November 19th, 2009 § § permalink

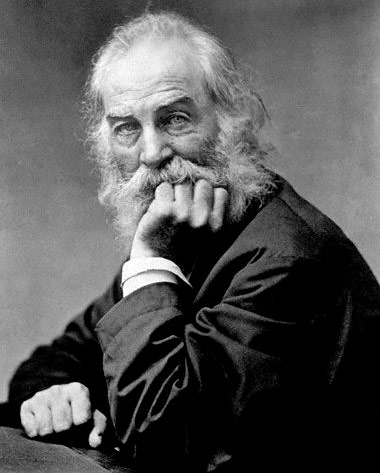

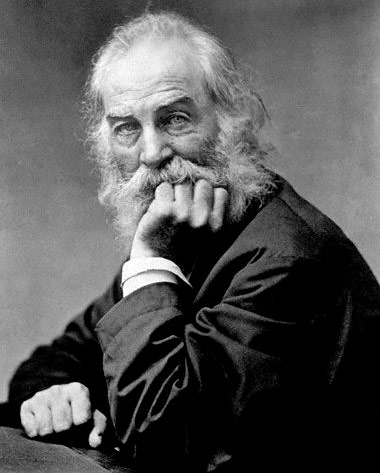

The last two weeks of class discussion have made me think long and hard about the changing nature of Whitman’s poetry in his later years. The famous poems that are highlighted in poetry courses include a broad selection of his early works, but very few seem to mention his later verse. I had no idea about Whitman’s years in Camden until I came to this university. And while his late poetry does not have the martial rhyme or political punch of his early writing, the quiet contemplation and appreciation of nature and life is touching.

If Whitman ever had fears about dying, it does not show in his poetry. Even with his debilitating ailments, he only writes about the appreciation of life, never about his struggles with sickness or the fight from day to day. The diminishment of energy is evident in these later works; many of his poems consist only of a few lines, where earlier Whitman could have expanded them into grand poems with scores of lines.

The metaphors that Whitman uses are also far more commonplace. Old age is the night of a long day, or the winter of the seasons of life. His poetry, once full of direct detail and on-the-scene footage now resorts to imagery, metaphor and symbolism in order to catch its effect. It is no surprise that Whitman has turned introspective–the forces he is dealing with now, most of all death, are intangible and largely unknown.

November 10th, 2009 § § permalink

Whitman’s writing from Sands and Seventy centers itself on reflections on the past as well as meditations on the nature of death. The poems in this selection are far shorter than the grand verse of Whitman’s youth, not to mention the first publication of his grand epic Leaves of Grass. The tone is markedly humble, but little hints and flashes of the strong rhetoric of his Drum-Taps days appear here and there throughout his poetry.

“Election Day, November, 1884” is one of these. Whitman praises America’s democratic process, a force that excels even the greatest natural wonders of the nation. This election is termed “a swordless conflict,” even though the face-off between Grover Cleaveland (D) and James G. Blaine (R) was known for vicious mudslinging and personal attacks on morals and integrity. As we all know from history, Grover Cleaveland won the election, becoming the first democratic president elected since before the Civil War. While learning about the presidents as a child, I could never forget that Cleaveland was the only president to serve two non-consecutive terms in office: 1885-9 and 1893-7.

Whitman also offers up a common poetic metaphor for his thoughts on death. The Sea has always been a popular source of poetic symbolism, representing many things, including birth and rebirth, death, and mysterious femininity. Whitman draws on the masculine strength of death as a source of poetic inspiration itself, imagining that the waves have their own voices: “many a muffled confession–many a sub and whisper’d word,/As of speakers far or hid” (Fancies at Navesink, 27-8).

These wave-poets also suffer from debilitating old age, just as the many poets of ancient times: “Poets unnamed–artists greatest of any, with cheris’d lost designs,/Love’s unresponse–a chorus of age’s complaints–hope’s last words,/Some suicide’s despairing cry, Away to the boundless waste, and never again return” (30-33). Whitman embraces the idea of oblivion of death, avoiding typical flowery language and purple prose associated with passing.

Whitman’s poetry is subdued, yet not defeatist. While the poet may be unsure about his legacy, he shows no fear in the face of death in his poetry, but rather looks forward to nature’s cleansing of the debilitating pains of old age. The memories of his past are precious to his time in old age, and his reflections are just as essential to his poetry and prose as are his war poems and nationalistic verse.

November 5th, 2009 § § permalink

Songs of Parting and Whitman’s poetry from later years is particularly poignant in its acceptance of the oncoming specter of death. It seems that the atrocities of the Civil War made the poet all too familiar with scenes of passing, and his poetry is calm and accepting of death’s shadow. Whitman is sure of his survival through his works of poetry and prose, but the mentions of his fading health are touching and deeply saddening.

I shall go forth,

I shall traverse the States awhile, but I cannot tell wither or how long,

Perhaps soon some day or night while I am singing my voice will suddenly cease.

(As the Time Draws Nigh, 3-5)

Whitman realizes that he soon may not be able to continue writing poetry, that his weak health may prevent him from continuing his work as America’s poet. But he continues to press on, looking ahead to the future of an America that wholly embraces equality. Whitman looks forward to an America that realizes the civil rights of citizens of all races. He stands against the divisions of caste and the classical hierarchy of European monarchical rule. Through technology, such as the steamship, the telegraph and the newspaper, Whitman looks forward to a global, integrated world, much like our modern world today.

It is interesting to think of Whitman’s embrace of technology and the great push in advancements that have happened in the last twenty years, not to mention the last century. Today’s world is dependent on global communication, trade and business, and political negotiation. We cook international foods in our own kitchens, we instantly chat with men and women from around the globe. The internet is a force that spreads democracies in autocratic nations in a way that war and troops never could. Our cultural borders are constantly expanding and while the world grows smaller, our own lives grow richer because of it.

It is hard to imagine what poetry Whitman would pen in response to this globalization, but I am sure that he would be in the forefront of it all, bringing us into awareness of the changes in America occurring around us.

Would Whitman be one of the men walking down the streets of Philadelphia with his blackberry? Even so, I am sure he would be among the few of us to put his phone away to take a real look around.

October 20th, 2009 § § permalink

The Tomb of Walt Whitman

Walt Whitman’s final resting place is located in Harleigh Cemetery in Camden, New Jersey. The cemetery opened in 1885, only seven years before Whitman’s death, making it one of the oldest cemeteries in New Jersey. The cemetery covers over 130 acres of land, full of trees, sloping hills and gardens (Wikipedia).

In 1890, Whitman began making preparations for the spot of his burial, signing a contract for $4000 for the construction of a “burial house” in the cemetery, sturdy and geometric, carved roughly of granite with his name emblazoned on the front stone face. But what moved Whitman, usually the model of frugality, to decide on such an expensive burial structure?

Although Whitman grew up in poverty, by the last fifteen years of his life in Camden his salary averaged $1200 a year, a third more than the standard salary of an American worker (Reynolds, p. 32). By that standard, the cost of the tomb was over three times his annual salary. But Whitman cleverly relied on his good connections to pull him through the transaction–after paying the first $1500, he refused to pay for the last installment, relying on a rich friend to pick up the rest of the tab. Yet Whitman was quite liberal with the rest of his estate and possessions, giving liberally to his family members, five of which occupy the tomb along with him.

Young Harleigh Cemetery

One question that arises regards Whitman’s choice of such a young graveyard in which to build his tomb. Practical concerns such as space for the large stone structure were certainly concerns, and Whitman undeniably had the choicest pickings of the site for his location. But there seems to be evidence that Whitman may have been given a good deal by Harleigh Cemetery. According to one source, the cemetery convinced Whitman to pick a plot in order to increase business. By burying Whitman, a famous poet as well as a Camden local, Harleigh Cemetery rose in value and in business dramatically (Tomb of Walt Whitman Camden NJ).

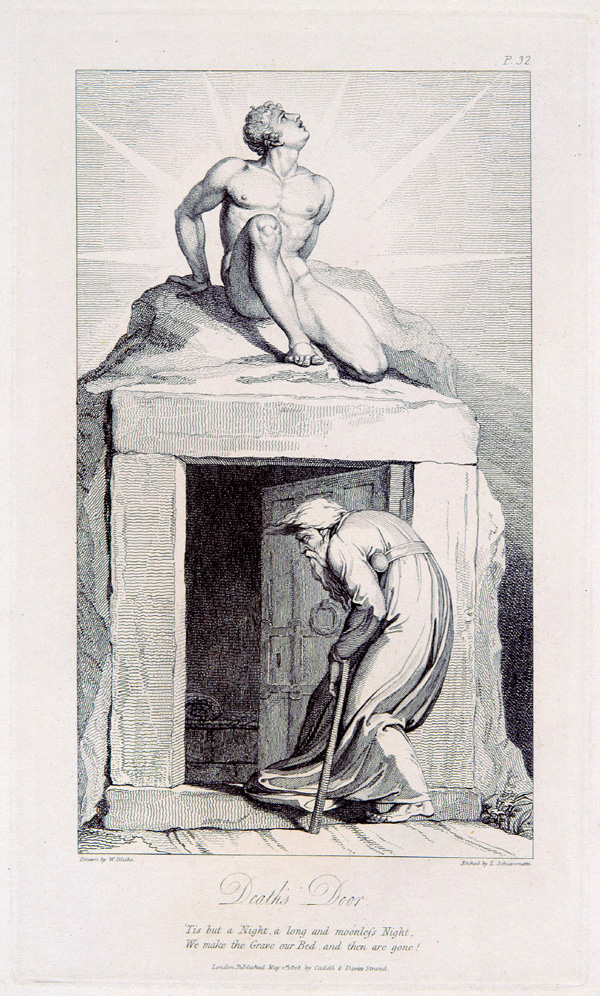

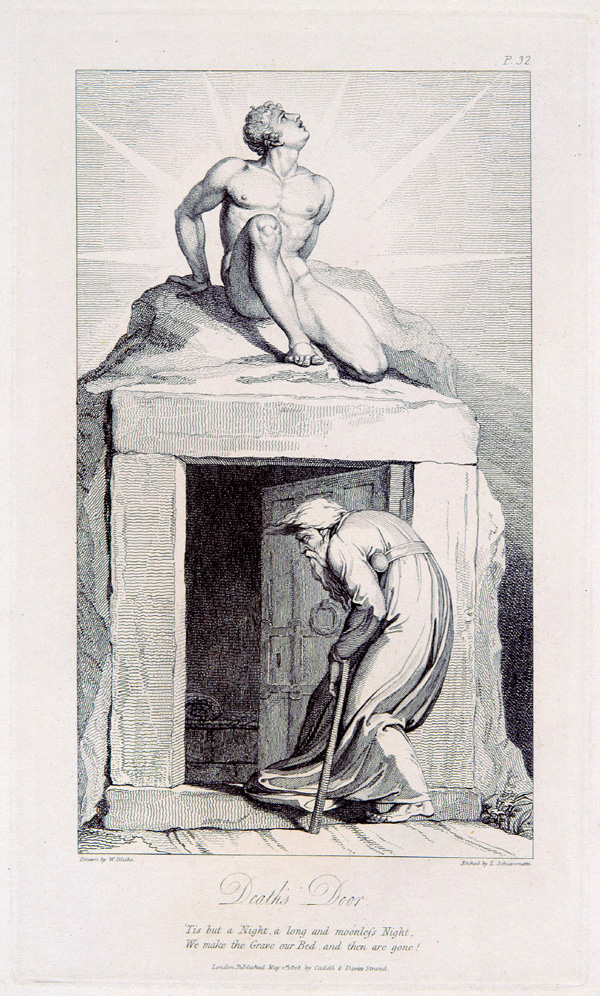

Blake’s “Death’s Door”

The model for Whitman’s tomb is based on William Blake’s engraving, “Death’s Door” which Whitman discovered in 1881 (Ferguson-Wagstaffe). Whitman submitted a sketch to his literary executor, with the comment, “Walt Whitman’s Burial Vault–on a sloping wooded hill–grey granite–unornamental–surrounding trees, turf, sky, a hill everything crude and natural.” Whitman’s concept of a tomb was one carved out of nature, part of the earth yet separate from it. It is clear that Whitman intended to make a statement, but he disliked the grand, European style of mausoleums. The result is of Whitman’s desires was a tomb built to be earthen and sturdy, rather than polished and refined.

Burial Rituals

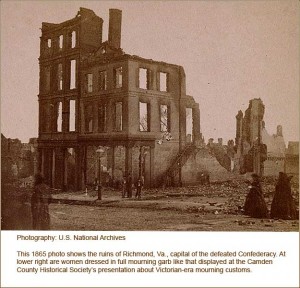

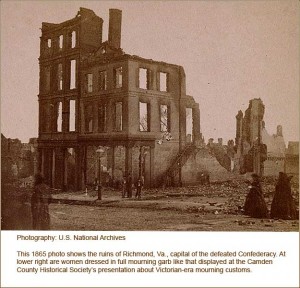

Rituals regarding burial began to change in the nineteenth century, leading to new practices and a new design of graveyard. The Civil War was one of the catalysts, quickly robbing many households of fathers and sons–totaling up to approximately 600,000 casualties (Historic Camden County). Isolated burial grounds soon gave way to cemeteries that took the form of pubic parks. Victorian garden landscapes became the standard, where relatives would come to pray for, and picnic with, the deceased. Harleigh Cemetery represents one of these, founded after the civil war. Whitman’s request for a tomb was not unusual during this period of public graveyard revival.

Rituals regarding burial began to change in the nineteenth century, leading to new practices and a new design of graveyard. The Civil War was one of the catalysts, quickly robbing many households of fathers and sons–totaling up to approximately 600,000 casualties (Historic Camden County). Isolated burial grounds soon gave way to cemeteries that took the form of pubic parks. Victorian garden landscapes became the standard, where relatives would come to pray for, and picnic with, the deceased. Harleigh Cemetery represents one of these, founded after the civil war. Whitman’s request for a tomb was not unusual during this period of public graveyard revival.

Today Whitman’s tomb remains a site for the public, both of his literary fans and of roaming tourists. The tomb remains unchanged on a grassy hillside in Harleigh cemetery, open to visitors.

In Autumn Rivulets, Whitman’s Outlines for a Tomb ends with a passage of the narrator transcending the borders of America and beyond.

O thou within this tomb,

From thee such scenes, thou stintless, lavish giver,

Tallying the gifts of earth, large as the earth,

Thy name an earth, with mountains, fields and tides.

Nor by your streams alone, you rivers,

By you, your banks Connecticut,

By you and all your teeming life, old Thames,

By you Potomac laving the ground Washington trod, by you Patapsco,

You Hudson, you endless Mississippi–nor you alone,

But to the high seas launch, my thought, his memory.”

Instead of being weighed down by death, the narrator transcends borders with his thoughts. In this way, Whitman transcends his own death, not only through the erection of his tomb, but through the survival of his poetry and prose and those who study and learn by his works.

Works Cited

Fergusun-Wagstaffe, Sarah. “‘Points of Contact’: Blake and Whitman–Sullen Fires Across the Atlantic: Essays in Transatlantic Romanticism.” Harvard University. Romantic Circles. University of Maryland.

“Harleigh Cemetery, Camden.” <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harleigh_Cemetery,_Camden> Wikipedia.

Levins, Hoag. “Civil War-Era Death and Mourning Customs and Rituals” HistoricCamdenCounty.com. October 28th, 2002. <http://historiccamdencounty.com/ccnews43.shtml>

Reynolds, David S. Walt Whitman: Benjamin Franklin’s Representative Man. Modern Language Studies, Vol. 28, No. 2 (Spring, 1998), p. 29-39.

“Tomb of Walt Whitman, Camden NJ, American Guide Series on Waymarking.com” Waymarking.com. <http://www.waymarking.com/waymarks/WM70J8_Tomb_of_Walt_Whitman_Camden_NJ>

October 20th, 2009 § § permalink

All of us are familiar with Whitman’s fascination with physiognomy, the assessment of a person’s character by their outward appearance. From what I’ve heard, he had his own head read on several occasions.

It makes sense, then, that Whitman donated his own brain to science upon his death. His brain was kept preserved at the Wistar Institute at the University of Pennsylvania, as part of a collection of other brains from intelligent and renowned figures.

Unfortunately, at some point in time Whitman’s brain was dropped by a lab assistant–and therefore ruined and discarded.

Poor Whit–he must have turned over in his grave.

For the curious, here is the article where I found this.

October 20th, 2009 § § permalink

“For want of anything better, let me lightly twine a spring of the sweet ground-ivy trailing so plentifully through the dead leaves at my feet…and lay it as my contribution on the dead bard’s grave” (941).

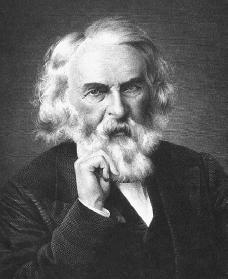

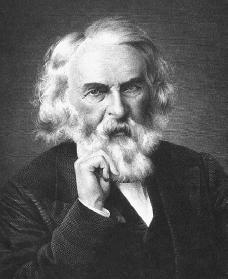

Although they were contemporaries, the writing of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and Walt Whitman could not be more different. Longfellow was by far the era’s most popular poet, a “fireside poet” whose poems for adults and children were popular with the masses. Whitman, the rabble rouser, wrote poetry for the masses, but was not quite as popular as Longfellow with the common man. Perhaps Longfellow’s charming rhymes, gentle cadence and mild, uncontroversial subject matter was better suited as recreation for the layman’s lifestyle. Whitman was beloved by his fans, attracting notice by British readers for his revolutionary work.

Although they were contemporaries, the writing of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and Walt Whitman could not be more different. Longfellow was by far the era’s most popular poet, a “fireside poet” whose poems for adults and children were popular with the masses. Whitman, the rabble rouser, wrote poetry for the masses, but was not quite as popular as Longfellow with the common man. Perhaps Longfellow’s charming rhymes, gentle cadence and mild, uncontroversial subject matter was better suited as recreation for the layman’s lifestyle. Whitman was beloved by his fans, attracting notice by British readers for his revolutionary work.

In Specimen Days on April 3rd, 1882, Whitman learns about the death of Longfellow through the newspaper and reminisces on the accomplishments of the fellow poet. His comments seem to weigh disapproval with plentiful praise, beginning with, “Longfellow in his voluminous works seems to me not only to be eminent in the style and forms of poetical expression that mark the present age, (an idiosyncrasy, almost a sickness, of verbal melody,) but to bring what is always dearest as poetry to the general human heart and taste” (941.) Whitman is not a fan of Longfellow’s insistent use of rhyme, the usage of which is not mere style, but a sickness, a dependance on formal verse. Poetry that reads like a song is suited to the common man’s taste, but this appears to be a degradation rather than an enhancement of the form. Longfellow adapts poetry to be readable by a large audience, simplifying it and its art for the general populace.

Yet Whitman goes on to claim that Longfellow represents “the sort of bard and counteractant most needed for our materialistic, self-assertive, money-worshipping Ango-Saxon races, and especially for the present age in America–an age tyrannically regulated with reference to the manufacturer, the merchant, the financier, the politician and the day workman–for whom and among whom he comes as the poet of melody, courtesy, deference” (942). Longfellow is the one poet to take the gift of poetry beyond the literary minded and share its music and its power with the everyday workman. In this way, Longfellow democracizes poetry, making it accessible to all those who are able to read. Poetry now has its place beside storytelling and biblical texts as one of America’s most popular literary pastimes.

Longfellow is the “universal poet of women and young people”–a poet of sentimentality (942). Whitman defends Longfellow from his critics who claim that the poet’s lack of originality. Originality is dependent on the exploration and study of the literary figures and works of the past. Before America, the New World, “can be worthily original, and announce herself and her own heroes, she must be well saturated with the originality of others, and respectfully consider the heroes that lived before Agamemnon” (943).

October 13th, 2009 § § permalink

Everyone has heard of the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier in the Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia. Just as the monument honors the nameless and unrecovered soldiers of our country’s wars, Whitman also sets his pen to do justice to the unburied and forgotten brave heroes of the civil war:

No formal general’s report, nor book in the library, nor column in the paper, embalms the bravest, north or south, east or west. Unnamed, unknown, remain, and still remain, the bravest soldiers. (Whitman, p. 748.)

Unnamed Remains the Bravest Soldier is one passage of many that celebrate the strength of America’s fighting youth, both on the field and in the hospitals. Whitman gives name to these men, abbreviating some to protect their privacy, but details their bravery in the face of pain and death, their strong silence and humbleness and their struggle and will to survive. Each case or “specimen” in Whitman’s work gives a unique and individual clause to the greater work, bringing the account of the war down to a personal, humanitarian level.

Whitman spoke in the preface to Leaves of Grass that America was itself one great poem, and that a poet of the people must write from the level of the common man. Therefore, Whitman does not wax patriotic with stories of the heroism of the generals of the war, but details the ins and outs of the cavalry and infantry. Even his passages about Lincoln describe the president as humble, courteous and yet deep and distinguished in the sadness in his face. Lincoln and his wife go about attired in black in a simple carriage, and while the president is alone he goes with a small ensemble of cavalry at the insistence of this men.

The hot-blooded patriotism of Whitman’s early poems is absent here, replaced with gruesome scenes of the hospital and the field. Whitman describes a battlefield in a fiery wood in A Night Battle, Over a Week Since. Both the wounded and the dead are consumed in the fire, flames that echo the burns that soldiers sustain if they survive the enemy cannon fire. Other scenes describing amputation, gangrene and violent hemorrhages range from stirring to deeply disturbing. Most of the soldiers are young, often between ages sixteen and twenty-one, and often described as farm boys–those who have little stake in the struggle between plantation owners and northern factory workers.

In Europe’s many military conflicts it came as no surprise that wars were waged by the rich with the ranks of the poor. America may claim to be different, but the reality of the Civil War proves that even democracy does not prevent this bitter, cruel reality from occurring.

October 6th, 2009 § § permalink

Each time I read Whitman’s verse on Lincoln it never fails to inspire me.

Lincoln's funeral train

Lincoln was the first president whose funeral was taken to the public on a grand scale–his coffin was set on a thirteen day journey by train. The train and its attendees traveled from Washington to Springfield, Illinois, through seven states and several major cities. Hundreds of thousands of people attended the viewing of the president in Philadelphia alone.

According to accounts “Long lines of the general public began forming by 5:00 A.M. At its greatest, the double line was three miles long and wound from the Delaware to the Schuylkill. Philadelphia officials estimated 300,000 people passed by Mr. Lincoln’s open coffin. The wait was up to five hours. So many people wanted to view Mr. Lincoln’s body that police had difficulty maintaining order in the lines; some people had their clothing ripped, others fainted, one broke her arm.”

Lincoln’s death was universally mourned, and Whitman’s elegy for the president is emotionally stirring, evoking both the poet as a lone mourner as well as the throngs that flocked to behold the president in death. Whitman describes the journey of the coffin through the rural landscapes of America as it travels from east to west. But the poem does not linger on the journey itself, but also grasps a greater effect by detailing Lincoln’s “burial house”–the symbols that represent the great man:

Pictures of growing spring and farms and homes,

With the Fourth-month eve at sundown, and the gray smoke lucid and bright,

With floods of the yellow gold and gorgeous, indolent, sinking sun, burning, expanding the air,

With the fresh sweet herbage under foot, and the pale green leaves of the trees prolific…

And the city at hand with dwellings so dense, ands tacks of chimneys,

And all the scenes of life and the workshops, and the workmen homeward returning (462.)

Whitman immortalizes Lincoln as the morning star, the star that sets in the west with his death. The narrator is then held between the thrush’s poetic exuberance on death and the mournful pull of memory of Lincoln in life. Death is celebrated as a companion, a universal force worthy of praise, an escape from the suffering of living. Yet the narrator moves between these two forces throughout the entire poem, only to escape the cycle and move beyond the lilac and the star at its very conclusion. The poem ends with praise for “the sweetest, wisest soul of all my days and lands” and the release of Lincoln into the embrace of death and his immortalization through the ode.

September 29th, 2009 § § permalink

Is it fair to write Whitman off as merely bawdy?

If the highly explicit passages from Children of Adam and Calamus are noted, Whitman pulls no stops on shocking and exciting his readers with his revelations of the passion of lovers. But Whitman makes an explicit reference to a higher purpose in From Pent-up Aching Rivers–not only does he sing the praises of the body, but he aims at a higher social purpose.

In the very beginning of the poem, Whitman states that sex is so consuming and essential to him that he will stand against social impropriety to proclaim it: “From what I am determin’d to make illustrious, even if I stand sole among men/From my own voice resonant, singing the phallus” (p. 248-9.) The passion defines his identity, “from that if myself without which I were nothing” (248.) The joyful union of two lovers is one of the greatest compelling forces behind Whitman’s verse that it is difficult to imagine what his poetry would look like without its drive.

The passage is full of a constantly changing dynamic of yield and command, possession and submission. The master to the pilot, the general to his men–Whitman details lovemaking by connecting it to other examples of trust and companionship between men. This opens up the privacy of the lovers’ tryst to a more general spectrum of respect and love, which in turn is fed back in to develop the lovers’ relationship.

Most touching of all, Whitman calls the body an “act-poem” wherein lovemaking is nature’s poetry, a harmony of two voices. The act is divine, blessed and not shameful. The “divine father” is the seed of many generations of great children, just as Adam is the root of all of mankind. In the conclusion of the poem, we are directed to celebrate the act of union and the children that it produces. While working to undo all the deep-seated religious and cultural taboos associated with sex, Whitman describes the act beautifully, praises its worth and creates from it a pure image of its divine origin and divine works.

September 22nd, 2009 § § permalink

Generation Y is very comfortable with its sense of individualism.

Nicknamed the ME, or millenium generation, each one of us has been taught to prize our own sense of self, often to the point of overindulgence. Whitman is also a subscriber to individualism, but his poetry takes the concept far from its modern selfish bent.

Each of us is, in a sense, our own universe, encompassing a whole galaxy of senses and institutions. Each world is unique, which means that each of us perceives everything around us differently. Our common world is fractured into billions of singular variations, attuned to each man or woman’s view and experiences.

Although this may sound abstract, Whitman explains this individualism concretely in the latter part of Leaves of Grass (1855.) Not only are our legislative laws and world religions secondary to the great immortality and power of man, but even the laws of gravity and physics are subject to him. Man is his own poem, and he holds a poetic power capable of god-like creation, as Whitman states, “leaves are not more shed out of trees or trees from the earth than they are shed out of you” (p.93.)

Without man, art, architecture, music, sculpture, would have no meaning. History, politics and even civilization is dependent on the individual, and like the early sketches of the celestial bodies rotating around the earth, all of these institutions revolve around the individual.

We are not put on the earth by chance, Whitman claims, and we are not subject to fate or the rise and fall of fortune. Divine powers do no exist to dwarf us or withdraw something essential from us at whim (92.) The very fact that we exist on earth is heavy with significance. Imagine a world with billions of souls, each capable of creating an entire universe to carry around with him through life and beyond death.

In the face of this great creative potential, in the powers we have with these universes in our pockets, the cohesiveness of the world seems to fall apart. How is it possible that man can connect to his fellow man if what we experience is so different from person to person? Would this not lead to certain isolation? The concept of the mad writer trapped in his own head is not an uncommon figure in literature. Is it still possible for us to get in touch with mankind?

Whitman assures us that these splinters of reality are drawn together with one look in the mirror:

Will the whole come back then?

Can we see the signs of the best by a look in the lookingglass? Is there nothing greater or more?

Does all sit there with you and here with me? (p. 94.)

One look in the mirror shows us the perfect combination of the universe of our thoughts and experiences–we are met with the image of our own face. Only we know the intricacies of the way we see the world, but everyone we meet is able to see our face: a highly condensed but nevertheless true symbol of our selves.

Although they were contemporaries, the writing of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and Walt Whitman could not be more different. Longfellow was by far the era’s most popular poet, a “fireside poet” whose poems for adults and children were popular with the masses. Whitman, the rabble rouser, wrote poetry for the masses, but was not quite as popular as Longfellow with the common man. Perhaps Longfellow’s charming rhymes, gentle cadence and mild, uncontroversial subject matter was better suited as recreation for the layman’s lifestyle. Whitman was beloved by his fans, attracting notice by British readers for his revolutionary work.

Although they were contemporaries, the writing of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and Walt Whitman could not be more different. Longfellow was by far the era’s most popular poet, a “fireside poet” whose poems for adults and children were popular with the masses. Whitman, the rabble rouser, wrote poetry for the masses, but was not quite as popular as Longfellow with the common man. Perhaps Longfellow’s charming rhymes, gentle cadence and mild, uncontroversial subject matter was better suited as recreation for the layman’s lifestyle. Whitman was beloved by his fans, attracting notice by British readers for his revolutionary work.