Second Mexican Empire

Mexican Empire | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1864–1867 | |||||||||

| Motto: Equidad en la Justicia "Equity in Justice"[citation needed] | |||||||||

.svg/250px-Second_Mexican_Empire_(orthographic_projection).svg.png) Territory claimed by the Second Mexican Empire upon establishment | |||||||||

| Status | Independent monarchy,[1][2][3] Client state of France | ||||||||

| Capital | Mexico City | ||||||||

| Common languages | Spanish | ||||||||

| Government | Federal parliamentary constitutional monarchy | ||||||||

| Emperor | |||||||||

• 1864–1867 | Maximilian I | ||||||||

| Regency | |||||||||

• 1863–1864 | Juan Almonte, José Salas, Pelagio de Labastida | ||||||||

| Prime Minister[4] | |||||||||

• 1864–1866 | José María Lacunza | ||||||||

• 1866–1867 | Teodosio Lares | ||||||||

• 1867 | Santiago Vidaurri | ||||||||

| Historical era | New Imperialism | ||||||||

| 8 December 1861 | |||||||||

• Maximilian I accepts Mexican crown | 10 April 1864 | ||||||||

• Emperor Maximilian I executed | 19 June 1867 | ||||||||

| Currency | Peso | ||||||||

| ISO 3166 code | MX | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | Mexico | ||||||||

The Second Mexican Empire (Spanish: Segundo Imperio Mexicano), officially the Mexican Empire (Spanish: Imperio Mexicano), was a constitutional monarchy established in Mexico by Mexican monarchists in conjunction with the Second French Empire. The period is sometimes referred to as the Second French intervention in Mexico. French Emperor Napoleon III, with the support of the Mexican conservatives, clergy, and nobility, established a monarchist ally in the Americas intended as a restraint upon the growing power of the United States.[5] It has been viewed as both an independent Mexican monarchy[1][6][7] and as a client state of France.[8][9] Invited to become emperor of Mexico by Mexican monarchists who had lost a bloody civil war against Mexican liberals was Austrian Archduke Maximilian, of the House of Habsburg-Lorraine, who had ancestral links to rulers of colonial Mexico. His wife and empress consort of Mexico was the Belgian princess Charlotte of the House of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, known in Mexico as "Carlota".

The invading French army was able to gain control of the central portion of the nation but supporters of the Mexican Republic continued to wage war against the Empire with its army as well as guerrilla bands. Although President Benito Juárez was forced to abandon the capital of Mexico City, he never left the national territory, despite having to relocate his northern base several times as Imperial forces sought to expand their territorial control. Maximilian's regime garnered recognition from some European powers, including Great Britain and Austria, but it was not recognized by the United States. At the time of the invasion, the U.S. was embroiled in its civil war (1861–65) against secessionist Confederate States of America. The U.S. continued to recognize the Republican government as legitimate and exerted diplomatic pressure on France to withdraw, but it did not send material aid.[10] With Northern U.S. states' defeat of the secessionist Southern states in 1865, the political calculus for Napoleon III changed, since his support for the Mexican monarchy was predicated on a weakened U.S. and continued existence of the Confederate States. In 1866, Napoleon III began withdrawing French troops, which had propped up Maximilian's regime, and refused more funding for the Mexican monarchy. Maximilian's liberal ideals had alienated him from his conservative supporters. He gained limited support from moderate liberals, affirming much of the legislation on the liberal Reform, and attempted to implement other reforms, which did not come to fruition during his short reign. Although the military situation quickly became hopeless for the Mexican empire, Emperor Maximilian refused to abdicate and leave with the departing French troops. Republican forces captured the Emperor and his two leading Mexican generals in Querétaro. The Empire came to an end on 19 June 1867, when Maximilian was executed by firing squad, along with his generals Mejía and Miramón, after being tried by the Mexican Republic.

History[edit]

Post-independence Mexico was briefly a monarchy, lasting just over a year, when the emperor abdicated and went into exile, and a federated republic was established in 1824. The idea of monarchy persisted and in 1861, Mexican conservatives and emperor Napoleon III of France brokered a deal to create a new monarchy in Mexico, with Archduke Maximilian agreeing to become emperor, with the military and financial backing of France. The French army ousted Mexican President Benito Juárez from the capital and Maximilian and his wife Carlota arrived in Mexico in 1864. The regime lasted so long as French troops and money supported it, but rapidly fell once Napoleon III withdrew that aid.

Mexican monarchism[edit]

After a decade of warfare (1810–21) Mexico gained its independence under the leadership of American-born, royalist military commander turned insurgent Agustín de Iturbide, who united insurgents and Spaniards under the Plan of Iguala. The Plan promised independence for Mexico as a monarchy (First Mexican Empire), and also invited a member of Spanish royalty to assume the newly established Mexican throne. After the offer was refused by the Spanish royals, congress searched for an emperor within the newly independent country. After an armed demonstration by Iturbide's regiment of the Army of the Three Guarantees, the Mexican congress elected the Mexican-born military officer and leader of independence as the first Mexican emperor. Although during the independence struggle, Mexicans considered the idea of republicanism, "monarchy was the default position." Iturbide rule as emperor lasted less than two years, but the height of his power lasted only six months.[11] in his attempts to govern, struggled to find funds to pay the army and the rest of the government, and closed congress, accusing representatives of obstructionism and idleness, eventually leading to a military uprising against Iturbide and his subsequent abdication. The idea of a monarchy had been discredited for a time, but the idea did not disappear, as many of the disorders associated with the First Empire continued well into the Republican era.

French observers began expressing interest in the idea of a Mexican monarchy as early as 1830. Lorenzo de Zavala claimed that in that year, he was approached by a foreign agent hoping to recruit him in a plan to place an Orléans monarch upon a Mexican throne.[12] In 1840 José María Gutiérrez Estrada wrote a monarchist essay endorsing the idea of a legitimate European monarch being invited to govern Mexico. The pamphlet was addressed to the conservative president Bustamante, who rejected the idea.[13] French diplomats tended to sympathize with the Conservatives in Mexico, Victor de Broglie opining that monarchy was a form of government more suited to Mexico at the time and François Guizot giving a positive review of Estrada's pamphlet. [14]

A monarchist faction in 1846 promoted the idea of establishing a foreign prince at the head of the Mexican government, and president Paredes was viewed as being sympathetic to monarchism, but the project was not pursued due to the more pressing matter of the American invasion of Mexico. The candidate being proposed at the time was the Spanish prince, Don Enrique. [15]

The last official Mexican effort to explore the possibility of establishing a monarchy occurred under the presidency of Santa Anna in the early 1850s, when conservative minister Lucas Alamán directed monarchist diplomats José María Gutiérrez de Estrada and Jose Manuel Hidalgo to seek a European candidate for the Mexican throne. With the overthrow of Santa Anna's government in 1855, these efforts lost their official support and yet Estrada and Hidalgo continued their efforts independently.

French invasion and establishment of monarchy[edit]

The international situation shifted making a French invasion and establishment of a monarchy in Mexico a real possibility. Conservative Mexican politicians Estrada and Hidalgo managed to get the attention of French emperor Napoleon III, who came to support the idea of reviving the Mexican monarchy and re-establishing a French imperial presence in the Americas. Prior to 1861 any interference in the affairs of Mexico by European powers would have been viewed in the U.S as a challenge to the Monroe Doctrine. In 1861 however, the U.S. was embroiled in its own conflict, the American Civil War, which made the U.S. government powerless to intervene directly, but it never condoned the French invasion or the regime it established. On July 1861 Mexican President Benito Juárez declared a two-year moratorium on Mexican debt to France among other nations, much of it loans contracted by the defeated rival conservative government, Napoleon finally had a pretext for armed intervention. Encouraged by his Spanish-born wife, Empress Eugenie, who saw herself as the champion of the Catholic Church in Mexico, Napoleon III took advantage of the situation. Napoleon III saw the opportunity to make France the great modernizing influence in the Western Hemisphere, as well as enabling the country to capture the South American markets. To give him further encouragement, his half-brother, the duc de Morny, was the largest holder of Mexican bonds on which President Juárez had suspended payment.

French troops landed in December 1861, and began military operations in April 1862. They were eventually joined by conservative Mexican generals who had never been entirely defeated in the War of Reform.[16] After Charles de Lorencez's small expeditionary force was repulsed at the Battle of Puebla on 5 May 1862, delaying the French push to capture the capital. Reinforcements were sent and placed under the command of Élie Forey. The capital was not taken until a year later in June 1863 and the French now sought to establish a Mexican regime under its influence. Forey appointed a committee of thirty-five Mexicans, the Junta Superior, who then elected three Mexican citizens to serve as the government's executive: Juan Nepomuceno Almonte, the natural son of independence leader José María Morelos; José Mariano Salas, and Pelagio Antonio de Labastida. In turn this triumvirate then selected 215 Mexican citizens to form together with the Junta Superior, an Assembly of Notables.[17]

The Assembly met in July 1863 and resolved to invite Archduke Maximilian to be Emperor of Mexico. The title of the executive triumvirate was formally changed to the Regency of the Mexican Empire. An official delegation left Mexico and arrived in Europe in October. In Europe, Maximilian was continuing negotiations with Napoleon III. He requested a plebiscite to ratify the establishment of the Empire by the Assembly of Notables. The referendum was granted, and the result was affirmative; critics viewed it as illegitimate and suspect due to being conducted by the occupying French authorities. Maximilian also rebuffed French efforts to outright annex the state of Sonora, an act which would later be used in his trial to defend against the Republican government's accusation that Maximilian had been a French puppet.[18] Maximilian formally accepted the crown on 10 April 1864, and set sail for Mexico, arriving in Veracruz on 28 May and reaching the capital on 12 June.

Although French troops controlled the center of the country, including the port of Veracruz, the capital Mexico City, and other major cities, President Juárez remained in the national territory, moving north. In the countryside, republican guerrillas waged warfare against the French troops and their Mexican army allies.

Maximilian's reign[edit]

Maximilian and Carlota were crowned at the Cathedral of Mexico City.[19][20][21] On his arrival in the summer of 1864 Maximilian declared a political amnesty for all liberals who wished to join the Empire, and his conciliation efforts eventually won over some moderate liberals such as José Fernando Ramírez, José María Lacunza, Manuel Orozco y Berra, and Santiago Vidaurri.[22] His first priorities included reforming his ministries and reforming the Imperial Mexican Army, the latter of which was impeded upon by Bazaine in an effort to consolidate French control of the nation.[23]

Maximilian alienated conservative supporters who had brought him to the throne. In December the pope's representative, Papal Nuncio Francesco Meglia, arrived in order to arrange a concordat with the Empire to revise the Reform laws previously passed by the liberal Mexican government. Liberal laws and the Constitution of 1857 nationalized Catholic Church property. Although a Catholic, politically Maximilian was a liberal. The Papal Nuncio's demands that the emperor restore the power and privileges of the Catholic Church resulted in Maximilian confirming the liberal reform laws regarding freedom of religion and the nationalization of Church property. In taking this action, the emperor alienated the Catholic hierarchy and many Mexican conservatives, who had backed Maximilian becoming emperor. The confrontation over the role of the Church produced an atmosphere of crisis. In Mexico City, the disorder was considerable and Maximilian feared a revolt by Mexican army generals on whom he had relied. He sent Generals Miguel Miramón and Leonardo Márquez out of the country and disbanded the small Mexican army that had supported the empire.[24]

Maximilian took a number of solo state trips through the nation while Empress Carlota reigned as regent. He went to Querétaro, Guanajuato, and Michoacán, giving public audiences and visiting officials, even celebrating Mexican independence by commemorating the Cry of Dolores in the actual town where it took place.[25]

Deteriorating imperial military situation[edit]

French troops had been able to take considerable Mexican territory from republican forces while the U.S. was embroiled in its civil war, but in April 1865, Union forces defeated the secessionist Confederate States of America after four years of bloody combat. The U.S. government was reluctant to enter a direct conflict with France to enforce the Monroe Doctrine prohibiting European powers in the Americas, but official U.S. government sympathy remained with Mexican president Benito Juárez. The U.S. government had refused to recognize the Empire and also ignored Maximilian's correspondence.[26] In December 1865, a $30 million private American loan was approved for Juárez, indicating a confidence that he would return to power, and American volunteers joined the Mexican republican troops.[27] An unofficial American raid occurred near Brownsville, and Juárez's minister to the United States, Matías Romero, proposed that General Grant or General Sherman intervene in Mexico to help the republican cause.[28] The United States refrained from direct military intervention, but it put diplomatic pressure on France to leave Mexico. [29]

A concentration of French troops in the northern republican strongholds of Mexico led to a surge of republican guerrilla activity in the south. While French troops controlled major cities, guerrillas continued to be a major military threat in the countryside, which affected imperial military planning. Troops had to be concentrated and operate in areas where guerrillas could not easily cut them off and eliminat them. In an effort to combat the increasing violence and in a belief that Juárez was outside of the national territory, Maximilian in October signed an order at the urging of the French military commander Bazaine, the so-called "Black Decree." It mandated the court martial and execution of anyone found either aiding or participating with the guerrillas against imperial government. Although the harsh measure was not unprecedented in Mexican history even resembling an 1862 measure by Juárez,[30] it proved to be widely reviled, and contributed to the growing unpopularity of the Empire.[31]

In January 1866, seeing the war as unwinnable, Napoleon III declared to the French Chambers that he intended to withdraw the French military from Mexico. At this point, the U.S. government was no longer preoccupied militarily with winning the Civil War and could enforce the Monroe Doctrine against foreign intervention in the hemisphere. Maximilian's request to France for more aid or at least a delay in troop withdrawals was defused nominally because a possible war against Prussia was coming, so despite the sunk costs of the French occupation, abandoning the enterprise was France's strategic decision. Empress Carlota arrived in Europe in an attempt to plead for the Empire's cause, but she was unable to gain France's support.

Fall of Empire[edit]

As France withdrew its military, Maximilian's empire was headed toward collapse. In October 1866 Maximilian moved his cabinet from the capital to Orizaba, near the Gulf Coast port of Veracruz. He was widely rumored to be leaving Mexico. He contemplated abdication, and on 25 November held a council of his ministers to address the crisis faced by the Empire. They narrowly voted against abdication and Maximilian headed back towards the capital.[32] He intended to appeal to the nation in order to hold a national assembly which would then decide what form of government the Mexican nation was to take. Such a measure however would require a ceasefire from Juárez. The president of the republic would never consider an offer from the foreigner placed on the throne by Juárez's Mexican political enemies with the aid of a foreign power. Republican army troops on the ground were fighting to defeat those supporting the emperor.

After the hopeless national assembly project fell through, Maximilian focused on military operations. In February 1867, the last of the occupying French troops departed for France. Maximilian headed for the city of Querétaro, north of the capital, to join the bulk of his Mexican troops, numbering about 10,000 men. Republican generals Escobedo and Corona converged on Querétaro with 40,000 men. The city held out until being betrayed by an imperial officer who opened the gates to the liberals on 15 May 1867.[33]

Maximilian was captured and placed on trial with his leading generals Mejía and Miramón. All three were tried, sentenced to death and executed on 19 June 1867 by the republican army.

Government[edit]

A provisional statute was published in 1865, which laid the basic framework of the government. The emperor was to govern through nine ministries: of the Imperial Household, of State, of Foreign Relations, of War, of Government or Interior, of the Treasury, of Justice, of Public Instruction and Worship, and of Development. These ministries (except that of the Imperial Household) comprised the Council of Ministers, which discussed the affairs that the emperor referred to them. The emperor had the power to appoint the Minister of the Imperial Household and the Minister of State, and in turn, the Minister of State, which was ex officio the President of the Council of Ministers, was to appoint the rest of the Ministers.[34] A Council of State was given the power to frame bills and give advice to the emperor, and a separate private cabinet, serving as the emperor's liaison, was divided into civil and military affairs. Empress Carlota was given the right to serve as regent if under certain circumstances Maximilian was to be unavailable,[35] making her the first and woman to ever govern Mexico.[36][37][38] As a result of her appointment to regency, she is considered to be the first woman to rule in the Americas.[39]

Maximilian had many plans for Mexico, clearly not expecting his reign to be so short. In 1865, the imperial regime drew up plans to reorganize Mexican national territory and issued eight volumes of laws covering all aspects of government, including forest management, railroads, roads, canals, postal services, telegraphs, mining, and immigration.[40][41] The emperor passed legislation guaranteeing equality before the law and freedom of speech, and laws meant to defend the rights of laborers, especially indigenous workers. Maximilian attempted to pass a law guaranteeing the natives a living wage and outlawing corporal punishment for them, along with limiting their inheritance of debts. The measures faced backlash from the cabinet, but were ultimately passed during one of Carlota's regencies.[42] Labor laws in Yucatán actually became harsher on workers after the fall of the Empire.[43] A national system of free schools was also planned based on the German gymnasia and the emperor founded an Imperial Mexican Academy of Science and Literature.[44] Laws were published both in Spanish and in Nahuatl, the Aztec language, and Maximilian appointed leading Nahuatl scholar Faustino Galicia as an advisor to his government.[45]

The Empire placed an emphasis on Mexican history and culture, with Maximilian commissioning Mexican painters Rafael Flores, Santiago Rebull, Juan Urruchi, and Petronilo Monroy, to produce works depicting Mexican history, religious subjects, and portraits of Mexican rulers, including the imperial sovereigns themselves.[46] The prefects governing the provinces were instructed to protect archeological artifacts and Maximilian wrote to Europe asking the return of native artifacts that had been taken out of the country during the Spanish conquest, including articles that had belonged to Moctezuma II, and an Aztec codex.[47]

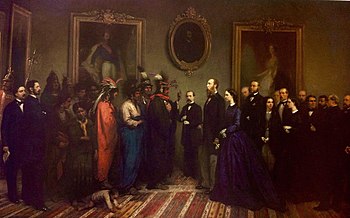

At Chapultepec Palace on Sundays, Maximilian and Carlota frequently held audiences with people from all social and economic segments, including Mexico's Indigenous Communities.[48] Maximilian aimed to promote the development of the country by opening up the nation to immigration, regardless of race. An immigration agency was set up to promote immigration from the United States, the former Confederate States, Europe, and Asia. Colonists were to be granted citizenship at once, and gained exemption from taxes for the first year, and an exemption from military services for five years.[49] Some of the most prominent colonization settlements were the Villa Carlota and the New Virginia Colony.[50]

Maximilian also established the Imperial Order of the Mexican Eagle as an award for extraordinary merits and services to the empire, for outstanding civil or military service, and outstanding achievements in the fields of science and art. It was considered the highest and most exclusive award during the Second Mexican Empire.

Economy[edit]

Railways[edit]

One of the main challenges encountered by the Emperor was the lack of sufficient infrastructure to link the different parts of the realm. The main goal was connecting the port of Veracruz and the capital in Mexico City. In 1857, Don Antonio Escandón secured the right to build a line from the port of Veracruz to Mexico City and on to the Pacific Ocean. Revolution and political instability stifled progress on the financing or construction of the line until 1864, when, under the regime of Emperor Maximilian, the Imperial Mexican Railway Company began construction of the line. Political upheaval continued to stifle progress, and the initial segment from Veracruz to Mexico City was inaugurated nine years later on 1 January 1873 by President Sebastián Lerdo de Tejada.[citation needed]

In 1857 the original proprietors of the government concession, the Masso Brothers, inaugurated on 4 July the train service from Tlatelolco, in México City, to the nearby town of Guadalupe Hidalgo.[51] Eventually they ran out of funds and decided to sell it to Manuel Escandón and Antonio Escandón.[52] The Escandón Brothers continued working and the project, and Antonio Escandón visited the United States and England in the last months of the year. In the first country, he hired Andrew Talcott, and in the latter, he sold company stock. Exploration of a route from Orizaba to Maltrata was performed by engineers Andrew H. Talcott and Pascual Almazán.[citation needed]

During the French intervention, part of the railways were destroyed. The only option available was the establishment of a pact between the French Army, and the two companies of the Escandón Brothers. The French Army was to provide a subsidy to the companies of 120 000 francs a month for the works, and the companies were to establish service from Veracruz to Soledad para by May, actually concluding on 15 August 1862, concluding 41 kilometres of tracks. Next they reached the Camarón station, with a length of 62 kilometres. By 16 October 1864 they reached Paso del Macho with a length of 76 kilometres.[53]

On 19 September 1864, the Imperial Mexican Railway Company (Compañía Limitada del Ferrocarril Imperial Mexicano) was Incorporated in London to complete the earlier projects and continued construction on this line. Escandón ceded his privileges to the new company. Smith, Knight and Co. was later contracted in 1864 by the Imperial Mexican Railway to continue work on the line from Mexico City to Veracruz.[54] William Elliot was employed as Chief Assistant for three years on the construction of about 70 miles of the heaviest portion of the Mexican Railway, after which he returned to England. He had several years of experience building railways in England, India, and Brazil. In this last country, he held the position of Engineer-in-Chief of the province of São Paulo.[55]

Maximiliano I hired engineer M Lyons for the construction of the line from La Soledad to Monte del Chiquihuite, later on joining the line from Veracruz to Paso del Macho.[56] Works were begun in Maltrata, at the same time that the works from Veracruz and Mexico City kept moving forward. By the end of the Empire in June 1867, 76 kilometers from Veracruz to Paso del Macho were functional (part of the concession to Lyons) and the line from Mexico City reached Apizaco with 139 km.[57][circular reference]

Banking[edit]

Before 1864, there was no system of banking in Mexico. Religious institutions were a source of credit for elites, usually for landed estates or urban property. During the French Intervention, the branch of a British bank was opened. The London Bank of Mexico and South America Ltd. began operations with a capital of two and a half million pesos. It belonged to the Baring Brothers Group, and had its head office in the corner of the Capuchinas and Lerdo Streets in Downtown Mexico City.[58]

Foreign trade[edit]

At the beginning of the American Civil War, the city of Matamoros was simply a sleepy little border town across the Rio Grande from Brownsville, Texas.[59] It had, for several years, been considered a port, but it had relatively few ships arriving. Previous to the war, accounts mention that not over six ships entered the port each year.[60] In about four years, Matamoros, due to its proximity to Texas, became an active port, and the number of inhabitants increased. A general of the Union Army in 1865 describes the importance of the port in Matamoros:

Matamoros is to the rebellion west of the Mississippi what New York is to the United States—its great commercial and financial center, feeding and clothing the rebellion, arming and equipping, furnishing it materials of war and a specie basis of circulation that has almost displaced Confederate paper...The entire Confederate Government is greatly sustained by resources from this port.[61]

The cotton trade brought together in Bagdad, Tamaulipas and Matamoros over 20,000 speculators from the Union and the Confederacy, England, France, and Germany.[62] Bagdad had grown from a small, seashore town to a "full-pledge town."[63] The English-speaking population in the area by 1864 was so great that Matamoros even had a newspaper printed in English—it was called the Matamoros Morning Call.[64] In addition, the port exported cotton to England and France, where millions of people needed it for their daily livelihood,[65] and it was possible to receive fifty cents per pound in gold for cotton, when it cost about three cents in the Confederacy, "and much more money was received for it laid down in New York and European ports."[66] Other sources mention that the port of Matamoros traded with London, Havana, Belize, and New Orleans.[67][68] The Matamoros and New York City trade agreement, however, continued throughout the war and until 1864, and it was considered "heavy and profitable."[69]

By 1865, Matamoros was described as a prosperous town of 30,000 people,[70] and Lew Wallace informed General Ulysses S. Grant that neither Baltimore or New Orleans could compare itself to the growing commercial activity of Matamoros.[60] Nevertheless, after the collapse of the Confederacy, "gloom, despondency, and despair" became evident in Matamoros—markets shut down, business almost ceased to exist, and ships were rarely seen.[71] "For Sale" signs began to sprout up everywhere, and Matamoros returned to its role of a sleepy little border town across the Rio Grande.[72]

The conclusion of the American Civil War brought a severe crisis to the now abandoned Port of Bagdad, a crisis that until this day the port has never recovered from.[73] In addition, a tremendous hurricane in 1889 destroyed the desolated port. This same hurricane was one of the many hurricanes during the period of devastating hurricanes of 1870 to 1889, which reduced the population of Matamoros to nearly half its size, mounting with it another upsetting economic downturn.[74][75]

Territorial division[edit]

Maximilian I wanted to reorganize the territory following scientific criteria, instead of following historical ties, traditional allegiances and the interests of local groups. The task of designing this new division was given to Manuel Orozco y Berra.

This task was realized according to the following criteria:

- The territory should be divided in at least fifty departments,

- Whenever possible, natural boundaries shall be preferred,

- For the territorial extension of each department, the configuration of the terrain, climate and elements of production were taken into consideration so that in due time, they could have a roughly equal number of inhabitants.[76]

On 13 March 1865, the new Law on the territorial division of the Mexican Empire was published.[77] The Empire was divided into 50 departments, though not every department was ever able to be administered due to the ongoing war.

Legacy[edit]

In spite of the Empire lasting only a few years, the results of Maximilian's construction projects survived him and remain prominent Mexico City landmarks in the present day.

For his royal residence, Maximilian decided to renovate a former viceregal villa in Mexico City, which was also notable for being the site of a battle during the U.S. invasion of Mexico. The result would be Chapultepec Castle, the only castle in North America ever to be used by actual royalty. After the fall of the empire, Chapultepec Castle served as the official resident of the Mexican president up until 1940, when it was converted into a museum.[78]

In order to connect the palace to the government offices in Mexico city, Maximilian also built a prominent road which he called Paseo de la Emperatriz (The Empress' Promenade). After the fall of the Empire, the government renamed it Paseo de la Reforma (Promenade of the Reform) to commemorate La Reforma. In the present, it continues to be one of the most prominent avenues of the capital and is lined with civic monuments.[79]

The bolillo, a type of bread widespread in Mexican cuisine, was brought to the country by Maximilian's cooks, and remains another legacy of the Imperial Era.[80]

Today, the Second Mexican Empire is advocated by small far-right groups like the Nationalist Front of Mexico, whose followers believe the Empire to have been a legitimate attempt to deliver Mexico from the hegemony of the United States. They are reported to gather every year at Querétaro, the place where Maximilian and his generals were executed.[81]

In popular culture[edit]

| History of Mexico |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

|

|

The 1970 film Two Mules for Sister Sara was set in Mexico during the years of the Second Mexican Empire. The two main characters, played by Clint Eastwood and Shirley MacLaine, aided a Mexican resistance force and ultimately led them to overpower a French garrison.

The 1969 film The Undefeated starring John Wayne and Rock Hudson portrays events during the French Intervention in Mexico and was also loosely based on the escape of Confederate General Sterling Price to Mexico after the American Civil War and his attempt to join with Maximilian's forces.

The 1965 film Major Dundee starring Charlton Heston and Richard Harris featured Union cavalry (supplemented by Galvanized Yankees) crossing into Mexico and fighting French forces towards the end of the American Civil War.

The 1954 film Vera Cruz was also set in Mexico and has an appearance of Maximilian having a target shooting competition with Gary Cooper and Burt Lancaster's character at Chapultepec Castle. Maximilian was played by George Macready, who at 54 was twenty years older than the Emperor was in 1866.

The 1939 film Juarez featured Paul Muni as Benito Juárez, Bette Davis as Empress Carlota, and Brian Aherne as Emperor Maximilian. It was based, in part, on Bertita Harding's novel The Phantom Crown (1937).

In the Southern Victory Series by Harry Turtledove, Maximilian's Empire survives the turmoil of the 1860s into the 20th century due to the Confederate States emerging victorious in its battle against the United States in the "War of Secession".

The 1990 novel The Difference Engine, co-authored by William Gibson and Bruce Stirling, is set in an alternate 1855 where the timeline diverged in 1824 with Charles Babbage's completion of the difference engine. One consequence is the occupation of Mexico by the Second French Empire with Napoleon III as the de facto emperor instead of the installation of Emperor Maximilian.

In Mexican popular culture, there have been soap operas like "El Carruaje" (1967), plays, films, and historical novels such as Fernando del Paso's Noticias del Imperio (1987). Biographies, memoirs, and novels have been published since the 1860s, and among the most recent have been Prince Michael of Greece's The Empress of Farewells, available in various languages.

See also[edit]

- First Mexican Empire

- Second French intervention in Mexico

- Imperial Crown of Mexico

- Emperor of Mexico

- Mexican Imperial Orders

- Nationalist Front of Mexico

- Cabinet of Maximilian I of Mexico

References[edit]

- ^ a b Kirkpatrick, F.A., Latin America: A brief history (2013), Cambridge University Press, p. 339.

- ^ Duncan, Robert H., Rodriguez, Jaime E., The Divine Charter Constitutionalism and Liberalism in Nineteenth-Century Mexico, Rowman and Littlefield Publishers. pp. 134–138

- ^ Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1887). History of Mexico Volume VI 1861–1887. San Francisco: The History Company. p. 136.

- ^ Covarruvias José, Enciclopedia Política de México, Tpmp IV, Edit. Belisario Domínguez. 2010

- ^ Guedalla, Philip (1923). The Second Empire. Hodder and Stoughton. p. 322.

- ^ Duncan, Robert H., Rodriguez, Jaime E., The Divine Charter Constitutionalism and Liberalism in Nineteenth-Century Mexico, Rowman and Littlefield Publishers. pp. 134–138

- ^ Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1887). History of Mexico Volume VI 1861–1887. San Francisco: The History Company. pp. 136.

- ^ Miquel de la Rosa (2022). French Liberalism and Imperialism in the Age of Napoleon III. Springer Nature. p. 3. ISBN 978-3030958886.

- ^ Roger D. Price (2002). Napoleon III and the Second Empire. Routledge. ISBN 978-1134734689.

- ^ Hamnett, Brian R. A Concise History of Mexico (3rd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 2019, 222.

- ^ Eric Van Young, Stormy Passage: Mexico from Colony to Republic, 1750–1850. Lanham MD: Rowman and Littlefield 2022, 181, 183

- ^ de Zavala, Lorenzo (1832). Ensayo Histórico de las Revoluciones de Mégico: Desde 1808 Hasta 1830. New York: Elliott and Palmer. p. 248.

- ^ Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1852). History of Mexico Vol 5. The Bancroft Company. pp. 224–225.

- ^ Shawcross, Edward (2018). France, Mexico and Informal Empire in Latin America. Springer International. pp. 105–106. ISBN 978-3319704647.

- ^ Manuel Hidalgo y Esnaurrízar, José (1864). Apuntes para escribir la historia de los proyectos de monarquía en México (in Spanish). pp. 26–27.

- ^ Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1887). History of Mexico Volume VI 1861–1887. San Francisco: The History Company. p. 51.

- ^ Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1887). History of Mexico Volume VI 1861–1887. San Francisco: The History Company. pp. 77–78.

- ^ Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1887). History of Mexico Volume VI 1861–1887. San Francisco: The History Company. pp. 136.

- ^ Butler, John Wesley (1918). History of the Methodist Episcopal Church in Mexico. University of Texas.

- ^ Campbell, Reau (1907). Campbell's New Revised Complete Guide and Descriptive Book of Mexico. Rogers & Smith Company. p. 38 .

- ^ Putman, William Lowell (2001) Arctic Superstars. Light Technology Publishing, LLC. p. xvii

- ^ Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1888). History of Mexico Volume VI 1861–1887. The Bancroft Company. p. 150.

- ^ Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1888). History of Mexico Volume VI 1861–1887. The Bancroft Company. p. 152.

- ^ Shawcross, The Last Emperor of Mexico, 141–44

- ^ Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1888). History of Mexico Volume VI 1861–1887. The Bancroft Company. pp. 154–155.

- ^ Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1888). History of Mexico Volume VI 1861–1887. The Bancroft Company. p. 181.

- ^ Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1888). History of Mexico Volume VI 1861–1887. The Bancroft Company. pp. 206–207.

- ^ Wooster, Robert (2006). "John M. Schofield and the 'Multipurpose' Army". American Nineteenth Century History. 7 (2): 173–191. doi:10.1080/14664650600809305. S2CID 143091703.

- ^ Richter, William (2012). Historical Dictionary of the Civil War and Reconstruction. The Bancroft Company. p. 429.

- ^ Mayer, Brantz (1906). México, Central America and West Indies. John D. Morris and Company. p. 391.

- ^ Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1888). History of Mexico Volume VI 1861–1887. The Bancroft Company. pp. 183–184.

- ^ Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1888). History of Mexico Volume VI 1861–1887. The Bancroft Company. p. 241.

- ^ Fehrenbach, T.R. (1995). Fire and Blood: A History of Mexico. Da Capo Press. p. 438. ISBN 978-0306806285.

- ^ de Habsburgo, Maximiliano. "Estatuto Provisional del Imperio Mexicano" (PDF). Orden Jurídico. Gobierno de México. Retrieved 12 January 2023.

- ^ Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1887). History of Mexico Volume VI 1861–1887. San Francisco: The History Company. p. 171.

- ^ Triedo, Nicolás (12 July 2018). "Carlota: la emperatriz de México". Mexico Desconocido (in Spanish).

- ^ "Ella es la primera mujer que gobernó en México, pero no tuvo un final feliz". El Sol de Hermosillo (in Spanish). 24 January 2022.

- ^ Brooks, Darío. "Carlota de México: quién fue la emperatriz y primera gobernante del país (y qué legado dejó)". BBC News Mundo (in Spanish).

- ^ "Carlota, The Belgian Princess Who Went Mad When She Became A Mexican Empress". Cultura Colectiva. Retrieved 2 October 2022.

- ^ La legislación del Segundo Imperio (PDF) (in Spanish). p. 9.

- ^ McAllen, M.M (2014). Maximilian and Carlota: Europe's Last Empire in Mexico. Trinity University Press. p. 143. ISBN 978-1595341853.

- ^ McAllen, M.M (2014). Maximilian and Carlota: Europe's Last Empire in Mexico. Trinity University Press. p. 182. ISBN 978-1595341853.

- ^ Richmond, Douglas W. (2015). Conflict and Carnage in Yucatán: Liberals, the Second Empire, and Maya Revolutionaries, 1855–1876. University of Alabama Press. p. 70. ISBN 978-0817318703.

- ^ Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1887). History of Mexico Volume VI 1861–1887. San Francisco: The History Company. p. 173.

- ^ McAllen, M.M. (2014). Maximilian and Carlota: Europe's Last Empire in Mexico. Trinity University Press. p. 142. ISBN 978-1595341853.

- ^ McAllen, M.M. (2014). Maximilian and Carlota: Europe's Last Empire in Mexico. Trinity University Press. p. 166. ISBN 978-1595341853.

- ^ McAllen, M.M. (2014). Maximilian and Carlota: Europe's Last Empire in Mexico. Trinity University Press. p. 167. ISBN 978-1595341853.

- ^ McAllen, M.M (2014). Maximilian and Carlota: Europe's Last Empire in Mexico. Trinity University Press. p. 169. ISBN 978-1595341853.

- ^ Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1887). History of Mexico Volume VI 1861–1887. San Francisco: The History Company. p. 174.

- ^ Wahlstrom, Todd W. The Southern Exodus to Mexico: Migration Across the Borderlands after the American Civil War. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press 2015.

- ^ Ferrocarril de México a La Villa

- ^ La historia del tren en México

- ^ Chapman, John Gresham, La construcción del Ferrocarril Mexicano, 1985

- ^ The Railroads of Mexico

- ^ William Elliot (1827–1892) Grace's Guide to British Industrial History

- ^ Historia del Ferrocarril

- ^ es:Ferrosur

- ^ Banco de Londres, México y Sudamérica, el primer banco comercial de México Forbes

- ^ Delaney, Robert W. (1955). "Matamoros, Port for Texas during the Civil War". The Southwestern Historical Quarterly. Texas State Historical Association. 58 (4): 487. ISSN 0038-478X. JSTOR 30241907.

- ^ a b The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Washington: United States. War Dept. 1880–1901. JSTOR 30241907.

- ^ Underwood, Rodman L. (2008). Waters of Discord: The Union Blockade of Texas During the Civil War. McFarland. p. 200. ISBN 978-0786437764.

- ^ "Matamoros". New Orleans Times. 1 June 1865. JSTOR 30241907.

- ^ "New York Herald". 9 January 1865. JSTOR 30241907.

- ^ "The Southwestern Historical Quarterly". New Orleans Daily True Delta. 16 December 1864.

- ^ Official Records of the War of the Rebellion. Washington: United States Department of War. 1894–1922. JSTOR 30241907.

- ^ Henry, Robert S. (1989). The State of the Confederacy. New York: Da Capo Paperback. p. 342. JSTOR 30241907.

- ^ "Matamoros and Belize: "From powder and caps to a needle"". New Orleans Times. 12 November 1864. JSTOR 30241907.

- ^ Hanna, Alfred J. (May 1947). "The Immigration Movement of the Intervention and Empire as Seen Through the Mexican Press". The Hispanic American Historical Review. Duke University. 27 (2): 246. doi:10.1215/00182168-27.2.220. JSTOR 2508417.

- ^ "Matamoros and New York: Heavy and profitable". New Orleans Era. 1 November 1864. JSTOR 30241907.

- ^ "Matamoros port: 30,000 inhabitants". New Orleans Times. 3 March 1865. JSTOR 30241907.

- ^ "Port of Matamoros: "gloom, despondency, and despair"". New York Herald. 17 March 1865.

- ^ "Port of Matamoros". New Orleans Times. 1 June 1865. JSTOR 30241907.

- ^ Buenger, Walter L. (November 1984). "Reviewed work: The Matamoros Trade: Confederate Commerce, Diplomacy, and Intrigue., James W. Daddysman". The Journal of Southern History. Southern Historical Association. 50 (4): 655–656. doi:10.2307/2208496. ISSN 0022-4642. JSTOR 2208496.

- ^ Schober, Otto. "Cuando el río Bravo era navegable". Zócalo Saltillo.

- ^ Beezley, William H. (2011). A Companion to Mexican History and Culture. John Wiley & Sons. p. 688. ISBN 978-1444340570.

- ^ Rubén García, "Biografía, bibliografía e iconografía de don Manuel Orozco y Berra", en Boletín de la Sociedad Mexicana de Geografía y Estadística, México, Compañía Editora e Impresora "La Afición", 1934, p. 233.

- ^ Diario del Imperio, Tomo I Número 59, 13 de marzo de 1865

- ^ "Chapultepec Castle: The only castle in North America to ever house actual sovereigns".

- ^ "Paseo de la Reforma in Mexico City". 25 June 2022.

- ^ "Historia del origen del bolillo". 5 November 2019.

- ^ "Homage to the Martyrs of the Second Mexican Empire". Archived from the original on 3 May 2014.

Further reading[edit]

- Anderson, William Marshall. An American in Maximilian's Mexico, 1865–1866: Diaries of William Marshall Anderson. Edited by Ramón Eduardo Ruiz. San Marino CA: Huntington Library 1959.

- Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1887). History of Mexico Volume VI 1861–1887. San Francisco: The History Company. pp. 171–173.

- Barker, Nancy N. "The Factor of 'Race' in the French Experience in Mexico, 1821–1861", in: HAHR, no. 59:1, pp. 64–80.

- Barker, Nancy Nichols. The French Experience in Mexico, 1821–1861: A History of Constant Misunderstanding. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press 1979.

- Blumberg, Arnold. "The diplomacy of the Mexican empire, 1863–1867." Transactions of the American Philosophical Society 61.8 (1971): 1–152.

- Blumbeg. Arnold: The Diplomacy of the Mexican Empire, 1863–1867. Florida: Krueger, 1987.

- Corti, Egon Caesar: Maximilian and Charlotte of Mexico, translated from the German by Catherine Alison Phillips. 2 Volumes. New York: Knopf, 1928.

- Cunningham, Michele. Mexico and the Foreign Policy of Napoleon III (2001) 251 pp. online PhD version, University of Adelaide 1996

- Duncan, Robert H. "Political Legitimation and Maximilian's Second Empire in Mexico, 1864–1867." Mexican Studies/Estudios Mexicanos (1996): 27–66.

- Duncan, Robert H. "Embracing a Suitable Past: Independence Celebrations under Mexico's Second Empire, 1864–6." Journal of Latin American Studies 30.2 (1998): 249–277.

- Pani, Erika: "Dreaming of a Mexican Empire: The Political Projects of the 'Imperialist'", in: Hispanic American Historical Review, no. 65:1, pp. 19–49.

- Hanna, Alfred Jackson, and Kathryn Abbey Hanna. Napoleon III and Mexico: American triumph over monarchy (1971).

- Ibsen, Kristine (2010). Maximilian, Mexico, and the Invention of Empire. Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press. ISBN 978-0826516886.

- McAllen, M. M. (2015). Maximilian and Carlota: Europe's Last Empire in Mexico. San Antonio: Trinity University Press. ISBN 978-1595341839. excerpt

- Ridley, Jasper (2001). Maximilian & Juarez. London: Phoenix Press. ISBN 1842121502.

External links[edit]

![]() Media related to Second Mexican Empire at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Second Mexican Empire at Wikimedia Commons

- Mexican Empire

- Independent Mexico

- Second French intervention in Mexico

- Maximilian I of Mexico

- Mexican monarchy

- Former monarchies

- Former unrecognized countries

- 1860s in Mexico

- History of Mexico

- Christian states

- Political history of Mexico

- 19th-century colonization of the Americas

- States and territories established in 1863

- States and territories disestablished in 1867

- 1863 establishments in Mexico

- 1867 disestablishments in Mexico

- French colonization of the Americas

- French colonial empire

- House of Habsburg-Lorraine

- Titles of nobility in the Americas

.svg/125px-Flag_of_the_Second_Mexican_Empire_(Imperial_Banner).svg.png)

.svg/280px-Political_divisions_of_Mexico_1865_(location_map_scheme).svg.png)

.JPG/300px-Castillo_de_Chapultepec_(Museo_Nacional_de_Historia).JPG)