden, and Novi Sad!). Agreed. But finally Saturday we were (good) old-fashioned groupies, we were Whitman lovers, and we were bodies (finer than prayer, but, geez, we were a bit rank by Hour Ten of the marathon). We desired the physical–the textured, the pasted, the water-stained. We may have cried because the broken skins of brittle pages and fragile covers, the light-sensitive [associative digression: Whitman’s Camden eyeglasses: so small, and with one lens protectively glazed over after strokes] and subsequently entombed haversack, and the tickets to a lecture on Lincoln long since delivered were as close to Whitman (brittle, entombed…) as we are going to get, as present as we can be. Unlike the wounded soldiers, we won’t get the healing presence of his 200-pound, hirsute, maroon-coated, deep-pocketed self. But it turns out that the digitized can’t hold a gas lamp to the physically present, and even if it’s paper and not flesh, I’ll take it. Whitmaniacs, pass the tissues.

Free tickets to Ford’s Theater for 19 people through Ticketmaster plus $2.00 access fee? $49.50. Thirteen hours of parking for three vehicles? $30.00. Bodily presence? Priceless.

Immediacy is something the Reverend talks about as a benefit of the blog, social networking technologies, and the great digital experiment that is Looking for Whitman. Presence. Accessibility. These are words we use a lot. So this week a question has been dogging me while I process Digital Whitman’s Saturday field trip to Washington City. This pair of images sets it up:

WW notebook #94, Library of Congress American Memory site

The one on top is from a link to the Library of Congress I gave the class a few weeks ago, urging them to use these digitized images to study what OMW recorded about the soldiers. The bottom was taken on our field trip, and is surprisingly focused given that I, Brady Earnhart, and our students were nearly all literally in tears in that weird institutional room with lockers, blackened windows, and government-issue tables. Unless we were crying with simple gratitude for the incredible time that Barbara Bair had given us (or because we were soaked to the bloody skin and had been standing for 10 hours with two or three to go), why were we? Nothing was much easier to read in person, as those of us who stumbled reading aloud can attest (writing still spidery, bleeding through paper, plastic protection on many items reflected flourescent glare, etc.). We couldn’t touch anything (though, good lord, we certainly breathed all over it), couldn’t feel the paper, the wood, the leather, the hair (the hair!).

I couldn’t even smell the leather of that haversack or of its decay, and I have one good super-sniffer.

Obviously, what I am suggesting is this: the artifacts of the Library of Congress archive were in some ways no more accessible or immediate (indeed, let’s be honest, a lot LESS accessible or even immediate if we mean time instead of proximity) than the digitized images of those artifacts online. I saw that the inside of the haversack is brown canvas. Brendon found a fingerprint and will NOT entertain suggestions that it belongs to anyone but Walt Whitman. But tears?

Presence. Through the blog we are present to each other online even when we are physically apart during the week (or have never seen each other: hallooo out there, Brooklyn, Camden, and Novi Sad!). Agreed. But finally Saturday we were (good) old-fashioned groupies, we were Whitman lovers, and we were bodies (finer than prayer, but, geez, we were a bit rank by Hour Ten of the marathon). We desired the physical–the textured, the pasted, the water-stained. We may have cried because the broken skins of brittle pages and fragile covers, the light-sensitive [associative digression: Whitman's Camden eyeglasses: so small, and with one lens protectively glazed over after strokes] and subsequently entombed haversack, and the tickets to a lecture on Lincoln long since delivered were as close to Whitman (brittle, entombed…) as we are going to get, as present as we can be. Unlike the wounded soldiers, we won’t get the healing presence of his 200-pound, hirsute, maroon-coated, deep-pocketed self. But it turns out that the digitized can’t hold a gas lamp to the physically present, and even if it’s paper and not flesh, I’ll take it. Whitmaniacs, pass the tissues.

Free tickets to Ford’s Theater for 19 people through Ticketmaster plus $2.00 access fee? $49.50. Thirteen hours of parking for three vehicles? $30.00. Bodily presence? Priceless.

Immediacy is something the Reverend talks about as a benefit of the blog, social networking technologies, and the great digital experiment that is Looking for Whitman. Presence. Accessibility. These are words we use a lot. So this week a question has been dogging me while I process Digital Whitman’s Saturday field trip to Washington City. This pair of images sets it up:

WW notebook #94, Library of Congress American Memory site

The one on top is from a link to the Library of Congress I gave the class a few weeks ago, urging them to use these digitized images to study what OMW recorded about the soldiers. The bottom was taken on our field trip, and is surprisingly focused given that I, Brady Earnhart, and our students were nearly all literally in tears in that weird institutional room with lockers, blackened windows, and government-issue tables. Unless we were crying with simple gratitude for the incredible time that Barbara Bair had given us (or because we were soaked to the bloody skin and had been standing for 10 hours with two or three to go), why were we? Nothing was much easier to read in person, as those of us who stumbled reading aloud can attest (writing still spidery, bleeding through paper, plastic protection on many items reflected flourescent glare, etc.). We couldn’t touch anything (though, good lord, we certainly breathed all over it), couldn’t feel the paper, the wood, the leather, the hair (the hair!).

I couldn’t even smell the leather of that haversack or of its decay, and I have one good super-sniffer.

Obviously, what I am suggesting is this: the artifacts of the Library of Congress archive were in some ways no more accessible or immediate (indeed, let’s be honest, a lot LESS accessible or even immediate if we mean time instead of proximity) than the digitized images of those artifacts online. I saw that the inside of the haversack is brown canvas. Brendon found a fingerprint and will NOT entertain suggestions that it belongs to anyone but Walt Whitman. But tears?

Presence. Through the blog we are present to each other online even when we are physically apart during the week (or have never seen each other: hallooo out there, Brooklyn, Camden, and Novi Sad!). Agreed. But finally Saturday we were (good) old-fashioned groupies, we were Whitman lovers, and we were bodies (finer than prayer, but, geez, we were a bit rank by Hour Ten of the marathon). We desired the physical–the textured, the pasted, the water-stained. We may have cried because the broken skins of brittle pages and fragile covers, the light-sensitive [associative digression: Whitman's Camden eyeglasses: so small, and with one lens protectively glazed over after strokes] and subsequently entombed haversack, and the tickets to a lecture on Lincoln long since delivered were as close to Whitman (brittle, entombed…) as we are going to get, as present as we can be. Unlike the wounded soldiers, we won’t get the healing presence of his 200-pound, hirsute, maroon-coated, deep-pocketed self. But it turns out that the digitized can’t hold a gas lamp to the physically present, and even if it’s paper and not flesh, I’ll take it. Whitmaniacs, pass the tissues.

Saturday, October 24, Washington City: Some Info

Whitmaniacs,

A few notes for Saturday (check for updates!):

1. Carpool rendez-vous: Jefferson Circle behind Combs at 9:00 a.m.

2. Parking in DC: 1201 F St. NW, 20005

- Take 95 North to 395 North (follow signs from 95 for 395/495/Washington/Tysons)

- On 395, take 12th Street exit toward L’Enfant Promenade

- 12th Street (follow slight left at 11th St SW/12th street tunnel)

- Left onto Connecticut NW

- First right onto 14th St NW

- Right at F St NW

- Garage on your left

- If full, proceed straight to next garage, 1155 F Street NW

3. Meeting place for 11:00 a.m. walking tour (1.5-2 hours): Lafayette Square, Andrew Jackson Statue (adjacent to White House, H street NW/16th St NW)

4. Tour ends in Chinatown (H and I streets between 7th and 8th)– lunch on your own

5. Meaningful afternoon activities:

- Ford’s Theater (free tix required–Scanlon): 511 10th St NW, 20004-1402

- Smithsonian Museum of American History, 19th-century and Lincoln exhibits: on National Mall, 14th and Constitution NW

- your choice

6. Library of Congress– meet out front at 5:15 p.m.

- Madison Building, 101 Independence Ave SE, 20540 (corner of Independence and 1st SE), behind Capitol Bldg. complex

- 1.5-2 miles from Ford’s/Mall if you go by foot (can follow Independence along edge of Mall)

7. Back to cars and Fredericksburg

Under My Bootsoles Everywhere

I was reading in yesterday’s Washington Post in a piece called “Beyond ‘Great,’ to Exemplary” that Whitman’s “O Captain!” is one of about five works identified by the National Standards Initiative as it tries to give guidance to high school teachers about what students should know– with Austen, Morrison, and a few others, it was given as an exemplar of something requiring complex interpretive skills, and the article implied that the choice was probably not controversial. This got me thinking about a conversation I had with Professor Nina Mikhalevsky, whose Banned and Dangerous Art course I linked to some weeks ago. She was remarking to me that she can’t believe that Whitman, whom she characterized as a radical thinker, had become such a national icon. At the time, I was focused on Whitman’s desire to be recognized as a poet for/of his nation, which makes iconic status more sensible, but lately I’ve been musing more about. . .

Whitman, American Rebel Idol.

A few examples:

Walt Whitman High, Bethesda, MD

Walt Whitman High School, Huntington Station, NY

The Walt Whitman Bridge (PA-NJ)

The Walt Whitman Mall (Huntington Station, NY)

Walt Wit Beer (Philly)

LOC image, Whitman cigar box from 1898

Whitman-Walker AIDS clinic, Washington DC

Walt Whitman Hotel, Camden , NJ

Walt Whitman T from LOLA (one of many)

Walt Whitman Fence Company (NY)

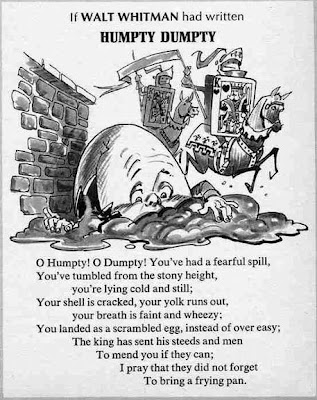

Mad Magazine, 1967

Campers at Camp Walt Whitman, Piermont, NH

Jesse Merandy (CUNY) with WW impersonator (Camden)

What?

Walt Whitman Golf (Bethesda)

WW Park (Brooklyn)

Obvious College Football connection

Seeing the United States Civil War Style

Here is a clear, color-coded map from wikimedia commons that shows the US as Whitman knew it: seceeding states, Union states with slavery, Union states without slavery, territories. And here is one that shows the same, but in a more traditional cartography: