Here is the link to my website, which contains all of my data and analysis. http://describing.lookingforwhitman.org/

I also have the spread sheet with all the answers; I think the map is up but just in case: Whitman Spread

Here is the link to my website, which contains all of my data and analysis. http://describing.lookingforwhitman.org/

I also have the spread sheet with all the answers; I think the map is up but just in case: Whitman Spread

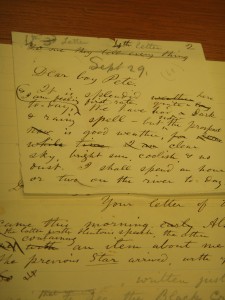

On our field trip to Washington DC, as we doggedly trekked back to the cars, Chelsea and I fell into conversation about Whitman’s letters. Of course, we were thrilled to have seen them and nearly touched them. The preciseness of Whitman’s handwriting and the possibility that one of the letters might have had his fingerprint was incredible. What was even more incredible about the letters, I think, was the fact that they were physical evidence of Whitman’s transcendence of time. Not only had his words and thoughts survived, but they were still able to touch a group of college students and turn them into weepy messes. Even something as simple as his revisions brought on tears, and then his letters…Oh, Walt. I know I’ve said this before, but the “I will get well yet” will always stick with me.

It got both Chelsea and I thinking: in the age of technology, with emails and AIM, what is our legacy going to be like? Emails and IMs are deleted within minutes and what with their ability to be instantaneous, I think we tend to make them a lot more impersonal. There’s just something lacking when you type in Times New Roman, size 12. Furthermore, where are they going to be saved? How are we going to pass some of these things on for people a hundred years ahead?

Granted, I think part of the reason we are able to take Whitman’s letters to heart today is because he knew he was going to be pretty special. Score one for egotism But I can’t help wonder what his legacy would be like if Whitman was reduced to 140 characters (sorry, Jim Groom!). At any rate, the idea has made me get out my pens and write some letters via snail mail. I even sealed them with wax. So maybe I’m not going to be famous like Whitman, and future generations would probably care less what I wrote to my grandmother, but at least my children might one day get a glimpse of what I and my super trippy handwriting were like (I’ve been told I have the cursive of a serial killer, seriously).

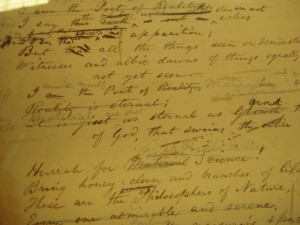

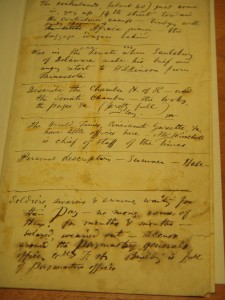

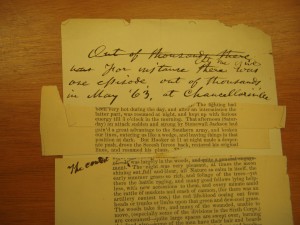

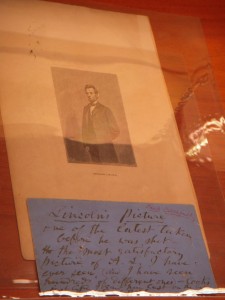

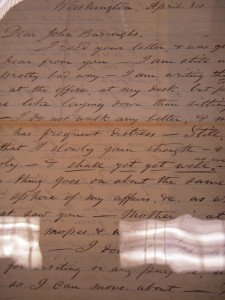

Okay. At the risk of this not having anything much to do with our field trip, I’m going to post several of the pictures of Whitman’s letters and handwritten notes. I dare you not to tear up a little (or at least the Whitmaniacs in Digital Whitman, anyway).

I found Whitman on Sandpiper Road, in Virginia Beach, VA. Because Whitman takes so much pride in being a “son of Manhatta,” it’s rather fitting that it was here, as this is where I (very proudly) hail from. Oh, PS: Excuse my crazy hair and the cameraman’s finger that apparently appears three-quarters of the way through. I never noticed it until I got back to Fredericksburg.

Oh, Walt.

We’re pretty much at the final stretch for this class, and having dealt with his death (where I was a very weepy individual), it seems appropriate that we now look at what Whitman has left us. Or, to be more specific, I suppose, what the world has done with Whitman now that we only have his poetry to guide us.

We claim Whitman as the American poet, but interestingly enough, I don’t really know if he can take only that title. I think that Whitman has established World Status. Our readings alone stretch his influence across oceans, and that’s not even a small part of those who have taken Leaves and made it part of themselves. The poet of our Nation has created other poets of Nations; Guo Moruo, for instance, was heavily influenced by the few translations he managed to get and has become one of the more influential poets in China. Moruo often responds to the idea of democracy and a revolution against traditionalism (much like Whitman’s rejection of classicism).

Take a look at a couple of these stanzas from the prefatory poem in Moruo’s The Goddesses:

I am a proletarian

Because except for my naked self, I possess nothing else.

The Goddesses is my own creation,

And may be said to be my private property,

Yet I want to be a communist,

Therefore I make her public to all.

Goddesses!

Go and find the one with the same vibrations as me,

Go and find the one with as may kindling points as myself.

Go and strike the heartstrings

In the breasts of the dear young brothers and sister,

And kindle the light of their wisdom!

Thematically, I can see Leaves resonating here. Moruo’s individualism stands out, with stark images such as “my naked self,” and the numerous uses of a possessive pronoun and “I.” The pride of his individualism is also present in the second stanza; although I’m still working out what “same vibrations” is, Whitman could easily have written these same words about himself, proclaiming the divinity of his poesy prophecy. Yet Moruo also rebels against individualism, his sense of unity is displayed in his desires to “make (Goddesses) public to all” and by placing both “brothers and sisters” in the same line, neither above the other. This line also makes Moruo a teacher in the sense that Whitman is; both seek to teach their political stances and ideals through poetry, uniting men and women through education.

Structurally, the two are similar as well; note the exclamation marks and the repetition of “Go,” which I think serves to reinforce the poet’s many points and the length of the journey one might have to go to find someone such as the poet. The fact that the last line never quite ends may imply that such a quest is also never ending. Because Moruo and others embraced Whitman so completely, Whitman has become one of the influential Western poets and one of the most studied. This is not to say that the Chinese completely look away from traditionalism; Whitman is also one of the most controversial Western poets because of his radical Western ideals.

I think that Whitman’s world influence is something that he would have been proud of. I mean, look at this stanza from “Salut Au Monde!”:

Within me latitude widens, longitude lengthens,

Asia, Africa, Europe, are to the east—America is provided for in

the west,

Banding the bulge of the earth winds the hot equator,

Curiously north and south turn the axis-ends,

Within me is the longest day, the sun wheels in slanting rings, it

does not set for months,

Stretch’d in due time within me the midnight sun just rises above

the horizon and sinks again,

Within me zones, seas, cataracts, forests, volcanoes, groups,

Malaysia, Polynesia, and the great West Indian islands.

Yes, Whitman was a proponent of manifest destiny, and these lines definitely speak to the that. But that imperialism also applies to his words and ideas; Whitman knows that he will stretch across the map and infect every nation. As for his canonical status, that’s something else I think he may have appreciated; it provides the chance for the ideas of Leaves to spread to even more individuals, educated or not. What’s important about it though, is that those who are studying it pay attention to those ideals and learn from them, rather than merely sucking in his words and ignoring their purpose. Whitman, I am glad you never went to high school with me.

Okay. While I was doing work on my project, I found this, and I think it definitely merits a look. Leaves Unbound attempts to showcase various selections in “Laves of Grass” involving interpretive dance, chamber choirs, and naked people. Lots of naked people. Apparently there is a lot of chanting of various lines in the text, “From I contain multitudes” to “I celebrate myself.”

I’m really curious what you guys think of it–or even what you think Whitman would have thought of it. It certainly incorporates the unification of body and soul. But do you think that embodying and displaying Whitman’s themes were the ultimate goal, or was it simply an excuse to put nudity in performance art? Either way, it looks kind of awesome.

This field trip is going to take more blogs than I’ll have time for, but here’s a shot at the first one. I’ve been a Virginian all my life, so Washington, DC has never been a big deal for me. I went on this field trip, however, with Whitman in mind, and it completely changed the way I viewed everything. The mall is nearly the same every time I visit: a big stretch of patchy grass covered with tourists. It’s muddy and it’s crowded, and unless you’re en route to one of the Smithsonians, not all that interesting. But there’s something decidedly different when you look at it as a place that Whitman would have traveled on, crowded with soldiers and refuse.

We also visited the Library of Congress,the grand finale and the culmination of everything we’d been looking at. I remember being tired, achy, and definitely grumpy as we tromped around its parameters. And then we filed into the room, and I noticed table upon table set out with Whitman paraphernalia-kind of like Thanksgiving for a Whitmaniac. We crowded around the tables, eagerly snapping pictures and taking in everything that was spread out. We’ve talked about Whitman for hours on end, but having the artifacts made me feel closer to Whitman than ever before. I was literally inches away from things he had touched and loved, things that Whitman had known future generations would want to see.

Maybe I’m feeling particularly emotional with us nearing the end, but the phrase “I shall yet get well” on this letter makes me tear up.

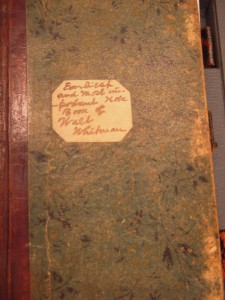

One of Whitman's hospital notebooks

Whitman's glasses. The right eye is frosted over.

Engraving on the Calamus Staff. Given to Whitman by Burroughs.

Whitman's hair. This seems to be a theme when Erin and I go on trips.

The.Haversack.

Oh, and by the way, most of us cried. When the haversack was unveiled, it felt like everything we had done in that class came together. It clicked on a level I’m not really sure I can describe (maybe this is the “discovering Whitman” episode we’ve been looking for?). Whatever it was, I felt more connected to Whitman and the rest of my class than I ever have before. It’s kind of incredible how something as simple as a letter or a bag can do that. Perhaps all it requires is a little touch of divine poesy.

I’ve been thinking a lot about the debates we’ve had in class concerning which edition of LoG was the better one. By the end of everything, however, the results were inconclusive: the few of us that preferred the 1855 edition were still set in our ways, as well as those who preferred the 1891-92 edition.

With that, I can’t help but think that there isn’t any definitive version to read, despite the fact that Whitman preferred his latest. The way our course is structured reflects this: we’ve dealt more critically with the “Drum-Taps” and Civil War editions than any other, while the other campuses take on their own edition reflecting their geography. And no campus really has a “better” edition or Whitman (although I will always be partial to my tender nurse Walt). Rather, each edition is definitive of the Whitman who was writing at the time as well as the country that he wished to save and unify, and each merits an equal amount of studying in order to best understand the changes and person in Whitman. If one wants to read a Whitman wounded from the war, then one should read the 1867 edition. The 1891-1892 is a matured Whitman, dealing with the effects of ill-health and the advent of a new century. Similarly, the other editions reflect other Whitmans, sober, youthful, or mournful.

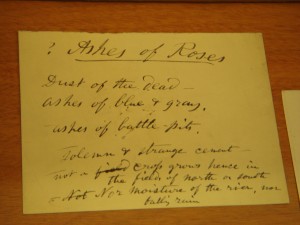

For example, I’ve been looking at “Ashes of Soldiers,” which appears in the “Songs of Parting” section of the deathbed edition. Until the 1867 edition this poem did not exist; it is a testament to the war and the losses that the nation suffered. 1855 is the triumphant youth of Whitman; the sobered sense of reflection wouldn’t make as much sense here. 1860 is the beginning of the tumult, and 1867 embodies a more sobered Whitman. In 1867, “Ashes” was known as “Hymn of Dead Soldiers,” a title that more closely defines the funereal and mournful outlook facing the nation post-war and post-Lincoln. The poem itself is also completely reworked. “Hymn” plunges into the physical aspects of the soldiers and war within the first several lines. “Ashes,” on the other hand, spends a good ten lines genuflecting on the ethereal aspects of the soldiers, as well as the idea that both North and South are dead. This transition is evident in the notes Whitman made here. Perhaps this is a reflection on Whitman’s older self, one who has had time to withdraw from the passions of war and is able to distance himself. Whitman even physically removes himself in “Ashes,” saying that he “muse(s) retrospective” and that the war “resumes.” The war is past tense and spiritual, rather than fresh and wounding. Rather than purely mourning the soldiers and being obsessed with their loss, Whitman also inserts the common theme of unification, reaffirming that the losses he felt were the losses of all the country. This also serves to reinforce mourning of the fractured nation.

Whitman’s sense of reflection is also evident in the latter parts of the text. Whitman adds the line, “Shroud them, embalm then, cover them all with tender pride.” Time plays an important role in “Ashes;” it literally enshrouds the memories here. While not necessarily softening them, it allows the speaker distance between himself and the war. Most of the changes take in this poem occur between 1867 and 1871. It’s only a span of four years, but the fact that Whitman allowed the poem to remain largely unedited until the deathbed edition may allow one to assume that Whitman’s general feelings on this aspect remain the same. The end lines are the only difference. Whitman places “South and North” to describe the soldiers, again reaffirming the theme of unification within the poem.

At the very beginning of this course, someone remarked that the 1855 edition of “Song of Myself” (or perhaps it was Leaves of Grass in general) was considered to be the superior text, and honestly, I think I have to agree. I know it’s more or less stating the obvious, but the speaker seems so much older than that of the 1891/1892 edition. Bear with me; I know that it’s kind of a “duh” statement.

In the 1891/92 edition, the poem has been section off-one dose of Whitman for every week in the year. The syntax, too, differs. Where the 1855 punctuation is spread out with a myriad of ellipses, this one contains rather domesticated looking commas (and every so often, a dash or two). The effect is similar to Whitman’s sectionalizing; it looks contained and sparse, almost as if Whitman deemed it necessary to have more organization in his life and work. But the 1855 seems more to hold true to his message; the sprawling text seems to emulate the author’s immense covering of the “Kosmos” and “multitudes.”

There are also several changes in diction that I found interesting-if not sometimes disconcerting. For instance, Whitman becomes “Walt Whitman, a kosmos, of Manhattan the son” (210). Where is the American? Why isn’t Walt one of the roughs anymore? It’s an interesting edit, particularly because I think it speaks so much to the message of “Song of Myself;” Whitman is defending himself as the all-American poet, the see-all, do-all, feel-all, be-all. Maybe that message changed somewhat, with the war. Whitman is an American, but perhaps he is more closely Manhattan than anything else, and being a Manhattan-ite is what validates him as American. I’m not really sure why “one of the roughs” is gone; it identifies so closely with the former image on the frontispiece. In the same vein, Whitman changes the line on 203; after one of his infamous lists, of these he “weaves the song of myself,” rather than “be[ing] more or less I am.” It’s almost as if Whitman is acknowledging that he can not be all of these people, can not do-all. But perhaps he can feel-all, and this he demonstrates with Song.

This entire section is stricken from section 18:

This is the breath of laws and songs and behaviour,

This is the the tasteless water of souls . . . . this is the true sustenance,

It is for the illiterate . . . . it is for the judges of the supreme court . . . . it is for the

federal capitol and the state capitols,

It is for the admirable communes of literary men and composers and singers and

lecturers and engineers and savans,

It is for the endless races of working people and farmers and seamen.

This is the trill of a thousand clear cornets and scream of the octave flute and strike

of triangles.

It disappeared from the 1867 edition and never returned. I imagine it’s because of the following section, wherein the speaker “play(s) marches for conquer’d and slain persons” (204). The earlier section detracts from the dead soldiers to whom Whitman became so close to. Within the text, the “victory marches” that Whitman mentions seem more for the capitols and seats of government and beings that caused the fractures that Whitman so desperately wanted to heal. And perhaps Whitman did not want his song characterized in the same vein as these individuals, particularly since “composers” and most “literary men” had no real idea what went on with the war; rather, they read the newspapers (some of which Whitman contributed to). Whitman’s evidence of the war is also shown later in this section; he “beat(s) and pound(s) for the dead” (205) rather than raise “triumphal drums” (44); it’s more of a dirge than a celebration here.

With experience, comes change-and Whitman certainly does that, revising his work as the nation continually revised itself. So, maybe I’m a little bit wrong. Perhaps it’s not so much that one edition is better than the other; perhaps it’s just that certain ones exemplify different aspects of his life-sometimes more efficiently than others.

Throughout our reading, Whitman has been a Lincoln-creeper (and I think that this was definitely solidified, when we saw the note yesterday that remarked how he had seen ‘hundreds’ of pictures of Lincoln). As I was reading this week, I tried to put Whitman not so much in the role of creepy Lincoln!fanboy, but rather as a Lincoln disciple. Although Whitman viewed himself as the poet-prophet, this was perhaps the one man who understood the unification of the nation that Whitman did. And where Whitman was the language, Lincoln was the enactor.

In “When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom’d,” there are several places that reminded me of this role. First of all, there is the Christ-like imagery. I don’t believe Erkilla. The lilac-star combination actually worked toward the Christ imagery in the piece. I looked into lilacs, and they’re considered an Easter flower, thus their sense of renewal tied with Lincoln automatically recalls Christ, particularly to an audience familiar with pastoral imagery. The star, too, is interesting. Perhaps it speaks to the legend that sprang up around the time of Lincoln’s funeral; during the procession in Washington, many mourners claimed that a bright star that had never been seen before appeared in the sky that day. To many of the mourners, this would have been seen as a sign from God—this was God calling Lincoln home.

In section 10, Whitman asks, “And what shall my perfume be for the grave of him I love,” which is reminiscent of John 12 in which the disciple, Mary, anoints Christ just before his death with costly perfume.

Throughout this poem, the speaker’s tone strikes me as particularly lost; he questions not only the best way to mourn for his fallen comrade, but what to do after his comrade has gone. The speaker mourns and clings to death, to the comrade. In this sense, it’s rather like a servant who has been left without a master, and who slowly learns to lean on himself.

Lincoln’s roles throughout “O Captain! My Captain!” may speak for themselves; although they speak to his leadership in the nation, they also speak to the personal leadership that Whitman sees in his goal of unification. This is one of the few times (if any other) we see Whitman defer the role of “Father” to another. Whitman takes the lower, servile role in this piece, attempting to revive his fallen loved one. Although we’ve seen a change in Whitman’s egotism in the war, his deference to praise is also remarkable; the speaker insists that the it is “for you the bugle trills” and the “bouquets and ribbon’d wreaths” and the “shores a-crowding” (476). There is no “I” here whatsoever; Whitman mentions that it is “our” journey—Lincoln and Whitman’s goal—but it is Lincoln who deserves the praise and the pedestal. It is as if Whitman bows out here, like an apprentice who has helped create but is displaying the master’s work as completely his own. That relationship dynamic alone is incredible, considering Whitman’s narcissism.

In “Collect,” Lincoln’s death is listed alongside that of Napoleon’s and Socrates. Each of these figures also had a similar disciple kind of following, particularly the latter (who, interestingly enough, also has a Christ-like martyrdom). Also interesting in “Collect” is Whitman’s unworthiness; his words “never offer” (1060). Rather than have Whitman create his portrait, Whitman maintains that four others must work together to do so (three great writers, Plutarch, Eschylus, and Rabelais, and a painter, Michel Angelo). It is as if Whitman is still stressing the servile, lower stance here; he is not quite good enough to convey everything about the master that he would like to.

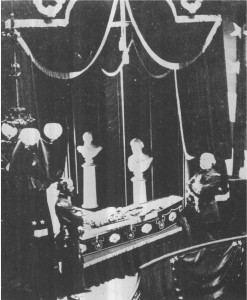

The funeral procession in Washington en route to the capitol.

Lincoln's Funeral Hearse in Washington. It was pulled by six white horses.

This is the only proven picture of Lincoln in death.

Lincoln was shot on April 15, 1865, at Ford’s Theater in Washington, DC (Kunhardt 119). Within hours of his death, Washington was scrambling to work on the preparations. The undertaker worked nearly nonstop 24 hours to produce Lincoln’s $1500 coffin, which measured 6 feet 6 inches long, a tight fit for Lincoln’s 6 feet 4 inches. Curiously, the coffin was decorated with four shamrocks on each side, with a star on the center of the broadest leaf. No one had ordered this. It has also never been explained, except that perhaps the undertaker’s artist was Irish, and was told to design something meaningful (120).

Before the funeral, Lincoln’s body rested on a catafalque (a raised platform used to support a casket) in East Room of the White House. The structure stood as high as eleven feet, was eleven feet long, and was decorated with draped black velvet and crape. Designed by Benjamin B. French, it mimicked the “Lodges of Sorrow,” which are the central component in Masonic funerals. The underside of the canopy was white fluted satin, which was intended to catch the little light in the room and reflect it on the corpse’s face. Lincoln’s catafalque soon came to be known as the “Temple of Death,” because it stood in the White House a full five weeks; Mary Todd Lincoln was so distraught that she begged officials not to take it down until she had moved out of the White House (120). Although small changes have been made to reinforce the structure, Lincoln’s catafalque is still used today for the funerals of presidents; it was most recently used for former President Ford’s (121).

The public in Washington was allowed to view the body that Tuesday. Lincoln’s official funeral was scheduled for Wednesday, April 19 (130). The city was packed; over a hundred thousand people had come to watch the procession and say goodbye to the president. Most arrived already in mourning, decorated with black crape tied to their arms, or pictures of Lincoln hanging over their hearts (123), and people were scrambling for places. Window seats cost as much as $100 (147). Wednesday began with the booming of cannons from all the forts surrounding the city, as well as bells tolling from the churches and fire departments. At exactly 12:10, Dr. Hall began the Episcopal burial service. Then, Bishop Simpson of the Methodist Episcopal Church spoke, and Dr. Gurley, Lincoln’s pastor, delivered the funeral sermon (Goodrich 188). While this was going on, all over the nation, and even in Canada, there were similar services being delivered for the president (Kunhardt 129).

The procession to the capitol soon followed the funeral. Once the coffin had been loaded on to the car, which was pulled by six white horses, the bells and cannons resumed. A detachment of black soldiers led; they had been the second troop to enter Richmond upon its surrender. Black citizens made the most impressive showing of grief out of all the mourners at the procession; nearly 4,000 walked in lines of forty straight across the road, holding hands and carrying signs. Just following the hearse was Lincoln’s favorite horse, which had been branded “U.S.” and was carrying his master’s boots backwards in the saddle (131). Once they reached the capitol, the body was then laid in the rotunda for several days, and the public was again allowed to view Lincoln.

Lincoln’s popularity and martyrdom caused an insurmountable amount of grief around the city. Lincoln was a legend, and just as when any legend dies, so do more legends and tales spring up. Some people claimed that the day of the funeral, a bright star had appeared in the sky over Washington. Another tale said that no wood thrush sang for an entire year after Lincoln’s death (132).

Mary Todd Lincoln never attended Lincoln’s funeral, or any of the following ones. She remained in bed nearly the entire time, claiming that she was too upset. When they moved the body to the catafalque, the bearers even removed their shoes because they were afraid that she would hear their footsteps and begin screaming(Goodrich 185). Mary Todd Lincoln also spoke to spiritualists claiming to have messages from her dead husband, which did not help her erratic nature. Nevertheless, these were the few people she would allow to see her. Eventually, Robert Lincoln put a firm stop to it in hopes that it would help soothe his mother (Kunhardt 249).

Although Lincoln’s official funeral was in Washington, DC, he was to have at least 12 more. His body was placed on a train on Friday, April 21st, so that it could travel part of the country and give citizens a chance to say goodbye . The body would end up in Springfield, where Lincoln would eventually be buried. Mary Todd Lincoln had also decided that their son, Willie, who had died three years earlier, would be exhumed and re-interred with his father (Goodrich 195). Both coffins were placed side by side in the second to last railway car and were joined by 300 passengers, containing officials, family members, and individuals integral to the cortege (Kunhardt 139).

The train’s trip was intended to include every city which the president-elect had stopped on his trip eastward to Washington in 1861: Baltimore, Harrisburg, Philadelphia, New York, Albany, Buffalo, Columbus, Indianapolis, Chicago, and finally, home to Springfield. The only exception to this was Cincinnati, which was ruled out because they deemed the southward trip too lengthy, much to the offense of the city (140).

The train was always greeted with enormous crowds and displays of mourning, almost as if each city was trying to outdo the others. One viewer disgustedly remarked that the great show made “their mourning…a fashion…[M]any come to such sights as they would to a wax work show” (Goodrich 232). Citizens often held signs that expressed such feelings as “Abraham Lincoln, the illustrious martyr of liberty, the nation mourns his loss, though dead, he still lives” (197). Before the public was allowed to view Lincoln, the undertaker had to quickly chalk the corpse’s face to hide discoloration, as well as literally dust him off. The constant opening and closing of the coffin, as well as the dirty state of most of its visitors often left Lincoln’s body nearly caked in grime (196).

Philadelphia’s funeral was one of the few marked by violence. When the train first arrived, an artillery piece exploded prematurely, injuring two people; this was an early indicator of the violence that was soon to come (197). Before the train had even arrived, mourners stood for miles even before the station; there were no gaps in the lines that stretched as far north as the Schuylkill River and as far east as the Delaware River (Kunhardt 150). When pickpockets began terrorizing a portion of the crowd (an act that was not uncommon during the funerals; gangs of pickpockets followed the train (Goodrich 236)), the line changed into a mob, and surged out far beyond the guiding ropes. Someone then cut the guiding ropes, which resulted in chaos. People began fighting. Many women fainted, and had to be passed out above the heads of the crowd (Kunhardt 150). Individuals also had their clothes ripped off of them, so that the streets were littered with torn petticoats and shirts (Goodrich 199). Police began sending people at the front of the mile-long line back to the end. By the end of the day, at least one woman had broken her arm, and two small boys were said to be dead, although they were later revived (Kunhardt 150). Because of the violence, police ensured a no-tolerance policy over the body; individuals were not allowed to stop and look at the body for even a second during the viewing, and many people had to be prevented from touching or even kissing Lincoln’s face (Goodrich 214).

The stop at New York was also marked with similar police action; they were said to bully the crowds and immediately escort out anyone who looked suspicious. The New York City Council ruled that colored citizens were not allowed to walk with the procession, much to the chagrin of the thousands of citizens that had come to see the president that had freed them (Kunhardt 153). However, the Secretary of War quickly sent a telegram to the city in response, begging that “no discrimination respecting color should be exercised in admitting person to the funeral procession” (154). 300 citizens marched, bearing a sign that said “Two million of bondsmen he liberty gave.” Their passing was the only time that applause broke out during the procession. Unfortunately, their dream of marching with the president did not entirely come true; the body was already out of New York and traveling up the Hudson by the time they walked(155).

When the body finally reached Illinois, the embalmers were having a lot of issues; onlookers often commented on how black the president’s face was becoming, as well as his shriveled appearance and pitted cheeks (Goodrich 242). One viewer likened him to a “mummy” (Kunhardt 240). Although he had finally gotten to his home state, Lincoln’s final resting place was still the source of much debate; Mary Todd wanted to choose the place that her husband would have wanted. Chicago was her first choice because it was where Lincoln had planned on settling after his presidency. Her second choice was the tomb built for Washington under the rotunda of the capitol (247). Finally, she decided on a cemetery outside of Springfield called “Oak Ridge,” because her husband wanted to be buried “in a quiet place” (248). Springfield citizens did not agree; they thought it was too far out of town. Instead, they purchased a stone house closer to the center of town, and began working that into a tomb. When Mary Todd Lincoln heard this, she was furious, and threatened to bury Lincoln in Chicago instead (242). The fight between the two parties grew so intense that Springfield citizens insisted Mary Lincoln had “no friends here” (249). Robert Lincoln put an end to the matter by quickly traveling to Springfield; Mary Lincoln again remained confined to her room. Finally, on May 4, 1965, nearly three weeks after Lincoln had been killed, he and his son were laid to rest . After 1700 miles (243), violence, celebration, and grief, Lincoln’s body had found its final home.

Works Cited

Goodrich, Thomas. The Darkest Dawn. Bloomington: University of Indiana Press, 2005. Print.

Gurney, Jeremiah Jr. “Lincoln in Death.”Photograph. Kunhardt, Dorothy Meserve and Philip B. Kunhardt Jr. Twenty Days. New York:Harper and Row Publishers, 1965, 162. Print.

Kunhardt, Dorothy Meserve and Philip B. Kunhardt Jr. Twenty Days. New York: Harper and Row Publishers, 1965. Print.

“Lincoln’s Funeral Train.”Photograph. Kunhardt, Dorothy Meserve and Philip B. Kunhardt Jr.Twenty Days. New York:Harper and Row Publishers, 1965, 147. Print.

“Washington During the Funeral.” Photograph. Kunhardt, Dorothy Meserve and Philip B. Kunhardt Jr. Twenty Days. New York:Harper and Row Publishers, 1965, 130. Print.