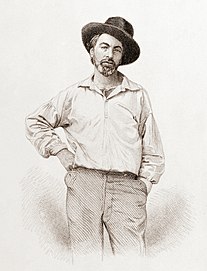

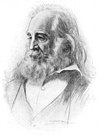

Walt Whitman's lectures on Abraham Lincoln

Walt Whitman gave a series of lectures on Abraham Lincoln from 1879 to 1890. They centered around the assassination of Abraham Lincoln, but also covered years leading up to and during the American Civil War and sometimes included readings of poems such as "O Captain! My Captain!". The lectures began as a benefit for Whitman and were generally popular and well received.

Whitman greatly admired Lincoln and was moved by his assassination in 1865 to write several poems in the president's memory. The idea of Whitman's giving lectures about the topic was first circulated by his friend John Burroughs in an 1878 letter. Whitman, who had long aspired to be a lecturer, gave his first lecture in New York City's Steck Hall on April 14 the following year. Over the course of the next eleven years, he gave the lecture at least ten more times, and possibly as many as twenty.

A delivery of the lecture in 1887 at Madison Square Theatre is considered to have been his most successful lecture. Described by Whitman's biographer Justin Kaplan in 1980 as the closest Whitman came to "social eminence on a large scale",[1] the lecture had many prominent members of American society in the audience. Whitman described the lecture as "the culminating hour" of his life,[1] but later criticized it as "too much the New York Jamboree".[2] He gave the lecture for the last time in Philadelphia in 1890, two years before his death.

Background[edit]

Walt Whitman established his reputation as a poet in the late 1850s to early 1860s after the 1855 release of Leaves of Grass.[3][4] The brief volume released in 1855 was considered controversial by some,[5] with critics particularly objecting to Whitman's blunt depictions of sexuality and the poem's "homoerotic overtones".[6] At the start of the American Civil War, Whitman moved from New York to Washington, D.C., where he held a series of government jobs—first with the Army Paymaster's Office and later with the Bureau of Indian Affairs.[7][8] He volunteered in the army hospitals as a nurse.[9]

Although they never met, Whitman saw Abraham Lincoln several times between 1861 and 1865, sometimes in close quarters. The first time was when Lincoln stopped in New York City in 1861 on his way to Washington.[10][11] He greatly admired the President, writing in October 1863, "I love the President personally."[12] Whitman later declared that "Lincoln gets almost nearer me than anybody else."[10][11] Lincoln's assassination on April 15, 1865, greatly moved Whitman and the nation. Shortly after Lincoln's death, hundreds of poems were written on the topic. The historian Stephen B. Oates noted that "never had the nation mourned so over a fallen leader".[13][11]

Whitman himself wrote four poems in tribute to the fallen President. "O Captain! My Captain!", "When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom'd", "Hush'd Be the Camps To-Day", and "This Dust Was Once the Man" were all written on Lincoln's death. While the poems do not specifically mention Lincoln, they turn the assassination of the President into a sort of martyrdom.[10][11] In 1875 Whitman published Memoranda During the War, which included a narrative of Lincoln's death.[14] The following year he published an article on Lincoln's death in The New York Sun,[15] and considered writing a book on Lincoln, but never did.[16]

Whitman and lectures[edit]

.jpg/220px-Ad_for_Whitman%27s_Lincoln_lecture_(1887).jpg)

In the mid-19th century, public lectures in the United States emerged as a place for prominent Americans to speak. As more high-profile people began lecturing, more Americans began attending lectures. Because of this, scholar David Haven Blake writes, the lecture became directly associated with celebrity and fame.[18] By the 1870s, Whitman had long sought to be a lecturer, writing several lectures and delivering at least one as early as the 1850s.[19]

In a letter written on February 3, 1878, Whitman's friend John Burroughs suggested that he deliver a lecture on Lincoln's assassination. Burroughs wrote that the poet Richard Watson Gilder also supported the idea and suggested delivery around the anniversary of the assassination, in April.[20][21][22] On February 24, Whitman responded to Burroughs, agreeing to the proposal. The next month, Whitman began experiencing severe pain in his shoulder and was partially paralyzed; as a result, the lecture was postponed to May. On April 18 the paralysis was attributed to a ruptured blood vessel in his brain by the physician Silas Weir Mitchell and in May he gave up on plans for the lecture that year.[23] In March 1879,[24] a group of Whitman's friends, including Gilder, Burroughs, and the jeweler John H. Johnston, again began planning a lecture.[24][16] As part of the preparations for the first lecture, Whitman worked his New York Sun article into a readable format.[20]

Deliveries[edit]

Between 1879 and 1890 Whitman delivered his lecture on the assassination of Lincoln a number of times.[25] Money made from these lectures constituted a major source of income for him in the last years of his life.[26]

The first lecture was given in Steck Hall, New York City, on April 14, 1879. Whitman was unable find further bookings for lectures for the rest of the year.[27] He did not give another lecture until April 15, 1880, in Association Hall, Philadelphia. He revised the lecture's content slightly for the second reading; it would stay in largely the same form for the remainder of his lectures.[28] Whitman gave the lecture again in 1881.[29] There are no records of him delivering it in the next five years, but he gave it at least four times in 1886, and several times in the ensuing four years.[25] Whitman's April 15, 1887 lecture at Madison Square Theatre is considered the most successful of the lectures, largely because it was attended by a number of notable figures.[30] He gave the lecture at least two further times, including his last delivery in Philadelphia on April 14, 1890, just two years before his death.[16][25] The text of the lecture was published in Whitman's Complete Prose Works.[31][32] Whitman also sent a written copy of the lecture to his friend Thomas Donaldson in 1886. Donaldson, in turn, sent the lecture to the author Bram Stoker, who received it in 1894.[33]

Whitman said that he gave the lecture a total of thirteen times,[34] but later scholars give varying numbers—estimates range as high as twenty.[a][14] Eleven individual deliveries have been identified:

| Date | Location | Description | Ref(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| April 14, 1879 | Steck Hall, New York City | To a group of 60 to 80 people, Whitman's first lecture on Lincoln. Whitman sat while delivering his lecture. The success of this lecture is unknown | [37][38][27] |

| April 15, 1880 | Association Hall, Philadelphia | The second known lecture, form modified slightly from the first. Whitman promoted this delivery, sending copies of the speech to several newspapers. | [28][39] |

| April 15, 1881 | Hawthorne Room of the St. Botolph Club, Boston | Over 100 attendees, including William Dean Howells. Raised $135, with tickets sold for $1 each. Organized by the Papyrus Club. Positively received by contemporary reviewers. After the Boston lecture, publisher James R. Osgood agreed to publish an edition of Leaves of Grass, which the historian David S. Reynolds attributes to the lecture and the associated increase in a perception of Whitman as a more conventional figure. | [40][29][41] |

| February 2, 1886 | Pythian Club, Elkton, Maryland | Given at the request of Whitman's friend Folger McKinsey as part of a public lecture series organized by the Pythian Journalists' Club . | [42] |

| March 1, 1886 | Morton Hall, Camden | [43] | |

| April 15, 1886 | Chestnut Opera House, Philadelphia | Attendees included Stuart Merrill and George William Childs. Arranged as a benefit for Whitman by actors and journalists and raised $692. | [44][45] |

| May 18, 1886 | Haddonfield, New Jersey | Delivered as a fundraiser to benefit a local Episcopal Church, the Collingswood Mission, that was constructing a new building. Local newspapers later described it as "a grand success" and reported that around $22 was raised. | [34] |

| April 5 or 6, 1887 | Unity Church, Camden. | Delivered to Camden's Unitarian Society. Described by Reynolds as "a modest affair". | [43][46][47] |

| April 14, 1887 | Madison Square Theatre, New York City | Generally considered the most successful lecture: though the theatre was not very full,[b] it was attended by notable societal figures including James Russell Lowell, Frances Hodgson Burnett, Edmund Clarence Stedman, Wilson Barrett, Mark Twain, Frank Stockton, Mariana Griswold Van Rensselaer, William T. Sherman, John Hay, José Martí, Stuart Merrill, and Augustus Saint-Gaudens. Reynolds described the lecture in 1995 as a "Barnumesque event on a high scale."[49] It was organized by Robert Pearsall Smith and several other friends of Whitman. At the end of the lecture, the poet Edmund Clarence Stedman's granddaughter brought Whitman lilacs and he read the "O Captain! My Captain!". A reception at Whitman's hotel suite after the lecture was attended by about two hundred people. Whitman later described the lecture and its aftermath as "the culminating hour" of his life;[1] he earned $600 from the event, of which $350 was from Andrew Carnegie, who may not have actually attended the lecture.[c] However, he also told his friend Horace Traubel that he considered the event "too much the New York Jamboree".[2] | [54][55][56][2] |

| April 14, 1889 | New York City | Attendees included John Hay. | [57] |

| April 14 or 15, 1890 | Philadelphia Art Gallery, Philadelphia | Given to the Contemporary Club. Whitman, undeterred by his failing health, spoke to a crowd of three to four hundred people.[d] He could reportedly only climb to the building's second floor with assistance and struggled to read his manuscript. A transcript was published in the Boston Evening Transcript of April 19. This was the last lecture; Whitman died two years later. | [60][61][62] |

Content[edit]

Whitman was described by scholar Merrill D. Peterson as not being an orator "either in manner or appearance".[16] Contemporary observers also described Whitman as a poor speaker,[27] saying that his voice would become higher than normal and describing it as "unnatural-sounding".[63] However, other sources describe him as speaking in a low voice.[16]

The lecture combined clippings of previously written material,[64] such as the article Whitman had published on Lincoln's death in the New York Sun,[20] Memoranda During the War, The Bride of Gettysburg by John Dunbar Hilton,[65] and some new content.[64] In preparing for the lecture, Whitman also considered the story of Demodocus, a divine bard portrayed in the Odyssey.[65]

According to scholar Leslie Elizabeth Eckel, Whitman generally began by "downplaying his ability to handle the emotionally challenging task that lay before him".[66] He then moved into describing the rise in tensions leading up to the 1860 presidential election[67] and America during the Civil War era. Then he would describe Lincoln's death, the main focus of the lecture.[66] Whitman described Ford's Theatre and the assassination in vivid detail, as if he had been there.[68][e] He identified the assassination as a force that would "condense—A nationality,"[66] equating Lincoln's killing to a sacrifice which would "cement [...] the whole people."[70]

Whitman brought a "reading book" with him to the lectures that contained fifteen poems he read at their conclusion.[71][f] He often read his poem "O Captain! My Captain!",[16] but the book contained five other poems from Leaves of Grass including "Proud Music of the Storm" and "To the Man-of-War-Bird". It also had clippings of the works of other poets such as "The Raven" by Edgar Allan Poe, poems by William Collins, and a translation of Anacreon's Ode XXXIII by Thomas Moore called "The Midnight Visitor".[25][72][71] Whitman revised the text of "The Midnight Visitor" that he delivered.[72]

Reception[edit]

The lectures were popular and well received.[16] Historian Daniel Mark Epstein wrote that Whitman's deliveries were always successful and usually attracted vast amounts of positive attention in local newspapers.[73] Scholar Michael C. Cohen called Whitman's lecture his "most popular text"[74] and Reynolds describes Whitman's lectures as making him a household name.[75] In 1988 professor Kerry C. Larson wrote that the "hackneyed" sentimentality of Whitman's lectures was indicative of a decline in his creativity.[76]

Because tickets were generally too expensive for the working class to attend,[77] the lectures were usually attended only by those who could afford tickets. According to Blake, these lectures allowed members of higher society to "pay homage to both the president and the poet". He emphasizes how Whitman used the lectures to connect America's love for Lincoln with his own poetry, namely Leaves of Grass.[78] Whitman's biographer Justin Kaplan wrote that Whitman's 1887 lecture in New York City and its aftermath marked the closest he came to "social eminence on a large scale",[1]

Many audience members reported being moved to tears.[25] José Martí, a Cuban journalist who was present at one of the lectures, wrote a laudatory account of the lecture that was spread across Latin America.[79] He described the crowd as listening "in religious silence, for its sudden grace notes, vibrant tones, hymnlike progress, and Olympian familiarity seemed at times the whispering of the stars." The poet Edmund Clarence Stedman wrote that "Something of Lincoln himself seemed to pass into this man who loved and studied him",[80] while the poet Stuart Merrill said that Whitman's telling of the assassination convinced him that "I was there, [that] the very thing happened to me. And this recital was as gripping as the messengers' reports in Aeschylus."[81]

Whitman also used the lectures to further perception of himself as a "public historian".[64] Promotional materials for the lecture often falsely claimed that Whitman had known well Lincoln and had been in Ford's Theatre upon the night of the assassination. An ad for his Elkton, Maryland, lecture in 1886 even said that Whitman had been in the room with Lincoln when he was shot.[17] English scholar Gregory Eiselein contrasted Whitman's depiction of Lincoln's death in his lectures with that in his poem "When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom'd." Whitman's lecture was intended to present a very factual account, in a tone that scholar Martin T. Buinicki has described as "pointedly historical". Conversely, "Lilacs" has a tone that Eiselein describes as "musical, ethereal, often abstract, [and] heavily symbolized."[64] Blake describes Whitman's lectures and the respect they received from high society as emphasizing a final "triumph" for Whitman, over the "slander and scorn" he had once experienced from the same group. He goes on to write that delivering the lecture regularly became "vital to his permanent achievement of [fame]."[82]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Barton wrote in 1965 that he considered thirteen to be "too large" and was able to compile a list of nine definite occasions.[35] Loving argued in 1999 that ten was "the best estimate".[36]

- ^ According to Kaplan 1980, p. 29, the theatre was a quarter filled. Loving 1999, p. 450 describes the auditorium as "sparsely crowded", while contemporary observer Stuart Merrill described a "thinly scattered" crowd. However, Johnston wrote that the theatre was packed.[48]

- ^ Sources conflict over whether Carnegie was in attendance at the lecture. Some, such as Whitman scholars Kaplan 1980, p. 29 and Krieg 1998, p. 154 and Carnegie biographer Nasaw 2007, p. 295, describe him as having been there, while others, including Pannapacker 2004, p. 55 and Blake 2006, p. 191, write that he did not come, despite having paid for his box. Loving 1999, p. 450 writes that Carnegie was not in the box that he paid for. Sources contemporary to the lecture are similarly conflicted; The New York Times lists Carnegie as having been in attendance,[50] while The Indianapolis Journal describes him as seated in the pit.[51] The New York Tribune wrote that Carnegie did not reach New York City until the evening of the 15th, at which point he remained in his room, too sick to see "even his most intimate friends",[52] and an article in The Critic wrote that Carnegie had been "unable to occupy" his box and paid Whitman the $350 when he reached New York "a day or two" after the lecture.[53]

- ^ While Reynolds describes the lecture as having been attended by a "cordial crowd of sixty to eighty",[58] Whitman's friend Horace Traubel, who was at the lecture, wrote that it was attended by "3 to 4 hundred" people.[59]

- ^ While Whitman had not seen Lincoln's assassination, he interviewed Peter Doyle, an intimate companion of Whitman, and based his lectures in part on Doyle's account.[69]

- ^ The original copy of the book is lost,[71] but its contents are described in Furness 1928, pp. 204–206.

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d Kaplan 1980, p. 31.

- ^ a b c Reynolds 1995, p. 555.

- ^ Miller 1962, p. 155.

- ^ Kaplan 1980, p. 187.

- ^ Loving 1999, p. 414.

- ^ "CENSORED: Wielding the Red Pen". University of Virginia Library Online Exhibits. Retrieved October 28, 2020.

- ^ Loving 1999, p. 283.

- ^ Callow 1992, p. 293.

- ^ Peck 2015, p. 64.

- ^ a b c Griffin, Martin (May 4, 2015). "How Whitman Remembered Lincoln". Opinionator. The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 12, 2020.

- ^ a b c d Eiselein, Gregory (1998). LeMaster, J. R.; Kummings, Donald D. (eds.). 'Lincoln, Abraham (1809–1865)' (Criticism). New York City: Garland Publishing. Retrieved October 12, 2020 – via The Walt Whitman Archive.

- ^ Loving 1999, p. 288.

- ^ Pannapacker 2004, p. 88.

- ^ a b Cushman 2014, p. 47.

- ^ Barton 1965, p. 191.

- ^ a b c d e f g Peterson 1995, pp. 138–139.

- ^ a b Blake 2006, pp. 188–190.

- ^ Blake 2006, pp. 35–37.

- ^ Barton 1965, pp. 187–188.

- ^ a b c Barton 1965, pp. 192–193.

- ^ Glicksberg 2016, p. 173.

- ^ Loving 1999, p. 386.

- ^ Krieg 1998, pp. 118–119.

- ^ a b Krieg 1998, p. 122.

- ^ a b c d e Griffin, Larry D. "Death of Abraham Lincoln (1879)". The Walt Whitman Archive. Retrieved January 8, 2021.

- ^ Reynolds 1995, p. 524.

- ^ a b c Allen 1967, p. 484.

- ^ a b Barton 1965, pp. 195–197.

- ^ a b Allen 1967, p. 491.

- ^ Barton 1965, p. 209.

- ^ Trimble 1905, p. 71.

- ^ Whitman 1892, p. 306.

- ^ Havlik 1987, pp. 9, 11.

- ^ a b Azarnoff, Roy S. (September 1, 1963). "Walt Whitman's Lecture on Lincoln in Haddonfield". Walt Whitman Review. IX: 65–66.

- ^ Barton 1965, pp. 194, 214.

- ^ Loving 1999, p. 440.

- ^ Barton 1965, pp. 192–194.

- ^ Reynolds 1995, p. 531.

- ^ Reynolds 1995, p. 534.

- ^ Krieg 1998, p. 132.

- ^ Reynolds 1995, pp. 531, 533–534.

- ^ Moyne, Ernest J. (December 1975). "Folger McKinsey and Walt Whitman". Walt Whitman Review. 21 (4): 135–144.

- ^ a b Barton 1965, p. 208.

- ^ Krieg 1998, p. 151.

- ^ Allen 1967, p. 524.

- ^ Krieg 1998, p. 154.

- ^ Reynolds 1995, p. 564.

- ^ Pannapacker 2004, p. 161.

- ^ Reynolds 1995, p. 554.

- ^ ""A Tribute from a Poet"". The New York Times. April 15, 1887.

- ^ "Walt Whitman Lectures on Lincoln". The Indianapolis Journal. April 15, 1887.

- ^ "Andrew Carnegie in Town". The New York Tribune. April 16, 1887. p. 4.

- ^ "Notes". The Critic. VII (173): 211. April 23, 1887.

- ^ "Walt Whitman Lectures on Abraham Lincoln". The Washington Post. April 15, 1887.

- ^ Epstein 2004, pp. 325–327.

- ^ Kaplan 1980, p. 30.

- ^ Barton 1965, p. 213.

- ^ Reynolds 1995, p. 575.

- ^ Traubel 1982, p. 365.

- ^ Blake 2006, p. 193.

- ^ Krieg 1998, p. 167.

- ^ Morris 2000, p. 242.

- ^ Marinacci 1970, p. 393.

- ^ a b c d Buinicki 2011, p. 145.

- ^ a b Bair, Barbara (April 14, 2021). "Remembrance: Whitman's "The Death of Lincoln" and the By the People Whitman Campaign | From the Catbird Seat: Poetry & Literature at the Library of Congress". From the Catbird Seat: Poetry and Literature at the Library of Congress. ISSN 2692-1723. Retrieved October 4, 2022.

- ^ a b c Levin & Whitley 2018, pp. 102–103.

- ^ Reynolds 1995, p. 441.

- ^ Blake 2006, p. 188.

- ^ Eiselein, Gregory. "Lincoln's Death". The Walt Whitman Archive. Retrieved January 8, 2021.

- ^ Blake 2006, p. 190.

- ^ a b c Grier 2007, p. 1054.

- ^ a b Golden, Arthur (October 1, 1988). "The Text of a Whitman Lincoln Lecture Reading: Anacreon's "The Midnight Visitor"". Walt Whitman Quarterly Review. 6 (2): 91–94. doi:10.13008/2153-3695.1208. ISSN 0737-0679.

- ^ Epstein 2004, p. 323.

- ^ Cohen 2015, p. 157.

- ^ Reynolds 1995, p. 496.

- ^ Larson 1988, p. 232.

- ^ Reynolds 1995, p. 536.

- ^ Blake 2006, pp. 190–193.

- ^ Allen 1967, p. 525.

- ^ Peterson 1995, pp. 139–140.

- ^ Levin & Whitley 2018, p. 102.

- ^ Blake 2006, pp. 193–194.

Bibliography[edit]

- Allen, Gay Wilson (1967). The Solitary Singer: A Critical Biography of Walt Whitman. New York City: New York University Press. OCLC 276385.

- Barton, William E. (1965) [1928]. Abraham Lincoln and Walt Whitman. Port Washington, New York: Kennikat Press. ISBN 9780804600187. OCLC 1145780794.

- Blake, David Haven (2006). Walt Whitman and the Culture of American Celebrity. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-11017-3.

- Buinicki, Martin T. (2011). Walt Whitman's Reconstruction: Poetry and Publishing Between Memory and History. Iowa City, iowa: University of Iowa Press. ISBN 978-1-60938-069-4.

- Callow, Philip (1992). From Noon to Starry Night: A Life of Walt Whitman. Chicago: Ivan R. Dee. ISBN 1566631335. OCLC 644050069.

- Cohen, Michael C. (2015). The Social Lives of Poems in Nineteenth-Century America. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-4708-4. JSTOR j.ctt15hvz5p.

- Cushman, Stephen (2014). Belligerent Muse: Five Northern Writers and How They Shaped Our Understanding of the Civil War. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: The University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-1-4696-1877-7. OCLC 875742493.

- Epstein, Daniel Mark (2004). Lincoln and Whitman: Parallel Lives in Civil War Washington (1st ed.). New York City: Ballantine Books. ISBN 0-345-45799-4. OCLC 52980509.

- Furness, Clifton Joseph (1928). Walt Whitman's Workshop: A Collection of Unpublished Manuscripts. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. OCLC 217561.

- Glicksberg, Charles I., ed. (2016) [1933]. Walt Whitman and the Civil War: A Collection of Original Articles and Manuscripts. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-1-5128-0167-5. JSTOR j.ctv51338s.

- Havlik, Robert J. (1987). "Walt Whitman and Bram Stoker: The Lincoln Connection". Walt Whitman Quarterly Review. 4 (4): 9–16. doi:10.13008/2153-3695.1148.

- Kaplan, Justin (1980). Walt Whitman, a Life. New York City: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 0-671-22542-1. OCLC 6305249.

- Krieg, Joann P. (1998). A Whitman Chronology. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press. ISBN 0-87745-654-2.

- Larson, Kerry C. (November 21, 1988). Whitman's Drama of Consensus. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-46908-9.

- Levin, Joanna; Whitley, Edward (May 31, 2018). Walt Whitman in Context. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-108-31447-3.

- Loving, Jerome (1999). Walt Whitman: The Song of Himself. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-21427-7. OCLC 39313629.

- Marinacci, Barbara (1970). O Wondrous Singer! An Introduction to Walt Whitman. New York City: Dodd, Mead & Company. OCLC 64241.

- Miller, James E. (1962). Walt Whitman. New York City: Twayne Publishers. OCLC 875382711.

- Morris, Roy, Jr. (2000). The Better Angel: Walt Whitman in the Civil War. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-512482-8. OCLC 43207497.

- Nasaw, David (2007). Andrew Carnegie. New York City: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-311244-0.

- Pannapacker, William (2004). Revised Lives: Whitman, Religion, and Constructions of Identity in Nineteenth-Century Anglo-American Culture. Milton Park, Abingdon: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-92451-5.

- Peck, Garrett (2015). Walt Whitman in Washington, D.C.: The Civil War and America's Great Poet. Charleston, South Carolina: The History Press. ISBN 9781626199736.

- Peterson, Merrill D. (1995). Lincoln in American Memory. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-802304-3.

- Reynolds, David S. (1995). Walt Whitman's America: A Cultural Biography (1st ed.). New York City: Knopf. ISBN 0-394-58023-0. OCLC 30547827.

- Traubel, Horace (1982). Traubel, Gertrude; White, William (eds.). With Walt Whitman in Camden: September 15, 1889-July 6, 1890. Vol. 6. Carbondale, Illinois: Southern Illinois University Press. OCLC 8856880.

- Trimble, W. H. (1905). Walt Whitman and Leaves of Grass: An Introduction. London: Watts & Company.

- Whitman, Walt (2007). Grier, Edward F. (ed.). Notebooks and Unpublished Prose Manuscripts: Camden. New York City: New York University Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-9437-1.

- Whitman, Walt (1892). Complete Prose Works. Philadelphia: David McKay.

_(cropped).png/330px-Walt_Whitman_on_Abraham_Lincoln_(1886_lecture_flyer)_(cropped).png)