“For want of anything better, let me lightly twine a spring of the sweet ground-ivy trailing so plentifully through the dead leaves at my feet…and lay it as my contribution on the dead bard’s grave” (941).

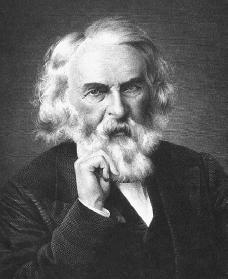

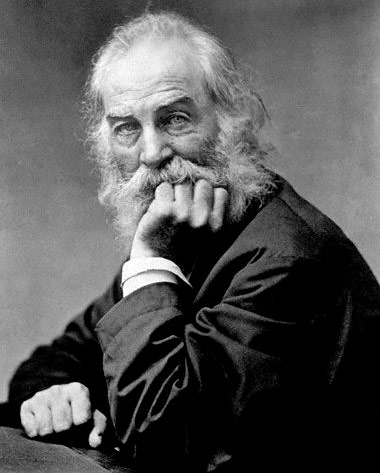

Although they were contemporaries, the writing of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and Walt Whitman could not be more different. Longfellow was by far the era’s most popular poet, a “fireside poet” whose poems for adults and children were popular with the masses. Whitman, the rabble rouser, wrote poetry for the masses, but was not quite as popular as Longfellow with the common man. Perhaps Longfellow’s charming rhymes, gentle cadence and mild, uncontroversial subject matter was better suited as recreation for the layman’s lifestyle. Whitman was beloved by his fans, attracting notice by British readers for his revolutionary work.

Although they were contemporaries, the writing of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and Walt Whitman could not be more different. Longfellow was by far the era’s most popular poet, a “fireside poet” whose poems for adults and children were popular with the masses. Whitman, the rabble rouser, wrote poetry for the masses, but was not quite as popular as Longfellow with the common man. Perhaps Longfellow’s charming rhymes, gentle cadence and mild, uncontroversial subject matter was better suited as recreation for the layman’s lifestyle. Whitman was beloved by his fans, attracting notice by British readers for his revolutionary work.

In Specimen Days on April 3rd, 1882, Whitman learns about the death of Longfellow through the newspaper and reminisces on the accomplishments of the fellow poet. His comments seem to weigh disapproval with plentiful praise, beginning with, “Longfellow in his voluminous works seems to me not only to be eminent in the style and forms of poetical expression that mark the present age, (an idiosyncrasy, almost a sickness, of verbal melody,) but to bring what is always dearest as poetry to the general human heart and taste” (941.) Whitman is not a fan of Longfellow’s insistent use of rhyme, the usage of which is not mere style, but a sickness, a dependance on formal verse. Poetry that reads like a song is suited to the common man’s taste, but this appears to be a degradation rather than an enhancement of the form. Longfellow adapts poetry to be readable by a large audience, simplifying it and its art for the general populace.

Yet Whitman goes on to claim that Longfellow represents “the sort of bard and counteractant most needed for our materialistic, self-assertive, money-worshipping Ango-Saxon races, and especially for the present age in America–an age tyrannically regulated with reference to the manufacturer, the merchant, the financier, the politician and the day workman–for whom and among whom he comes as the poet of melody, courtesy, deference” (942). Longfellow is the one poet to take the gift of poetry beyond the literary minded and share its music and its power with the everyday workman. In this way, Longfellow democracizes poetry, making it accessible to all those who are able to read. Poetry now has its place beside storytelling and biblical texts as one of America’s most popular literary pastimes.

Longfellow is the “universal poet of women and young people”–a poet of sentimentality (942). Whitman defends Longfellow from his critics who claim that the poet’s lack of originality. Originality is dependent on the exploration and study of the literary figures and works of the past. Before America, the New World, “can be worthily original, and announce herself and her own heroes, she must be well saturated with the originality of others, and respectfully consider the heroes that lived before Agamemnon” (943).