Archive for category Uncategorized

Friends of Whitman

Posted by jackieg in Uncategorized, visitorscripts on December 11, 2009

How could you be a great mind like Walt Whitman and not have people be drawn to you? I’m sure it’s possible in some cases but Whitman not only had close friends who adored him, he had followers who based their course of life off of his words. That’s influence for you. Two such people were Edward Carpenter and Robert Ingersoll. These men, like many others, were so greatly affected by Whitman and in different ways. One was a devout follower of Whitman, more of a disciple, if you will. The other was a close friend and was actually an object of Whitman’s own admiration. Both of them were lucky enough to have a creative mind like Whitman’s in their lives.

Edward Carpenter was born in Hove, England and attended Brighton College. Although he would go on to Cambridge, Carpenter didn’t have a feeling for academics at a young age. Instead he discovered his attachment to nature and this relationship is one that lasted him the rest of his life. While attending University, Carpenter discovered his attraction to men and didn’t feel outwardly comfortable about his feelings right away.

Following his college years, and some time experimenting with men, Carpenter decided to become a Curate in the Anglican Church. Before long, he became unhappy with his life there. He seemed to find the Victorian era, in its entirety, a hypocrisy. His only way out of this fraudulent life he was living was through poetry. Carpenter received his first copy of Leaves of Grass in1868 and the rest is history.

Something in Whitman’s poetry moved him so much that Carpenter decided that he needed to educate the working class of the world. He picked up is life with the church and moved on to become a lecturer of astronomy and outspoken Socialist. After his father died and left him a considerable amount of money, he sought out a home in Milthrope and adapted a more natural lifestyle. This included, among other things, harvesting his own crops and vegetarianism. It was here in his life that he came to terms with his sexual orientation. Because of his new lifestyle away from the Victorian era, his creativity blossomed. One of his great works “Towards Democracy” was written during this time and was greatly influenced, as was the rest of his works, by Whitman.

Carpenter got the chance to visit Whitman in 1877 as well as in 1886 and chronicled these visits in his work, Days with Whitman. Carpenter wouldn’t have become who he was without Whitman giving him the strength to be radical and live how he wants to live. Whitman’s work was the driving factor in Carpenters decision to educate the lower class and that made all the difference in his life.

Whitman’s friend, Robert Ingersoll, was born in 1883 in Dresden, NY. He was the product of an intelligent, abolitionist family. He began studying law and during his time as a law clerk he opened his own practice with his brother, which they named “E.C. & R. G. Ingersoll”. When the Civil War broke out he took command of the 11th Illinois Cavalry Regiment. He was captured during this time and subsequently released on the grounds of giving his word to never fight again, which was common practice at the time. Following the war, Ingersoll became Attorney General of Illinois. His views were very radical for the time period and he was very outspoken. This did not help his political career, but helped his life as an orator greatly. He was incredibly affluent and his lectures ranged in many different genres, however he was very passionate about the ideas humanitarianism and free thought. Needless to say, his ideas appealed to Whitman. He considered Ingersoll to be the greatest orator of all time. Ingersoll was so admired by him that he was chosen to give the eulogy at his funeral, which must have been an incredible honor.

All three of these men shared a common bond; they all seem to be ahead of their time. Each one was filled with ideas that seemed radical for the late nineteenth century. Regardless of the time, they still put themselves out there in a way no one had done before. They paved the way for leaders to come. It’s obvious that great minds connect to one another, and these friendships and admirations illustrate that fact.

Adam L’s Visitor Center Script

Posted by adaml in Uncategorized, visitorscripts on December 10, 2009

Eugene V. Debs, a prominent socialist, union leader, and once presidential candidate for the American Socialist party (receiving his nomination in jail), acknowledged Whitman as an influence upon his political ideology. To illuminate Debs’ connection to Whitman, it is best to start with their mutual friend, Horace Traubel, who “is best known as the author of a nine-volume biography of Whitman’s final four years” (Folsom). He transcribed many conversations he had with Whitman, which often focused on politics and, specifically, socialism.

Traubel was born in Camden in 1858 to a father who was a printer by trade and a fan of Leaves of Grass. Traubel shared his father’s appreciation for Whitman’s poetry, and when the poet moved to Camden in 1873, the young man befriended him, and they developed a close friendship over the next twenty years. Throughout their friendship, Traubel “often tried to convince his mentor that America’s democratic promise could only be realized through socialism” (Garman 90). Whitman warned Traubel, however, that his socialism was too radical; the two never agreed politically, and although Whitman’s socialism “was a pliable as the poet himself,” Traubel contributed to perpetuating a much more radical posthumous socialist legacy for Whitman than the poet had supported in his lifetime. (Folsom). In 1890, Traubel founded a monthly called The Conservator, which was devoted to reporting Progressive reform organizations, and to keeping Whitman’s works alive. “In virtually every issue there would be essays on Whitman, reviews of books about Whitman, digests of comments relating to Whitman, advertisements for books by and about Whitman. Often, Whitman would be presented as a kind of proto-Ethical Culture thinker” (Folsom). Traubel often attempted to “connect his idol (Whitman) to Eugene V Debs’ Socialist party” in the publication (Garman 92). Accordingly, Debs often wrote for The Conservator, acknowledging Whitman as one of his primary influences (Bussell).

Born and raised in the Midwest, “his fight against capitalism was inspired as much by Tom Paine, Walt Whitman and Wendell Phillips as it was by Karl Marx” (Platt). Debs was imprisoned for his activism several times throughout his life, arrested for his involvement in the Pullman Strike, and later convicted of espionage and sentenced to 10 years in prison for speaking out against World War I (Robertson). He was later pardoned by President Harding, and died in a sanitarium.

Debs’ letters were later collected and published; his own words about Whitman’s influence upon his politics speak for themselves:

2-13-1908 EVD, Terre Haute, to Stephen [Reynolds]. I have been East. Agree with your letter about organizing; have an article about that in a recent Appeal. We have to do more than talk Socialism– must get our machine in shape for political action. Will get a list of Indiana workers for you from Comrade Wayland. Will try to carry out your suggestion that Appeal discuss organization weekly. Being in West Virginia reminded me of John Brown. You are doing an immortal service which Old Walt [Whitman] would applaud. TLS 2p E http://www.indianahistory.org/)

Works Cited

Bussel, Alan. “In Defense of Freedom: Horace L. Traubel and the Conservator.”

“Eugene V Debs Papers, 1881-1940.” Indianahistory.org. 2004.

http://www.indianahistory.org/library/manuscripts/collection_guides/SC0493.html#CATALOGING

Folsom, Ed. “With Whitman in Camden.” University of Iowa. 1996.

http://www.wlbentley.com/wwic/WWICfore.html

Platt, Pam. “Eugene V. Debs: The Hoosier Socialist. Courier Journal. November

Robertson, Michael. “The Gospel According to Horace: Horace Traubel And The

Walt Whitman Fellowship.” Mickel Street Review v 16. http://micklestreet.rutgers.edu/archives/Issue%2016/documents.htm

Michael G’s Visitor Center Script

Posted by jewbacca in Uncategorized, visitorscripts on December 10, 2009

Socialism: Whitman and Emma Goldman

Whitman’s influence has been surprisingly far-reaching. He was the model for Bram Stoker’s Dracula1, his lifestyle was adopted by the Beat movement including Allen Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac2, and many in the literary world consider him to be “America’s Poet” in the words of Ezra Pound3. However, his influence went beyond the world of literature and into the world of politics. Whitman’s egalitarian philosophy with respect to religion, sexuality, gender and race touched many a political activist, where equality for all is a commonality.

One such activist is the self-proclaimed atheist and anarchist Emma Goldman. Described during her life as “the most dangerous woman in America” by many4, she first came into contact with Whitman’s work while serving a year-long prison sentence for inciting a riot during a demonstration against unemployment in 18935. Among other American activist-writers such as Emerson and Thoreau, she read Whitman’s Leaves of Grass6. Other than this, however, she had absolutely no contact with Whitman. While they were contemporaries, Goldman was only in the United States for the last ten years of Whitman’s life.

She may have related to Whitman because of her similar views on certain issues. She shared the nearly unheard of view—even among anarchists—that homosexuals deserve the same rights as heterosexuals7, writing in numerous letters and speeches in the defense of gay rights. And, while Whitman was influenced by deism, he was skeptical of religious institutions and held no faith to be greater than any other; an atheist by declaration, I believe Goldman felt connected to Whitman’s sentiment regarding religion even as she vehemently denied the existence of G-d8.

But, that is essentially where the similarities end. While Whitman believed in a close relationship between poetry and society9, Goldman held a hypocritical view of activism in which violence that served her purposes was acceptable10 while even non-violent actions undertaken by those opposed to her were tyrannical and oppressive11. She helped conspire with her lover to murder the industrialist Henry Clay Frick, begging him to allow her to participate12; she also expressed approval of the ideals behind the assassination of President McKinley13. She organized strikes and demonstrations, often attempting to incite the participants to violence or disruptiveness14.

However, despite her wildly hypocritical views on appropriate tactics, she—like Whitman—had fairly far-reaching influence. Her work in women’s rights led to the creation of anarcha-feminism, which regards patriarchy as an establishment to be resisted. Goldman is often cited as the movement’s founder15. In the same light, her incessant championing of her ideals in the face of multiple arrests influenced the founder of the ACLU, Roger Baldwin16.

And so, while she did not have direct contact with Whitman, she may have felt that he was in league with her given his views on certain issues. Whitman has a way of conjuring his presence through the page, which Goldman may have sensed and used to bolster her belief that he would have supported her actions. Indeed, she included his poems in her self-published magazine, Mother Earth, and eventually wrote an essay on him in which she linked the deep meaning of his words to his homosexuality17. However, despite similar views on a limited number of topics, Whitman and Goldman could not be much more different in personality, tactics, and political views.

1Nuzum, Eric. The Dead Travel Fast: Stalking Vampires from Nosferatu to Count Chocula. Thomas Dunne Books, 2007: 141-147.

2Loving, Jerome. Walt Whitman: The Song of Himself. University of California Press, 1999: 181.

3Pound, Ezra. “Walt Whitman”, Whitman, Roy Harvey Pearce, ed. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, Inc., 1962: 8.

4Avrich, Paul. Anarchist Voices: An Oral History of Anarchism in America. AK Press, 2006: 45.

5Wexler, Alice. Emma Goldman: An Intimate Life. New York: Pantheon Books, 1984: 76.

6Ibid, 78-79.

7Katz, Jonathan. Gay American History: Lesbians and Gay Men in the U.S.A. New York: Penguin Books, 1992: 376-380.

8Goldman, Emma. “The Philosophy of Atheism”, Mother Earth. Self-Published, 1916.

9Reynolds, David S. Walt Whitman’s America: A Cultural Biography. New York: Vintage Books, 1995: 5.

10Goldman, Emma. Living My Life. 1931. New York: Dover Publications, Inc., 1970: 88.

11Goldman, Emma. Anarchism and Other Essays. 3rd ed. 1917. New York: Dover Publications, Inc., 1969: 79.

12Id., note 10

13Id., note 11

14Ibid., note 5, p. 91

15Marshall, Peter. Demanding the Impossible: A History of Anarchism. London: HarperCollins, 1992: 409.

16Finan, Christopher M. From the Palmer Raids to the Patriot Act: A History of the Fight for Free Speech in America. Boston: Beacon Press, 2007: 18.

17Ibid., note 11 – I could not actually find the book or the essay, but I found a reference to it in this work

Jillian’s Cultural Museum

Posted by jillians in Uncategorized, visitorscripts on December 10, 2009

Whitman and Friends

Two men close to Walt Whitman were Dr. Maurice Bucke and Horace Traubel. Both of the men worshiped Whitman and spent their lives dedicated to honoring his work. They are also considered, Whitman’s disciples[1] for their enthusiastic willingness to spread the works of Whitman and educate others through his literature. In addition, they were also both Whitman’s literary executors, along with his attorney Thomas Harned.

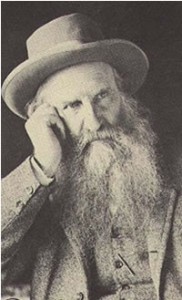

Maurice Bucke

Maurice Bucke

Dr. Maurice Bucke was born in 1837 in Norfolk, England but grew up in Canada after having moved there when he was one year old. When he was sixteen years old he left home and went through near fatal journey that included walking through many mountains in harsh weather. The result was almost fatal and left him without a foot and several lost toes. He was extremely lucky to have survived.

Not long after Bucke recovered from his injuries, he began attending medical school at McGill University. This opportunity came to him through an inheritance and he was fortunate enough to also study in both London and Paris. Upon graduation he worked as a ship surgeon but later settled in the field of psychiatry. He began his practice in Sarnia, Ontario. Soon after he married Jessie Gurd and together they had eight children.

In addition to his work with psychiatry, Bucke was very interested in literature. He was fascinated with Whitman and it is said that he committed much of Whitman’s work to memory. While in Philadelphia on a business trip, Bucke crossed the river into Camden and looked up Whitman. (Could you even imagine doing such a thing today!!) After their initial meeting they became good friends and often traveled together. In the summer of 1880, Whitman even stayed with Bucke at his home in Canada. Bucke worshiped Whitman and Whitman considered Bucke a dependable and loyal friend.

In 1883 they collaborated together on a biography of Whitman. He devoted much of his time and energy to writing, editing and overseeing the publication of Whitman materials.

Bucke also served as Whitman’s medical consultant through the end of Whitman’s life. There is a mass of letters between the two in which Whitman asks for medical advice from Bucke and he treated him directly in the very end of his life. He also helped Whitman to re-write his will and on the day of his death, Bucke was there with him.

After Whitman’s death, Bucke remained committed to their friendship and continued to work on editing several posthumous volumes of Whitman’s writings. He was also one of the editors of Whitman’s Complete Writings. In 1992 a Canadian feature film, Beautiful Dreamers was filmed; it was based on the relationship between Whitman and Bucke, specifically focusing on the 1880 summer visit in Canada.

Maurice lived for ten more years after Whitman died. He slipped on a patch of ice and died from head trauma at 65 in London, Ontario.

Horace Traubel

Horace Traubel

Horace Traubel was born in 1858 in Camden, New Jersey. At the age of twelve he quit school and began working at his father’s stationary school. This prepared him well for a job in print and at sixteen he moved to Philadelphia and became a correspondent for the Boston Commonwealth. It has been said that Traubel is the “epitome of the Progressive Era” (SOURCE). He believed deeply throughout his entire life in the teleological movement of humankind towards its betterment. His personality was such that he was interested in everything for the sake of the things themselves and “he would routinely spend two to three hours per day writing letters to his friends as well as finding and sending them appropriate clippings from other newspapers” (SOURCE).

Traubel’s friendship with Whitman began early in Traubel’s life, while he was still living in Camden as a young boy. They first met when Whitman moved to Camden to live with his brother after his stroke. Because Traubel was only around thirteen years old[2] when they met, neighbors were concerned and their friendship was considered a scandal. Regardless they stayed close even after Traubel moved and in the last years of Whitman’s life Traubel authored the multi-volume biography, Walt Whitman in Camden. Traubel felt as though he was the “spirit child” of Whitman. He later founded, edited and published of The Conservator, a journal dedicated to Whitman.

At the time of Whitman’s death, Traubel had known Whitman for almost twenty years. He dedicated the rest of his own life to keeping Whitman’s work alive and published many Whitman inspired poems. He also published large volumes of his conversations with Whitman that he had written down over the years. A month before he died, Traubel took a final trip to Canada to see a park be dedicated to the honor of Whitman. During the dedication, speaker Helen Keller called for a standing ovation for Traubel in recognition for his tireless efforts to pass along the works of Whitman and for his continuous work in the field of humanity.

Traubel died on May 13, 1919, one year after suffering a serious stroke. He was buried not far from Whitman in the Harleigh cemetery.

Henning, Matthew. Walt Whitman Biography. http://pabook.libraries.psu.edu/palitmap/bios/Traubel__Horace.html

Nelson, Howard. The Walt Whitman Archive. Disciples: Biography, Richard Maurice Bucke. http://www.whitmanarchive.org/criticism/disciples/tei/anc.00247.html

Nelson, Howard. The Walt Whitman Archive. Disciples: Biography, Horace Traubel http://www.whitmanarchive.org/criticism/disciples/tei/anc.00249.html

[1] There were four total disciples. The others were John Burroughs and William Douglas O’Connor

[2] Conflicting accounts of Traubel’s age when having met Whitman; three different sources listed the age as twelve, thirteen and fourteen respectively.

Visitor’s Center Scripts – Whitman’s Family

Posted by bmzreece in Uncategorized, visitorscripts on December 10, 2009

On Walter & Louisa Whitman, and their first 5 children:

Whitman Family Dates

Father: Walter Whitman, Sr. (b. 1789, m. 1816, d. 1855); &

Mother: Louisa Van Velsor Whitman (b. 1795, m. 1816, d. 1873)

Brother: Jesse Whitman (b. 1818, d. 1870)

Walt Whitman (b. 31 May 1819, d. 26 March 1892)

Sister: Mary Elizabeth Whitman (b. 1821, d. 1899)

Sister: Hannah Louise Whitman (b. 1823, d. 1908)

Brother: Andrew Jackson Whitman (b. 1827, d. 1863)

Brother: George Washington Whitman (b. 1829, d. 1901)

Brother: Thomas Jefferson Whitman (b. 1833, d. 1890)

Brother: Edward Whitman (b. 1835, d. 1892/1902 [some sources differ])

The second son [and second child overall] of Walter and Louisa Whitman [nee Van Velsor], Whitman had 5 brothers and 2 sisters.

Walt’s father, the carpenter Walter Whitman, died in 1855, and thus did not live to see any of Walt’s aesthetic work. Walt, however, did not believe his father would have appreciated Walt’s work any more than did the rest of Walt’s family [which was allegedly very little]. Walt believes his father would have still accepted and loved him, but not understood him, much as with the rest of his family (Schmidgall 34).

Walt loved his mother, Louisa Van Velsor Whitman, and spoke much more of her than of his father. Walt describes himself and his mother as “great chums” and speaks highly of her belief in his ability (Schmidgall 33), though she never appreciated nor understood Leaves of Grass.

Walt identifies his family background as Quaker, though he describes his father more as a “friend” or “follower” of a Quaker figure and his mother Louisa as having Quaker “leanings,” “sympathies,” and “tendencies,” rather than as practicing Quakers (Schmidgall 34).

Little is known about Jesse Whitman aside from his being a sailor and his death. Even Horace Traubel, famously close to Walt, knew little of Jesse other than that he died of an aneurism on March 21, 1870 while a patient at the Kings County Lunatic Asylum in Flatbush, Long Island [an event about which Walt was informed by a letter sent the next day]. Traubel alleges that Walt never spoke of Jesse even when showing the letter to Traubel (Schmidgall 37).

Carrying on the Dutch heritage of her mother, Mary Whitman married a mechanic by the name of Van Nostrand in 1840 and lived in Greenport, Long Island. Walt visited her frequently but, according to Traubel, hardly spoke of her in conversation. In the conversation with Traubel in which Walt does speak of Mary, he refers to her frailty resulting from rheumatism, though she had been full of energy as a child (Schmidgall 34-35).

Hannah Whitman [also Hanna], often referred to in family letters as “Han” or “Hann,” seems to be often thought of but seldom visited or visiting. Hannah lived in Burlington, Vermont with her husband, Mr. Heyde. This marriage did not seem to be a happy one, as Hannah often would express frustration “that Heyde could be so amiable with others and hateful to her” (Pollak 226). Heyde appears an unfortunate real life Mr. Hyde.

Andrew Jackson Whitman is the least-mentioned of Walt’s three brothers named after presidents. His wife, however, was quite nefarious: She is referred to as a “foul slut” who became a prostitute after he died (Gohdes viii).

In general, Walt was not particularly close with his family. He says, “A man’s family is the people who love him—the people who comprehend him,” and explains that his family never understood him or his work. With regard to his blood family, he sees himself as “isolated” or as “a stranger in their midst”; instead, he sees those close to him [Traubel, the O’Connors and others] as his true family (Schmidgall 33).

Bibliography

Gohdes, Clarence and Rollo G. Silver, eds. Faint clews & indirections; manuscripts of Walt Whitman and his family. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 1949.

Pollak, Vivian R. The Erotic Whitman. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000.

Schmidgall, Gary, ed. Intimate with Walt : selections from Whitman’s conversations with Horace Traubel, 1888-1892. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2001.

Visitors Center Script: Whitman and the Beats

Posted by lizmoser in beats, ginsberg, kerouac, Uncategorized, visitors' center, visitorscripts on December 3, 2009

Whitman and the Beats

Peter Orlowsky and Allen Ginsberg

The Beat Generation–poets of the 1950-60’s who rejected mainstream American culture in favor of poetic and spiritual libration. The Beat poets experimented with drugs and alternative forms of sexuality, and developed an interest in Eastern thought and spirituality. Among their most famous works: Howl by Allen Ginsberg, On the Road by Jack Kerouac and William S. Burrough’s Naked Lunch.

Jack Kerouac was a proponent of stream-of-consciousness writing, a style that Ginsberg later adopted. This can be compared to Whitman’s Specimen Days and his in-the-moment “unedited” prose of detailing Civil War events from the capitol.

Ginsberg also uses long-lines in an approach to capture the rhythm of jazz with the length of a breath–Howl and other poetry is particularly well-suited to oral recitation:

I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by

madness, starving hysterical naked,

dragging themselves through the negro streets at dawn

looking for an angry fix,

angelheaded hipsters burning for the ancient heavenly

connection to the starry dynamo in the machinery of night,

who poverty and tatters and hollow-eyed and high sat

up smoking in the supernatural darkness of

cold-water flats floating across the tops of cities

contemplating jazz…

Howl by Allen Ginsberg

Whitman was among the first to popularize long lines of verse, which the Beats readily adopted for its poetic power and oracular quality.

Whitman and the Beats are similar in more than just style–they share many poetic themes and political beliefs.

One of these is a distaste for American materialism. The Beats struck down mainstream culture for its materialism, embracing spontaneity and liberation over conventionality. Whitman also criticized materialist culture, stressing an appreciation of the simpler things in life, among them, the beauty of nature and the human body.

The Beats also shared Whitman’s fascination with the sexualized male form. Although Whitman never admitted to homosexuality, Ginsberg felt no shame with his own sexual relations with Peter Orlowsky, his life-long partner.

Whitman and the Beats were both poets that were involved with the change of the nation’s character in the face of war. Whitman still retained a somewhat positive outlook on America throughout the Civil War, even after all the casualties that he witnessed in the hospitals. Ginsberg and the Beat poets adopted a far more grim approach, writing about the alienation of men and women and the destruction of individuals of great character by malign societal control and conformity.

Nevertheless, both poets awoke America with their radical poetry and politics and shaped the cultural, political and literary scene for decades to come.

Jack Kerouac at a reading

Christine’s blog, Whitman and the Equality of Women

Jessica’s blog, Whitman, Bucke and Carpenter

Visitors’ Center Script: Whitman’s Disciples, part three

Posted by emilym in Uncategorized, visitors' center, visitorscenter, visitorscripts, visitorsscripts, ww20 on December 3, 2009

My first disciple is John Burroughs. Like Kevin explained about Maurice Bucke, Burroughs imagined himself a friend and disciple of Whitman before they had even met. Burroughs acts as a loyal friend and defender to Whitman two years prior to meeting him: “In 1862 he had frequently visited Pfaff’s beer cellar, a bohemian watering hole and the center of literary life in Manhattan. There Burroughs championed Whitman in literary arguments, anticipating at every moment a meeting with the poet himself” (Sarracino). This is a behavior Burroughs would continue to exhibit toward Whitman after they became friends and throughout their friendship.

In 1864 Burroughs and Whitman met, by chance, in Washington D.C. Whitman was heading toward the army hospital, so he invited the unemployed Burroughs along. Burroughs got a job nursing the wounded, but he didn’t have the stomach for it and quickly left. Even though Burroughs’s employment at the hospital didn’t last, his friendship with Whitman would last until the poet’s death—and beyond.

Burroughs held several odd jobs, none of which lasted long to the chagrin of his wife, Ursula, but he always wanted to write. Under Whitman’s tutelage and encouragement, Burroughs developed his writing skills, sending pieces to magazines while working at his day jobs. Eventually, with Whitman’s help, he discovered his niche in writing about nature; he had an amazing eye for the details of nature, which in turn inspired Whitman to sharpen his eye for his poetry. Once again, Whitman’s relationship with his friend/disciple involved giving and receiving advice: It was a true friendship, not a one-sided relationship.

Burroughs’s behavior also reveals a proto-feminist perspective in Whitman. When Burroughs and his wife were having marital problems, Whitman sided with Ursula, always. He chastised Burroughs for his infidelity and insisted Ursula’s lack of sexual interest in Burroughs was a result of his failings to earn her love. This is a very interesting defense of the wife of a friend. Naturally, Ursula was a good friend of Whitman, though not a disciple.

There is also a quasi-sexual element between Burroughs and Whitman. I’m not claiming that they were lovers, though it is a possibility that can never be proven, but I thought it was very interesting that Burroughs referred to the love of his life (not Ursula) as “Whitmanesque.” She could have been described as beautiful, or intelligent, or any other adjective, but Burroughs chooses to describe her in similar terms as his dead friend. Clearly, this is an indication of the love and devotion Burroughs felt for Whitman, which persisted after the poet’s death and remained until his own death.

Like Bucke, Burroughs also wrote a biography of Whitman, Notes on Walt Whitman, which was also edited and partially written by Whitman. It also isn’t very objective. In his introduction, Burroughs includes inflated language about how Whitman isn’t appreciated in his own time, but will one day be absorbed by America—in the way Whitman sought to be absorbed.

Click here for Notes on Walt Whitman

My next disciple is Horace Traubel who, unlike the previous disciples, was only fourteen when he met Whitman in Camden in 1873. Because of the vast age difference between Traubel and Whitman, there were whisperings and rumors of a sexual nature among the neighbors. Again, there is no evidence of anything sexual in their relationship, but there is a quasi-sexual element present between them.

Traubel viewed himself as Whitman’s son, and he played the role of a devoted son—even after Whitman’s death. He tended to Whitman as he was ailing, carefully writing a journal/book With Whitman in Camden. In his note to readers in With Whitman in Camden, Traubel explains his motivation for writing the book and how it is designed to honor Whitman’s wishes.

Click here for the first part of With Whitman in Camden

Traubel writes about how he will tell the truth about Whitman in his final months because that is how the poet wanted to be remembered.

Growing up, Traubel was increasingly interested in reform and read Leaves of Grass as having a socialist agenda. He received confirmation from a reluctant Whitman. In any event, Traubel’s work was to take what he felt Whitman started in Leaves of Grass and extend it to be even more radical with a major socialist slant. Traubel wrote his own books, but they can be read as “socialist refigurings of Whitman’s work” (Folson). His work as a radical reformist made it difficult for him to find and keep a good job. So, he lived a relatively impoverished life.

A few days before he died in 1919, Traubel saw a vision of Walt Whitman beckoning him to the afterlife. Again, this is an example of Whitman having the divine meaning of a demigod for his disciples. Traubel is buried in Harleigh Cemetery close by Whitman’s tomb—like a son would be buried nearby a father.

Works Cited

Folsom, Ed. “Disciples: Biography, Horace Traubel.” The Walt Whitman Archive, 2009. Web. 28 Nov. 2009.

Sarracino, Carmine. “Disciples: Biography, John Burroughs.” The Walt Whitman Archive, 2009. Web. 29 Nov. 2009.

Adam’s visitors center script–Whitman disciples–Sadakichi Hartmann

Posted by adamb in Uncategorized, visitorscripts on December 3, 2009

SADAKICHI HARTMANN

While doing a search project about Whitman’s racism during his Camden years, I came across an interesting story about a Whitman disciple named Sadakichi Hartmann. Surprisingly, Reynolds does not mention Hartmann in his book.

Whitman’s admiration for Asian civilizations is apparent in his work. In “Passage to India,” he suggests that the complete of the transcontinental railroad as the completion of Columbus’ voyage, and America as a connection between the great civilizations of Europe and Asia. Whitman had a circular view of civilization–Asia as the beginning of civilization, Europe as the absolute end. In “Passage to India,” he even advocates interracial marriage.

Passage to India!

Lo, soul, seest though not God’s purpose from the first?

The earth to be spann’d, connected by network,

The races, neighbors, to marry and be given in marriage,

The oceans to be cross’d, the distant brought near,

the lands to be welded together (Whitman, 532)

Whitman was horrified by the Chinese Exclusion Act passed by Congress in 1882. Whitman threatened to denounce his citizenship in protest saying, “In that narrowest sense, I am not an American—count me out” (Li, 181). He made his view on immigration clear telling Traubel,

“Restrict nothing—keep everything open: to Italy, to China, to anybody. I love America, I believe in America, because her belly can hold and digest all—anarchist, socialist, peacemakers, fighters, disturbers or degenerates of whatever sort—hold and digest all. If I felt that America could not do this I would be indifferent as between our institutions and any others. America is not all in all—the sum total: she is only to contribute her contribution to the big scheme” (Traubel 1:113).

Whitman’s contact with Asian immigrants was rather limited since Camden had only two Chinese-Americans in 1880 and fifty-four in 1890. By 1895, the city directory listed 29 Chinese-run laundries. As their numbers grew, so did anti-Chinese hatred. In the late 1890s, white locals stoned, burned, and dynamited Chinese laundries. Chinese were frequently harassed, beaten, and on a few occasions, murdered (Dorwart, 91).

Whitman’s only known contact with an Asian American in Camden was with Sadakichi Hartmann. He was born in Japan in 1867 to a German father and Japanese mother and raised mostly in Germany. When his father disinherited him for refusing to attend military school, Hartmann immigrated to California. There, he was harassed on suspicion of being a Japanese agent. He moved to Philadelphia to live with an uncle and studied briefly at the Spring Garden Institute. A “dusty bookseller” encouraged Hartmann to visit the poet in Camden telling him, “He is living across the river in Camden and likes to see all sorts of people.” Hartmann visited the poet frequently and became a Whitman disciple, founding a Whitman club. Their relationship soured when Whitman told Hartmann, “There are so many traits, characteristics, Americanisms which you would never get at . . . After all, one can’t grow roses on a peach tree” (Hartmann, 8). Whitman was furious when Hartmann published some of Whitman’s catty remarks about contemporary writers in the New York Herald (Li, 184). The annoyed Whitman questioned Hartmann integrity to Traubel.

“In is in him something basic—something that relates to origins . . . He is a biggish young fellow – has a Tartic face. He is the offspring of a match between a German—the father—and Japanese woman: has the Tartic makeup. And the Asian craftiness, too—all of it!” (Traubel 5:38).

Just before Whitman’s death, Hartmann and his wife visited Whitman and the two made amends. When he learned of Whitman’s death, Hartmann was in New York and unable to afford the train fare to attend Whitman’s funeral. He went to Central Park and “held a silent communion with the soul atoms of the Good Grey Poet, of which a few seem to have wafted to me on the mild March winds” (Hartmann, 50).

Like many of Whitman’s disciples, he wrote a short book detailing his interactions with Whitman. In 1894, he wrote Conversations with Walt Whitman. Hartmann wrote became an early proponent of literary Modernism in the twentieth century. He wrote several volumes of poetry in the early and was one of the first to write English language haikus. He died in 1944.

Works Cited

Dorwart, Jeffrey M. Camden County: the making of a metropolitan community, 1626-2000. New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 2001.

Hartmann, Sadakichi. Conversations with Walt Whitman. New York: Gordon Press, 1972.

Li, Xilao. “Walt Whitman and Asian American Writers.” Walt Whitman Quarterly Review 10.4 (1993): 179-194. Print.

Christine’s Visitor’s Center Script for 12/3

Posted by pieruccm in Uncategorized, visitorscripts on December 3, 2009

Group #2: Whitman’s involvement with/effect on social and/or political movements. My section involves his position on the women, sexual orientation, and slavery (although each section takes a look at a specific aspect of each of these broad ideas). I choose these three in particular because a lot of Whitman’s poetry is a reflection of some sort on all of them. See below:

Whitman’s view on Equality of Women (specifically sexuality)…

Joann Krieg states, “Whitman has escaped feminist attack largely because the many gestures of inclusiveness – of race, class, and gender – in the poems confirm his assertion that he was ‘the poet of the woman the same as the man’” (Krieg, 36). I think it is fair to say that not only did Whitman’s writing push for equality among all peoples, but also that his writing reflected, at least somewhat, his personal views on the equality between men and women. Although Whitman believed that the ideal woman was above all others a mother, he still had strong views towards women’s sexuality, including prostitution. Whitman’s position on the topic of prostitution was stationed right among other progressive thinkers of the time when discussions regarding sex, gender, urbanity, and the health of the individual or society were “hot” topics. Krieg says, “Whitman’s insistence on the perfect equality of women with men and his celebration of female sexuality were unusual, but he was far from unique in holding such ideas. Rather, he was part of a wide movement among more advance thinkers that concentrated on all aspects of physicality, including sexuality” (Krieg, 37). In fact, Whitman never officially opposed prostitution on the grounds of morality, but instead he opposed it because he knew of the venereal diseases that could be linked with the behavior, as well as the breakdown of the ideal family. Still, Whitman viewed these women with compassion because he felt that they had been victimized by society for what he called the “social disease”. A particular instance when Whitman showed his compassion towards the prostitutes was an experience he had in New York, watching a police raid of over 50 prostitutes arrested and carried away. Another example of Whitman’s connection with these social “outsiders” is directly seen in his poem, “To a Common Prostitute”, where “he asserts that the prostitute is a part of nature and not to be excluded, spatially or otherwise, by the word or edict of man” (Krieg, 41).

Whitman’s view of Democracy and Homosexuality…

In the late nineteenth century, attitudes regarding same-sex relationships were shifting due to medical discussions that formulated theories that homosexuals were a distinct biological type. At the same time, the policies of the Communist Party of the U.S. had little tolerance of same-sex relationships. Therefore, the appeal of Whitman’s masculinity was highly complicated due to the question of his sexual orientation. When Whitman first released the “Calamus” poems in 1860, he dedicated them to the progression of exploring relations between men, as an attempt to “regenerate republican virtue” (Garman, 100). Essentially, Whitman’s purpose was to absolutely refuse to specify the sex of the partner of whomever he speaks in “Whoever You Are Holding Me Now in Hand” because it “implies that an artificially delineated heterosexuality would be undemocratic because it would restrict the natural expression of love and pleasure solely to male-female relationships and would prevent its fair exchange between same-sex partners. Democracy could not make distinctions of any kind, particularly when it came to sexual matters” (Garman, 101). Whitman further complicates his indecisiveness through the difference in tone between the “Calamus” poems, which are frankly homosexuality and what seems to be a glorification of the behavior, and the “Children of Adam” section of Leaves of Grass, which could most definitely be read as obscene descriptions of heterosexual relations. On the whole, Whitman believed that it was unnecessary to conform to one individual “type” and this also carried into his poetry, where he did not conform to typical poetic conventions. He even so far as claimed that he fathered six illegitimate children to disprove others’ claims about his homosexuality.

Whitman’s view on Slavery and Democracy…

While working in New Orleans in 1848, Whitman was working as a reporter for the Daily Crescent, writing about “local color and charm as seen through Yankee eyes” (Gambino, 14). After returning to New York, Whitman began working for Brooklyn’s Daily Freeman, this time as editor. This editorial was the nation’s main face to the Free Soil Movement at the time, whose motto was, “Free soil, free labor, free men!” and Whitman retained his advocacy of this movement to the point that he was fired from his previous position with Brooklyn Daily Eagle before leaving for New Orleans. On the other hand, Whitman believed that white reproduction as a foolproof plan of minimizing social advancements against African Americans who were recently emancipated. Consequently, involvement in the Free Soil Movement caused unforeseen problems. Whitman came to hate the abolitionists, who ultimately had fight among themselves, as well as hating “the hypocritical and corrupt men of the Democratic Party” (Gambino, 14). Whitman expresses his true feelings of the flaws of the American democracy of the time in what Gambino calls a “lengthy, scathing critique”, called Democratic Vistas (1871) The flaws, to be precise, would be the failings of the American people and culture.

Works Cited

Gambino, Richard. “Walt Whitman.” The Nation. July 21/28, 2003. Page 14.

Garman, Bryan K. “‘Heroic Spiritual Grandfather’: Whitman, Sexuality, and the American Left, 1890-1940.” American Quarterly. Volume 52, Issue 1. 2000. Pages 100-1.

Krieg, Joann P. “Walt Whitman and the Prostitutes.” Literature and Medicine. Volume 14, Issue 1. 1995. Pages 36-7, 41.

The links below are the other members of my group, Jessica and Liz, who have researched other aspects of Whitman’s involvement in social and political movements/affairs:

Visitor’s Center Script

Posted by jessicaa in Uncategorized, visitorscripts on December 2, 2009

Although Walt Whitman is now a highly respected and acclaimed writer, he was writing during a time that was very different to today’s society. His thoughts on democracy, spirituality, and sexuality were massively forward thinking for their time, but were also highly influential. Those who had a positive reaction to Whitman’s work went on to use his ideas to create new works of poetry and prose that attempted to influence society in the manner in which Whitman intended. Two of these individuals are Dr. Richard M. Bucke (R.M. Bucke) and Edward Carpenter.

R.M. Bucke was a Canadian psychiatrist who greatly admired Whitman. He was the author of Whitman’s biography, and also wrote many other works including Man’s Moral Nature and Cosmic Consciousness. The ideas in Bucke’s writing were heavily inspired by Whitman’s work, which can be seen when assessing the passages of Bucke’s prose. In his article “The myth of a Canadian Boswell: Dr. R.M. Bucke and Walt Whitman” S.E.D. Shortt says of Bucke, “his ideas, he believed, simply derived from years of empirical study of Walt Whitman’s character and his principal work, ‘Leaves of Grass.’ Indeed, Bucke correctly saw a continuity in his scholarship to which the notion of cosmic consciousness was merely the logical capstone” (Shortt 56). Bucke believed that through his study of Whitman, and his understanding of Whitman’s philosophy, his own writings were adding to the same body of work, and were furthering the influence of these ideas onto society.

Bucke was part of a group of scholars who would gather to enjoy many esteemed authors, including Browing, Wordsworth, and specifically Whitman. In Bucke’s book Cosmic Consciousness he recounts one such gathering where, after leaving, he had an experience of absolute transcendence which he attributes to the recollection of Whitman’s work. Shortt quotes the experience as follows:

“…Into his brain streamed one momentary lightning-flash

of the Brahmic Splendor which has ever since lightened his life; upon

his heart fell one drop of Brahmic Bliss, leaving thenceforward for

always an after taste of heaven. Among other things he did not come

to believe, he saw and knew that the Cosmos is not dead matter but

a living Presence, that the soul of man is inmortal, that the universe

is so built and ordered that without any peradventure all things work

together for the good of each and all, that the foundation principle

of the world is what we call love and that the happiness of everyone

is in the long run absolutely certain…” (Shortt 56-57).

The ideas that all things in the universe work together for the good of everything is exactly the same idea that Whitman conveys in many of his works, specifically Leaves of Grass. In “Song of Myself” Whitman says, “I resist anything better than my own diversity, and breathe the air and leave plenty after me, and am not stuck up, and am in my place. The moth and the fisheggs are in their place, the suns I see and the suns I cannot see are in their place, The palpable is in its place and the impalpable is in its place” (Whitman 43). The idea here is that all of these things have their role in the universe, and that all of these parts make up the living breathing thing that is the universe. This idea is exactly what Bucke was expanding upon in Cosmic Consciousness, in attempt to influence social thought on spirituality and the nature of man. In Part I of Bucke’s Cosmic Consciousness he wrote, ““that the universe is so built and ordered that without any peradventure all things work together for the good of each and all, that the foundation principle of the world is what we call love and that the happiness of everyone is in the long run absolutely certain” (Bucke in Shortt). Bucke was trying to further pass on to society the ideas from Whitman’s work that inspired him.

However Bucke was not the only writer at this time so powerfully influenced by Whitman. At the same time Edward Carpenter was also enamored with Whitman’s philosophies, and after meeting with Whitman on several occasions Carpenter recorded his experiences and published Days with Walt Whitman. Carpenter was influenced by Whitman’s ideas of democracy, as well as his social and spiritual claims, and went on to publish a book titled Towards Democracy, which was a collection of poems expanding on Whitman’s ideas of democracy and equality. In this piece Carpenter writes, “Freedom! At Last! Long sought, long prayed for – ages and ages long..” (Carpenter 3). Many of the poems speak of democracy in much the same positive light as Whitman does. As influenced by Whitman, Carpenter’s writings on “sexuality, religion, aesthetics, and a range of political topics won him international renown as a progressive thinker” (jrank). Carpenter became an active speaker on social issues such as environmental rights and women’s suffrage. Openly homosexual, Carpenter was inspired by Whitman to speak out about his sexual preferences and be an example for society. “In his emulation of Whitman, Carpenter became one of the first of many disciples, spreading Whitman’s message into another country and another century” (Kantrowitz).

It can be seen that Whitman had a very strong effect on Bucke and Carpenter, and many other writers who came after. Whitman’s philosophies of religion, democracy, sexuality, and social interactions paved the way for many other writers to write openly about social issues that were not commonly explored. Both of these writers were so inspired they not only wrote on similar topics as Whitman, but wrote about Whitman himself, which further shows their respect and admiration for Whitman as a poet, and as a social influence.

Works Cited

Carpenter, Edward. “Towards Democracy”. Kessinger Publishing, LLC (May 31, 1942)

Kantrowitz, Arnie. “Carpenter, Edward [1844-1929]”. J.R. LeMaster and Donald D. Kummings, eds., Walt Whitman: An Encyclopedia (New York: Garland Publishing, 1998), reproduced by permission. http://www.whitmanarchive.org/criticism/…

Shortt, S.E.D. “The myth of a Canadian Boswell: Dr. R.M. Bucke and Walt Whitman”. Canadian Bulletin of Medical History, Vol 1, No 1 (1984)

Whitman, Walt. “Whitman: Poetry and Prose”. Penguin Books USA Inc. 1996. Literary

Classics of The United States, Inc. New York, N.Y.

“Edward Carpenter Biography – (1844–1929), Days with Walt Whitman, Towards Democracy, England’s Ideal “http://www.jrank.org/literature/pages/3549/Edward-Carpenter.html#ixzz0YMBUMZL3

http://lizmoser.lookingforwhitman.org